The notion is that if Australia simply relaxed planning restrictions and let developers build apartments wherever they wanted, then Australia’s housing crisis would magically resolve.

This myth has been demolished by an article in the Daily Telegraph, which reports that “Almost one billion worth of housing in one of Sydney’s most affordable local government areas is yet to be built despite the DAs being approved up to five years ago”:

“The dead zones – also known as “zombie DAs” are located in Liverpool – one of the most affordable local government areas in Sydney”.

“Each has been approved for a residential flat development, including one for a 25-storey complex worth more than $40 million that was lodged in 2016”.

“The DAs represent potential homes for an estimated 1600 families, but are yet to be activated with construction and labour costs, rising interest rates and government taxes blamed for the delays”…

Liverpool Mayor Ned Mannoun said it was taking between five to seven years from DA approval to a “key in the door”.

The New Daily’s Michael Pascoe also debunked the myth that simply relaxing planning would lead to a swathe of new homes being built:

“Before a council can approve an application, the application has to be made. Turns out applications and approvals are pretty much in balance – proportionately very few are rejected and there are generally more approvals than dwellings proceeding”.

“It also turns out there actually is a large stock of potential housing already approved, but those planning approvals are being sat on by developers awaiting the most profitable moment to start building”.

Pascoe sited a specific example from Victoria to prove his point:

“In the first half of this financial year, 19,231 planning permit applications were received, 2569 were withdrawn or lapsed and only 532 were refused”.

“Not only is the planning/approval process not to blame for the shortage of dwellings, it is running ahead of developers willing and/or able to build”.

Tens of thousands of home approvals in Australia are withering on the vine because it is not viable for builders to proceed.

Therefore, just eliminating planning constraints, as is currently advocated, will not magically alleviate the “supply” problem.

We should also understand that flooding the housing market with fresh supply is not in the developers’ best interests because it reduces their profitability.

Developers would be better off financially drip-feeding supply to keep prices high and increase their margins.

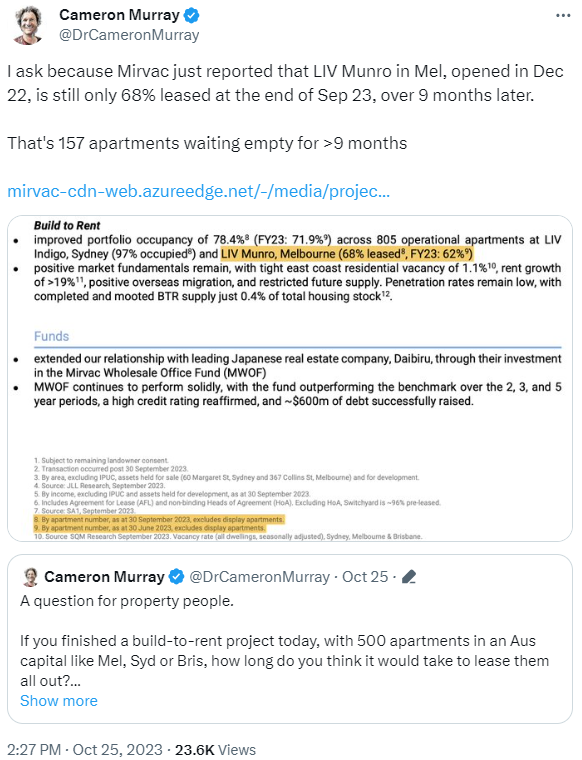

For example, Mirvac left 157 unoccupied units at its LIV Munro development in Melbourne for nine months during the worst rental crisis in history:

Developers profit handsomely from perpetuating the housing shortage, and this will not change unless our governments decide to regulate land release to force development and sale.

Short of forcing developers to provide housing, the only assured option to expand housing supply is for governments to create new housing stock directly through public housing programs. But doing so is very expensive.

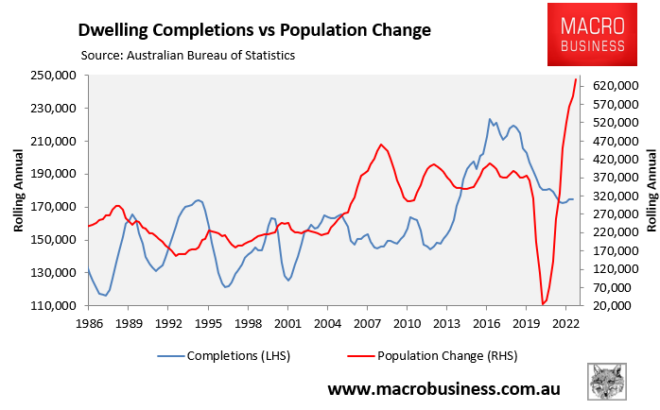

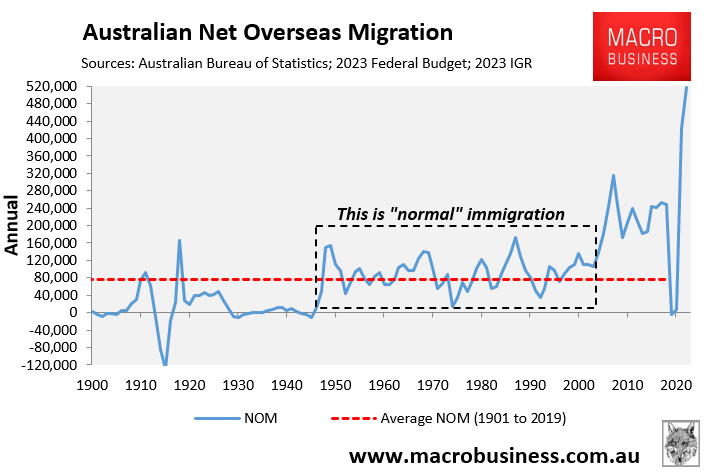

A lower cost, faster and more sustainable solution is to lower net overseas migration to historical levels of below 120,000 a year:

If we truly want to solve the nation’s housing shortage, net overseas migration must be lowered to a level below the nation’s capacity to create both housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, population demand will continue to exceed supply, and the housing “supply crisis” will persist.