Bad loans are everywhere:

China is embarking on its biggest consolidation in the banking industry by merging hundreds of rural lenders into regional behemoths amid growing signs of financial stress.

After engineering mergers of rural cooperatives and rural commercial banks in at least seven provinces since 2022, policymakers pinpointed tackling risks at the $6.7 trillion sector as one of its top priorities for this year. That means another wave of consolidation is on the way across the nation.

China’s banking industry has been weighed down by a litany of troubles over the past years, including a deepening slump in the real estate market and an overall fragile economy. The 2,100 banks in the rural cooperative system saw their bad-loan ratio stand at 3.48% at the end of 2022, more than twice as high as that for the whole sector.

It’s going to get worse, thanks to bad policy. TSLombard:

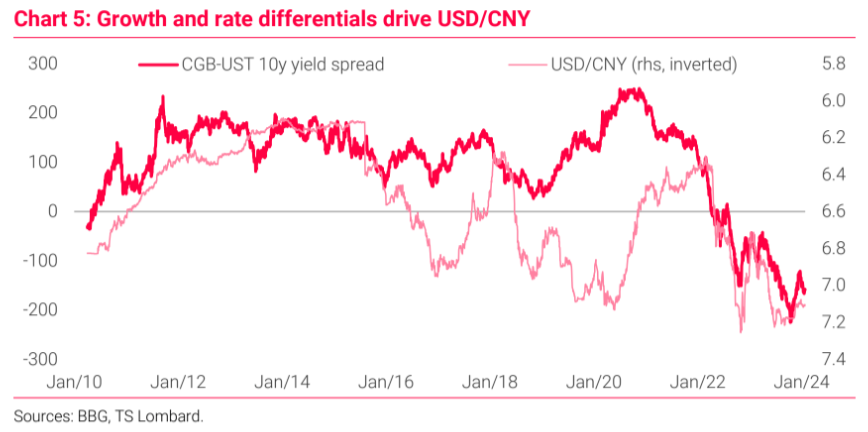

An emerging ‘rich RMB’ policy? In September last yearwe noted signs of change in PBoC FX management as the bank in effect drew a line in the sand at USD/CNY 7.32.

This had a clear short term goal of boosting market and macro confidence. However, since then, Xi Jinping has talked about developing China into a “financial power”: of the six prerequisites identified to achieve this goal, a “strong currency” is placed first.

The CCP, as we noted in 2022, is pushing to build financial as well as technological resilience. Accordingly, Governor Pan Gongsheng has raised the importance of “currency stability”–both domestic price and foreign exchange–in recent comments.

Pan gave a positive spin on the implications for PBoC easing, noting that onshore prices and the prospect of Fed cuts provided a rationale and room for more monetary action.

And it is noteworthy that theauthorities sought the repatriation of offshore funds–a move to strengthen RMB–when responding to recent market turmoil.

Needless to say, an artificially strong currency attached to a weak economy is not a good combination.

There is clear logic to preventing rapid and uncontrolled depreciation. The USD/CNY rate is a closely watched barometer of economic health and has a significant impact on business confidence and capital flows.

Nevertheless, a sustained period of suppressing domestic consumption or engaging in tighter monetary policy–the latter being the more likely–to prevent the yuan weakening would risk further harming already sluggish spending, loan growth and monetary velocity.

The PBoC will increase stimulus this year, largely through structural lending programmes such as PSL.

In China, the cost of money is less important than the quantity, especially in the current environment with demand for loans so weak.

But even so, higher short-term financing costs will add to the squeeze.

The pain will be felt in net interest margins, particularly for beleaguered small banks that rely on interbank markets for funding.

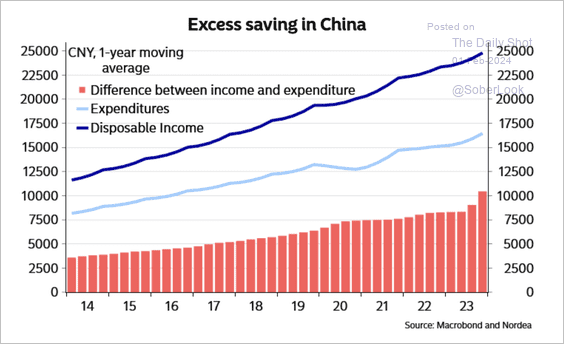

None of this makes much sense. Households are shocked by a balance sheet recession owing to falling real estate prices.

Instead of aiding their deleveraging, you keep real rates artificially high and boost activity with more real estate to ensure ongoing price falls? To wit:

A state-backed property project in China has received the first development loan under a so-called whitelist mechanism and two more major cities have eased home-buying curbs, state media reported, as concerns mount about the liquidation of Evergrande.

Additionally, China Development Bank and Agricultural Development Bank of China will provide credit lines worth 142.6 billion yuan to fund the renovation of “urban villages” in the southern city of Guangzhou, the city government said.

The result speaks for itself:

Beijing is embedding debt deflation.