The latest OECD figures show how Australian living standards have collapsed since the Global Financial Crisis hit in 2008.

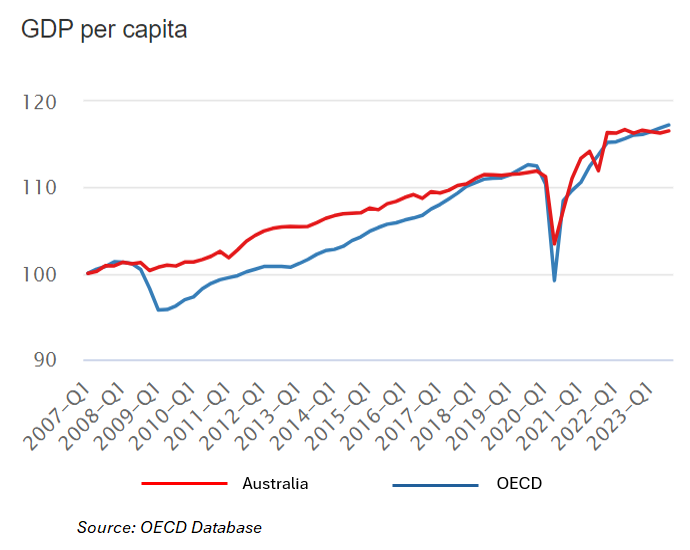

The next chart shows that Australia’s GDP per capita has grown more slowly than the OECD since Q1 2007.

Australia’s GDP per capita grew by 16.6% between 2007 and 2023, versus 17.3% across the OECD average:

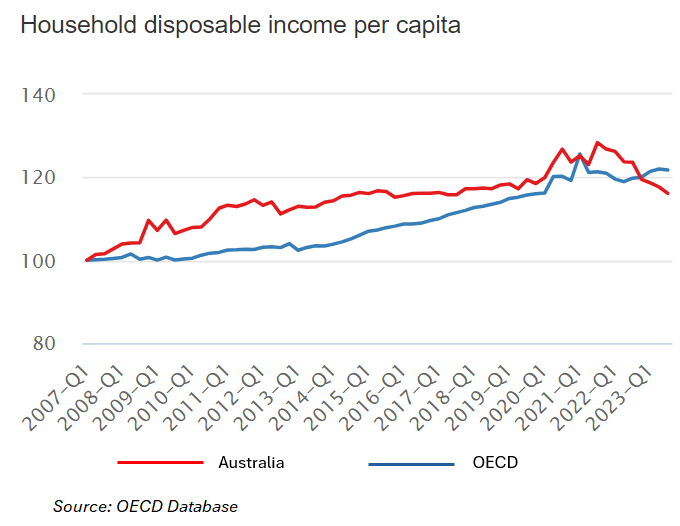

The situation is far worse when it comes to real household disposable income per capita, which is the leading indicator of material living standards.

Australia’s real per capita household disposable income has increased by only 16.1% since Q1 2007, versus 21.8% growth across the OECD average:

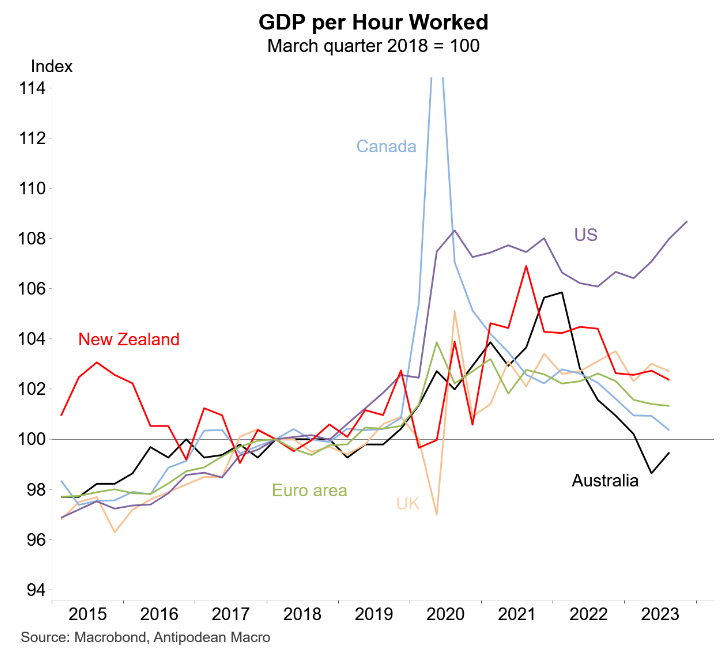

Separate data published recently by Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro showed that Australia has also recorded the worst labour productivity over the past decade:

Australia’s labour productivity has grown at a near-zero rate since 2015, while productivity leader, the United States, has recorded labour productivity growth of around 13% over the same time period.

There are several factors explaining Australia’s poor labour productivity and declining living standards.

First, Australia’s population has ballooned by 8.1 million people (43%) this century alone thanks to high immigration.

However, business investment, infrastructure investment, and housing have failed to keep pace.

This has driven Australia’s capital stock per worker through the floor, resulting in “capital shallowing” and lower productivity growth.

Congestion costs have also risen because infrastructure has become overburdened, further restricting output.

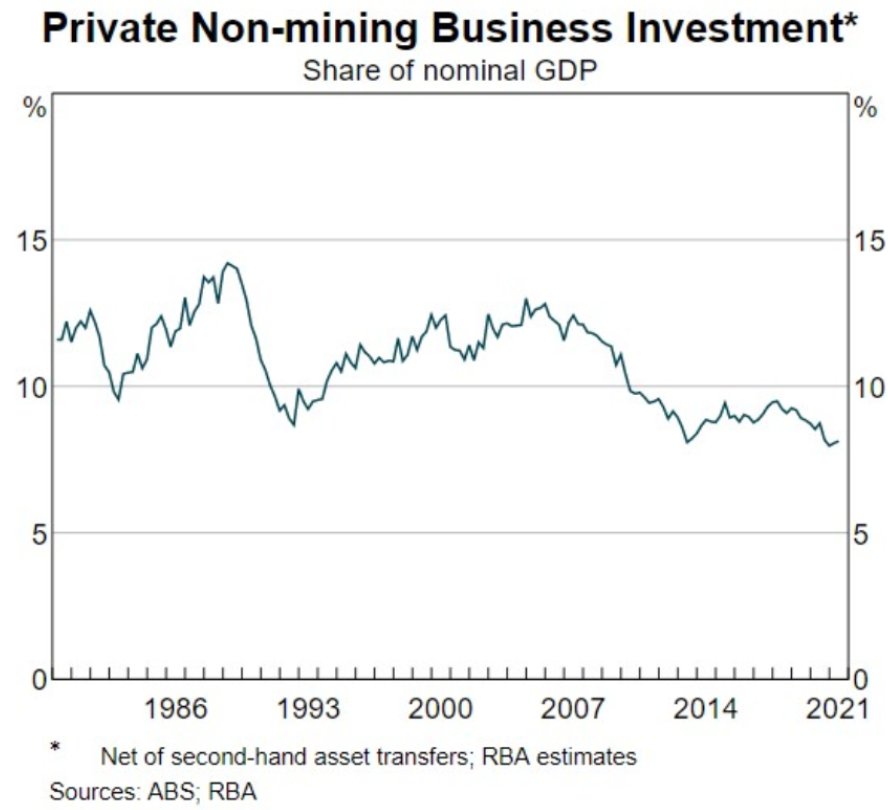

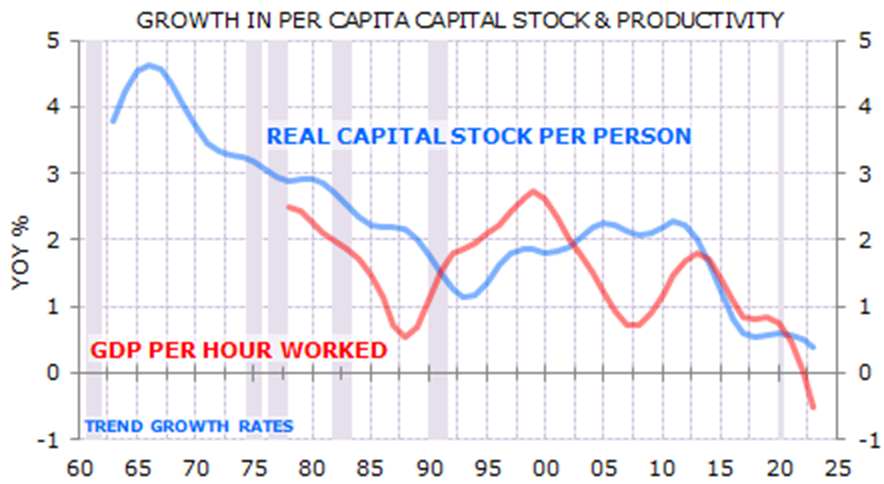

Australia’s “capital shallowing” was stunningly illustrated in the next chart from independent economist Gerard Minack:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, Minack wrote in his November report.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, Minack warned.

The growing labour supply from high net overseas migration suppresses wages, incentivising businesses to delay investing in labour-saving technologies and automation, which lowers productivity.

After all, why bother investing in productivity savings when you can hire cheaper migrant labour instead?

Mass immigration also diverts the nation’s resources toward low-productivity “people-servicing” businesses, as well as directs the nation’s productive effort towards building infrastructure and housing, rather than capital deepening.

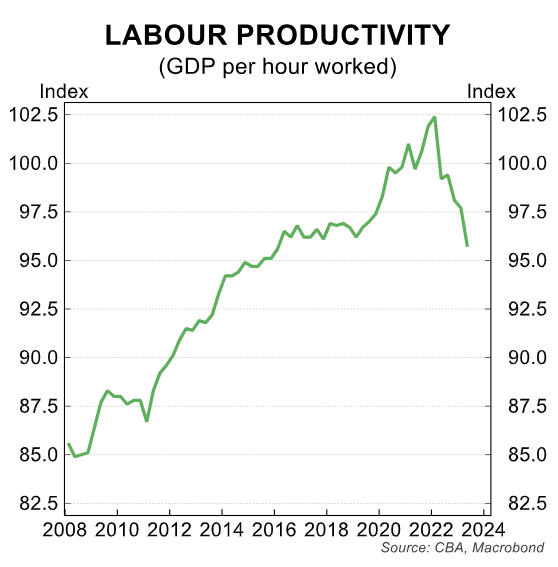

It is no coincidence that Australia’s labour productivity growth surged when net overseas migration turned negative during the pandemic:

This is because Australia experienced a phase of “capital deepening” in which the nation’s capital stock was distributed among fewer people, which increased productivity.

But as soon as net overseas migration rebounded to an all-time high, the nation’s productivity growth plunged because of “capital shallowing” as the nation’s capital stock was shared among more people.

Finally, Australia is unique in that it pays its way in the world primarily through the sale of its fixed mineral endowment.

Importing huge volumes of people through immigration distributes these mineral riches among more people, resulting in reduced wealth per person.

The Albanese Government’s record immigration will exactly the same results as illustrated above.

Australia’s productivity and per capita GDP will stagnate, as will wage/income growth.

Overall livability will also continue to degrade as infrastructure, housing, and the natural environment are crush-loaded.