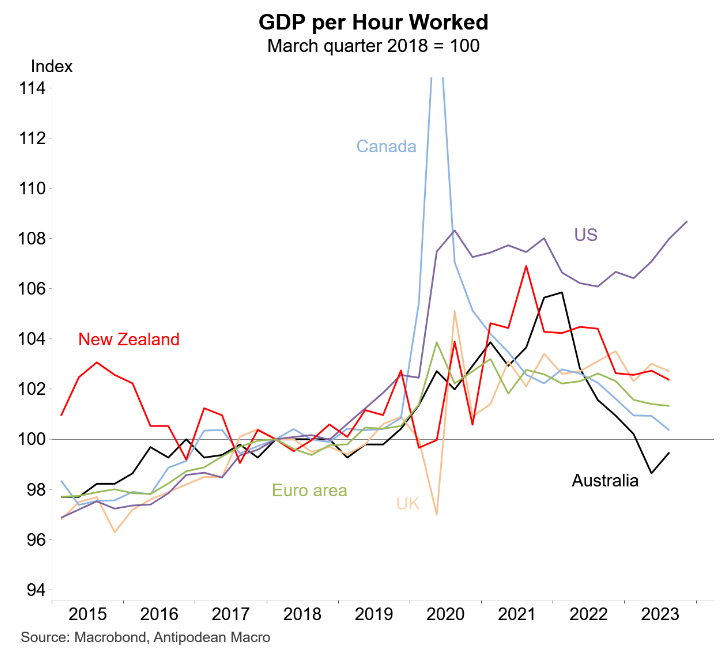

Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro published the below chart showing that Australia has recorded the lowest labour productivity growth among advanced nations, ahead of second worst Canada:

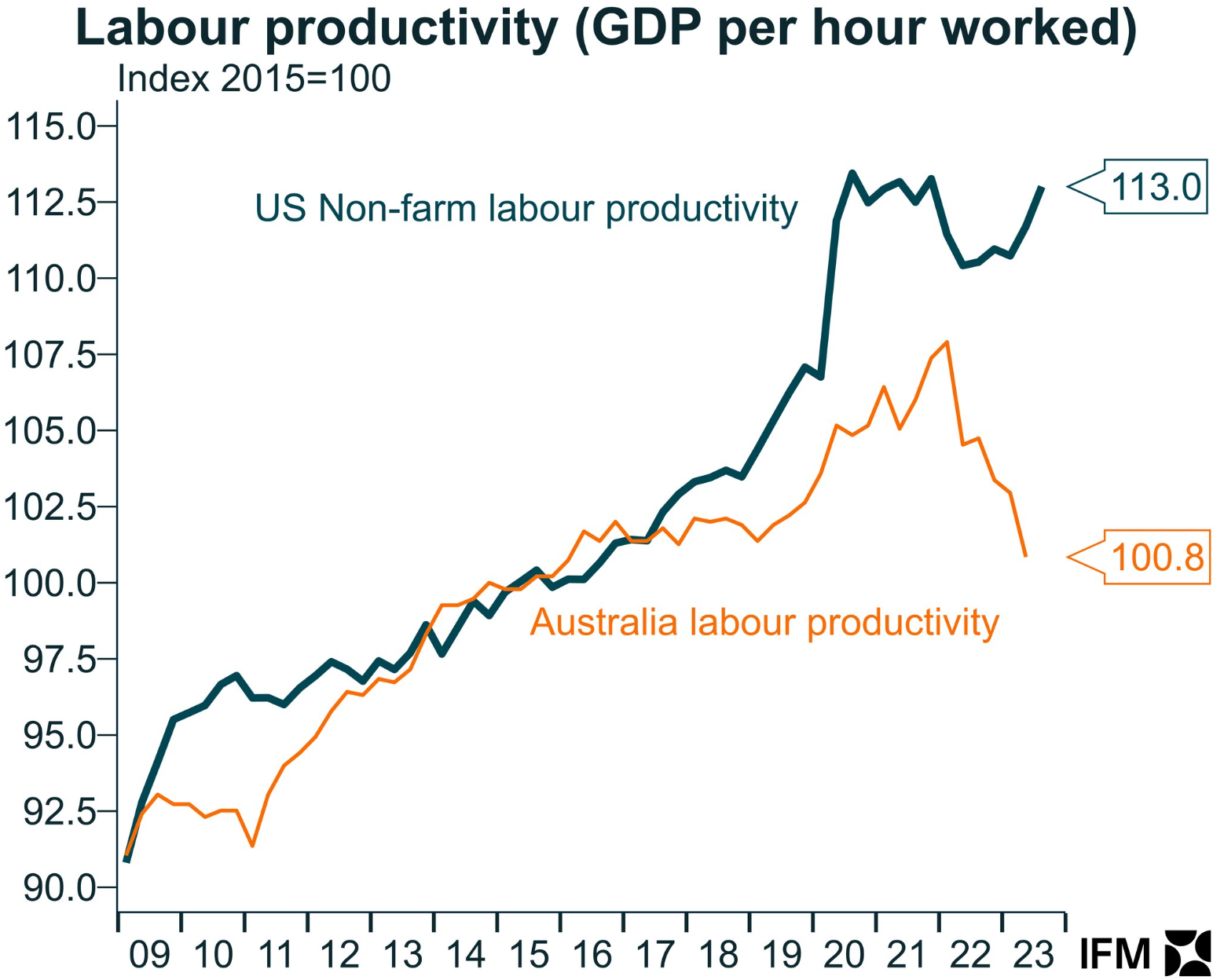

The divergence between Australia and the United States is especially stark, as illustrated in the below chart produced last year by Alex Joiner at IFM investors:

As you can see, Australia’s labour productivity has grown at a near-zero rate since 2015, while the United States’ labour productivity has increased by 13% during the same time period.

There are several factors contributing to Australia’s low labour productivity.

First, high net overseas migration has increased Australia’s population by 8.1 million people (43%) this century alone.

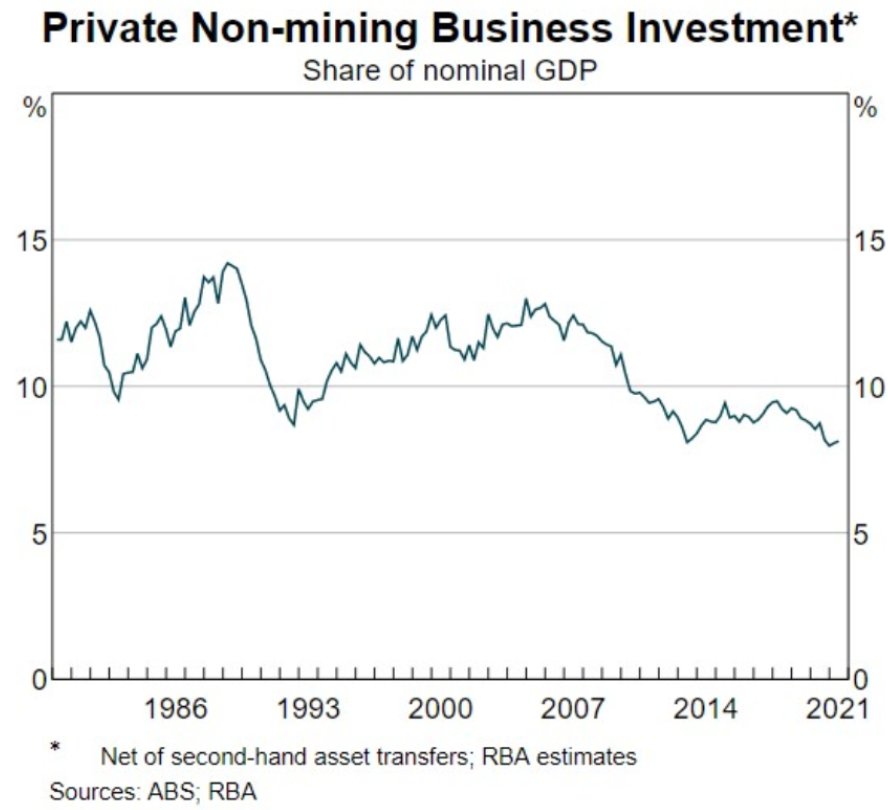

However, business investment, infrastructure investment, and housing have not kept up.

As a result, capital stock per worker has decreased, leading to “capital shallowing” and reduced productivity.

Congestion costs have also increased as infrastructure has been overburdened, further limiting output.

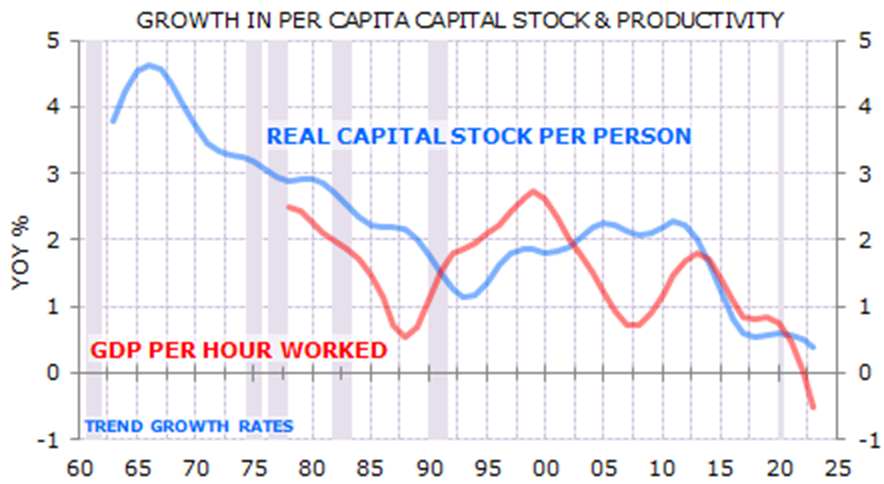

This “capital shallowing” was stunningly illustrated in the below chart by independent economist Gerard Minack in his November report:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, Minack wrote.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, Minack warned.

Migrants in Australia earn less than the median pay and are more likely to be unemployed than the general population.

The increased labour supply caused by high immigration drives down wages, causing businesses to avoid investing in labor-saving technologies and automation, lowering productivity.

After all, why invest in productivity savings when you can hire cheaper labour?

Large-scale immigration also diverts resources, encouraging the creation of low-productivity “people-servicing” businesses while directing the nation’s productive effort towards infrastructure and housing.

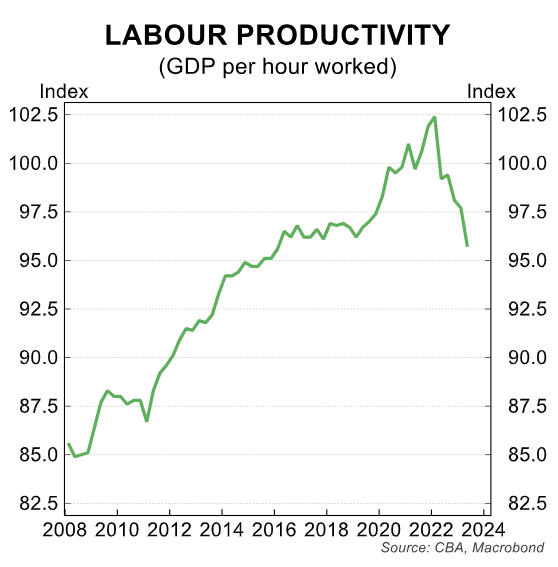

Interestingly, Australia’s labour productivity growth soared when Australia’s net overseas migration turned negative during the pandemic:

Australia experienced a phase of “capital deepening” in which the nation’s capital stock was distributed among fewer people, increasing productivity.

However, once net overseas migration rebounded to an all-time high, productivity growth plummeted due to “capital shallowing” as the nation’s capital stock was divided over more people.

Finally, Australia is unique in that it pays its way in the world mostly through the sale of its fixed mineral reserves.

Importing a huge number of people through immigration distributes these mineral riches among more individuals, resulting in reduced wealth per person.

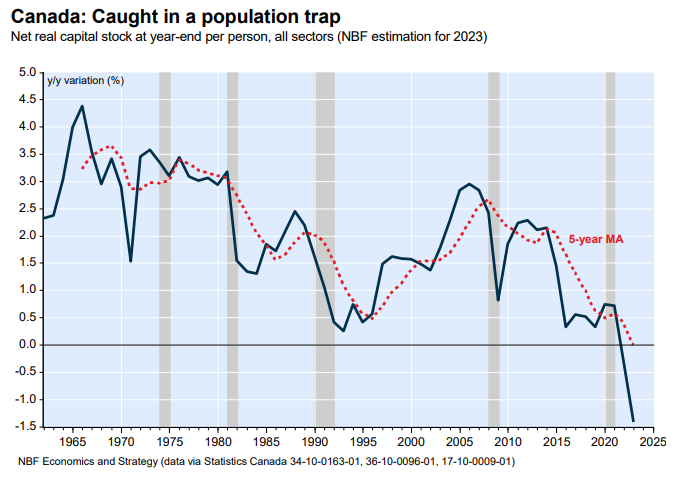

It is no mistake that Canada runs the same growth model and is experiencing the same problems of capital shallowing, low productivity growth, falling real per capita GDP, and an acute rental crisis.

The Albanese Government’s record immigration policy will achieve similar results to last decade.

Productivity and per capita GDP growth will stagnate, as will wage/income growth.

Overall livability will also continue to fall as housing, infrastructure, and the natural environment are crush-loaded.