The Productivity Commission (PC) released its quarterly Bulletin, which notes that the “productivity bubble” associated with the pandemic has well and truly passed.

Below are the key extracts in italics.

Changes in productivity through the COVID-19 pandemic were largely attributable to temporary shifts in where people were employed:

Australia experienced a ‘productivity bubble’ during the COVID-19 pandemic (figure 1).

The sharp productivity rise (and subsequent sharp decline) is unlikely to reflect workers becoming more (or less) productive – instead, the pandemic led to major (but temporary) shifts in where people were employed – away from relatively low productivity sectors, towards high productivity sectors.

Labour productivity rose sharply in March 2020 as relatively low productivity sectors shed workers, increasing the average productivity of the workforce even as the economy slowed (PC 2023b, p. 5).

As pandemic-related restrictions were eased, and workers moved back to lower productivity sectors, predominantly in the services space, this trend reversed and average labour productivity declined.

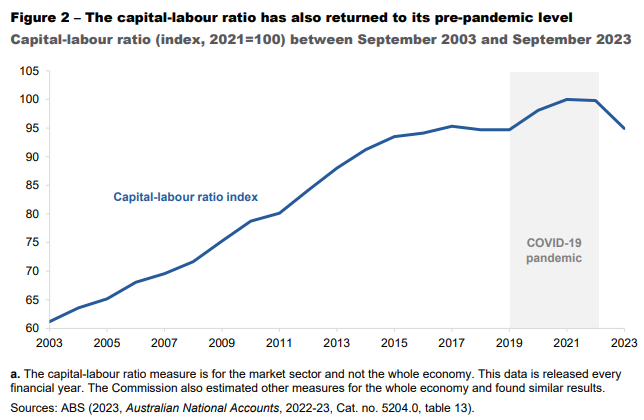

And increases to the capital-labour ratio were also short-lived:

Similar to the productivity bubble, the capital-labour ratio, or capital deepening – a key input into labour productivity – rose sharply during COVID-19. And as with the productivity bubble, this increase proved to be short-lived (figure 2)…

Some of the biggest increases in the capital-labour ratio occurred in the accommodation and food services, transport, postal and warehousing and arts and recreation services – all industries that shed high numbers of workers during the pandemic, and all have returned to about their pre-pandemic capital-labour ratios…

And the long-run trend is still a cause for concern:

Australia’s labour productivity returning to 2019 levels is still a concern. It means that the weak productivity growth (both labour and multifactor) experienced before COVID-19 has continued as Australia recovered from the pandemic.

In the decade leading to 2019 multifactor productivity growth (0.5%) was a little over half the average of the three decades prior (0.9%) (ABS 2023c). This reflects the combination of a global slowdown in productivity growth that has been ongoing since about 2005 (PC 2020).

As usual, the PC has conveniently failed to mention the roll of extreme immigration-driven population growth since 2005 in lowering Australia’s productivity.

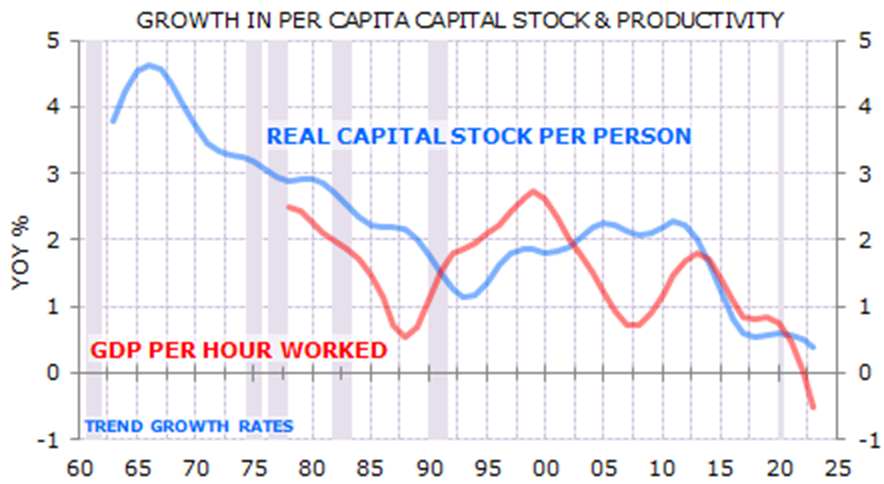

The below chart by economist Gerard Minack shows that Australia has experienced significant capital shallowing due to the inability of infrastructure, housing, and business investment to keep pace with the nation’s bulging population:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, wrote Minack.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable”.

“There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, warned Minack.

Minack’s assessment mirrored many of the arguments that I have put forward regarding the productivity-lowering aspects of Australia’s mass immigration policy.

AMP chief economist, Shane Oliver, made similar arguments in August when he noted that “very strong population growth with an inadequate infrastructure and housing supply response has led to urban congestion and poor housing affordability which contribute to poor productivity growth”.

AFR economics editor, John Kehoe, also cautioned in November that “business start-ups are declining among younger generations and rocketing property prices may be to blame”, which is hampering Australia’s productivity performance.

“The high cost of residential property may be impeding entrepreneurship in at least two ways”, argued Kehoe.

“First, because land has become so expensive (to both buy and rent), this makes it harder for people to take time off a regular job and take the risk of starting a new business venture”.

“Second, RBA research suggests that high house prices relative to incomes make it harder for young entrepreneurs to access business finance”.

Kehoe warned that less entrepreneurialism is bad for the economy and productivity because “new business start-ups are disruptors, innovators and competitors”, they “knock out old cossetted incumbent businesses and introduce new products to the market”, and put “downward pressure on prices”.

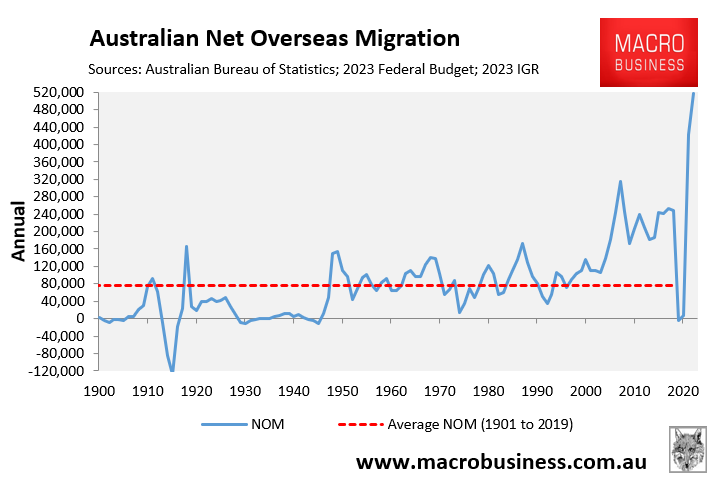

Obviously, one of the key drivers of the nation’s expensive housing is historically high levels of net overseas migration, which has overwhelmed supply.

Luci Ellis, chief economist at Westpac, argued that the recent decline in Australia’s productivity performance could be explained by a surge in low-wage jobs:

“People have not individually become less productive; there are simply relatively more low-paying jobs than before, which account for less GDP per hour”, she said.

“If true, this is a level shift effect and should not have a lasting effect on growth in productivity”.

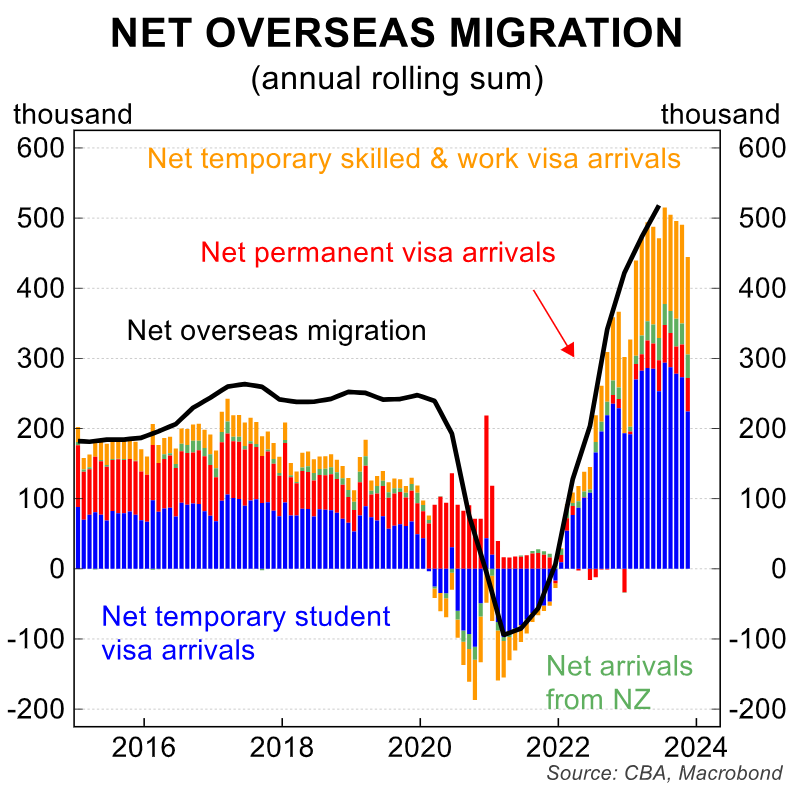

The rush of international students into Australia, the majority of whom work in low-wage jobs, is clearly driving the dramatic increase in said jobs:

When Australia’s net overseas migration and student numbers fell during the pandemic, labour productivity surged.

Australia experienced the period of “capital deepening” shown by the PC above, in which the nation’s capital stock was dispersed over fewer people, increasing productivity.

However, now that net overseas migration is at historic highs, productivity growth has slowed due to “capital shallowing” as the nation’s capital stock has been divided across more people.

Migrants to Australia earn less than the national median.

Rapidly increasing labour supply via mass immigration puts downward pressure on wages, causing businesses to avoid investing in labor-saving technologies and automation, lowering productivity.

After all, why invest in productivity improvements when you can hire low-cost migrant workers instead?

Large-scale immigration also diverts resources, promoting growth in low-productivity “people-servicing” industries while directing the nation’s productive effort towards infrastructure and housing.

Policymakers and economists need to abandon the notion that mass immigration increases productivity and living standards.

Because empirical evidence from 20 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration demonstrates the inverse.