It is not me saying this. It is Westpac’s Luci Ellis, former Head of Financial Stability and Assistant Governor of Economics at the RBA.

First, core inflation measures have not fallen anywhere near as much as headline measures in most countries. Headline series are being flattered by the unwind of the previous surges in food and energy prices. Once those price falls wash out, headline inflation will converge on core rates. Depending on the pace of decline of core inflation, headline inflation could therefore pick up temporarily in some economies.

Australia is in a different situation. Because of the way our electricity market is regulated and priced, the main effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Australian retail electricity prices did not occur until the second half of 2023. The rise in businesses’ power costs has also been drawn out as supply contracts roll over. By contrast, in many countries the effect was already unwinding by then and dragging headline inflation down. This more drawn-out inflation dynamic is one of the reasons why headline inflation in Australia is still outpacing its peers.

…Australia saw a larger peak contribution from goods inflation – almost 4 percentage points – than the other peer economies. At first glance this might have been interpreted as implying that Australia had a larger imbalance of supply versus demand than its peers. However, a deeper look shows this is not the case in general.

At its peak in mid-2022, nearly 2 percentage points of the contribution of goods inflation to total annual inflation was accounted for by one component – home-building costs. Part of this was because supply chain issues affected building materials as well as other commodities. Prices of many building materials are still rising in Australia, even though comparable data for some other countries are showing declines.

But there is more to it than this. ABS data on output prices for residential construction have been rising a bit faster than building materials costs in recent quarters. The price rises therefore can’t all be the passing on of recent increases in materials costs. Some of the difference might be labour costs, including from weather-related stoppages or more generalised poor productivity. Margins are presumably being rebuilt as well. This is understandable given that many builders were squeezed when rising costs collided with existing fixed-price contracts, with some becoming insolvent or otherwise leaving the industry.

Most countries do not include home-building costs in their CPI measure, but Canada does. It is a useful comparator given it, too, has seen strong population growth and rising housing prices. Population growth has been even stronger there than in Australia, exceeding 3% over 2023. The surge in rent inflation in Canada has been similar to that in Australia, peaking at around 8%.

Like Australia, Canada also saw a surge in building costs, but this peaked around the middle of 2022. Since then, the home-building component of the CPI has been declining slightly; it is now 2% below its peak. In contrast, home-building costs as measured in the Australian CPI have increased by around 7% over the same period. This is a significant gap to open up over a relatively short horizon.

That is, the Albanese government’s failure to act to protect Australia from the gas cartel cost us 18 months of energy shock.

Moreover, its mad immigration deluge inflated rents and building costs by sucking resources into infrastructure over housing. The energy shock is also severe in building materials.

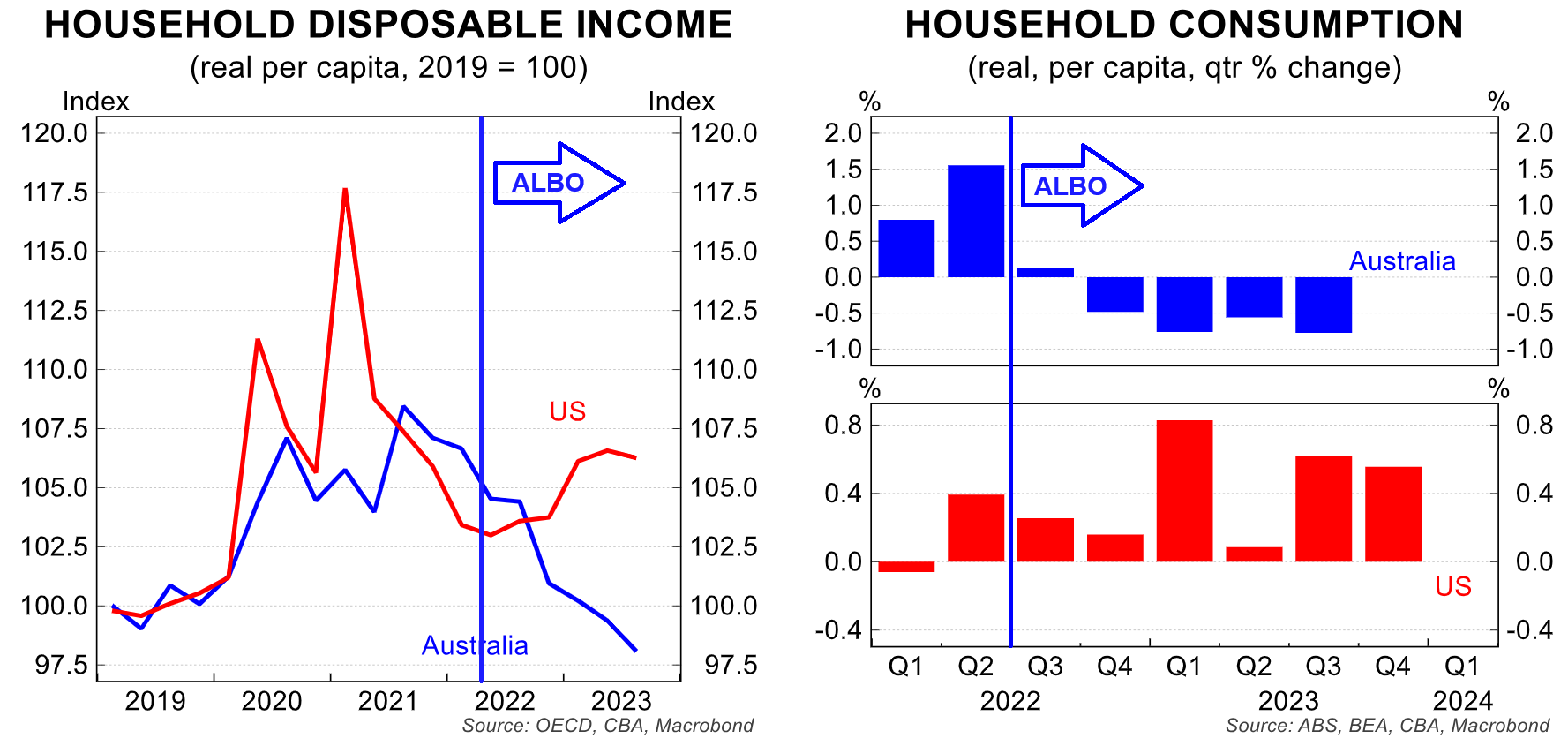

That’s what Westpac means by “homegrown inflation”. Grown by Albo blundering and costing Aussies dearly the moment the ALP came to power: