KPMG chief economist Brendan Rynne has urged against a “short-sighted”, “kneejerk” cut to immigration in an attempt to address Australia’s housing problems, saying its research shows that skilled migrants help provide a positive boost to the economy by increasing productivity.

Rynne claims that if Australia turns away skilled migrants at this time, there is a risk they won’t come back later on.

“We’ve got to be careful that we don’t have a knee-jerk reaction”, he said.

“The work we’ve done has consistently shown that skilled migration adds positively to the Australian economy and it does that through improvements in productivity”.

“I’d actually live with the short-term challenges that we’ve got at the moment. I think ultimately the market will sort themselves out with regards to housing investment and then I’d rather do that than turn away skilled migration who are unlikely to come back later on”.

“If we start to pare back on skilled migration then the likelihood is that down the track we won’t achieve the same productivity kicker that we need and then ultimately we won’t get the real wage growth that we want to see”, Rynne said.

There is zero empirical evidence to back-up Rynne’s claims.

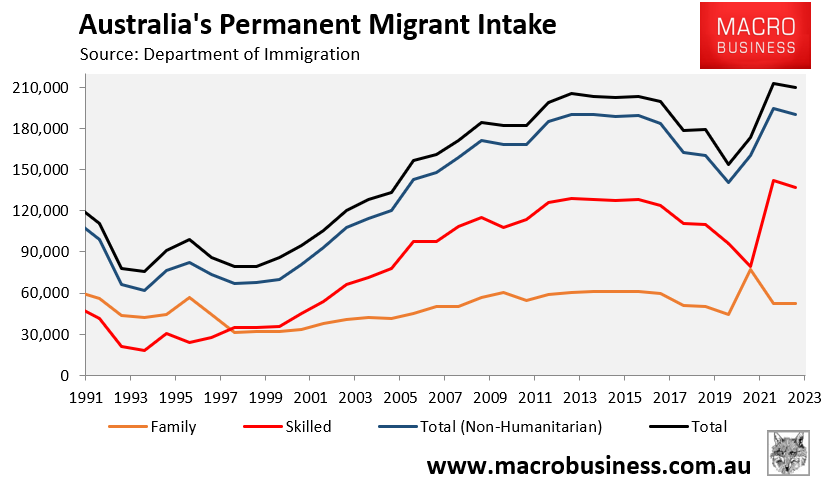

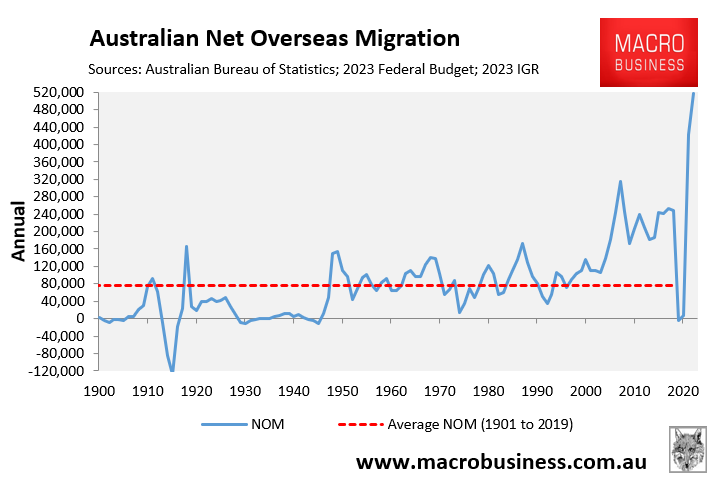

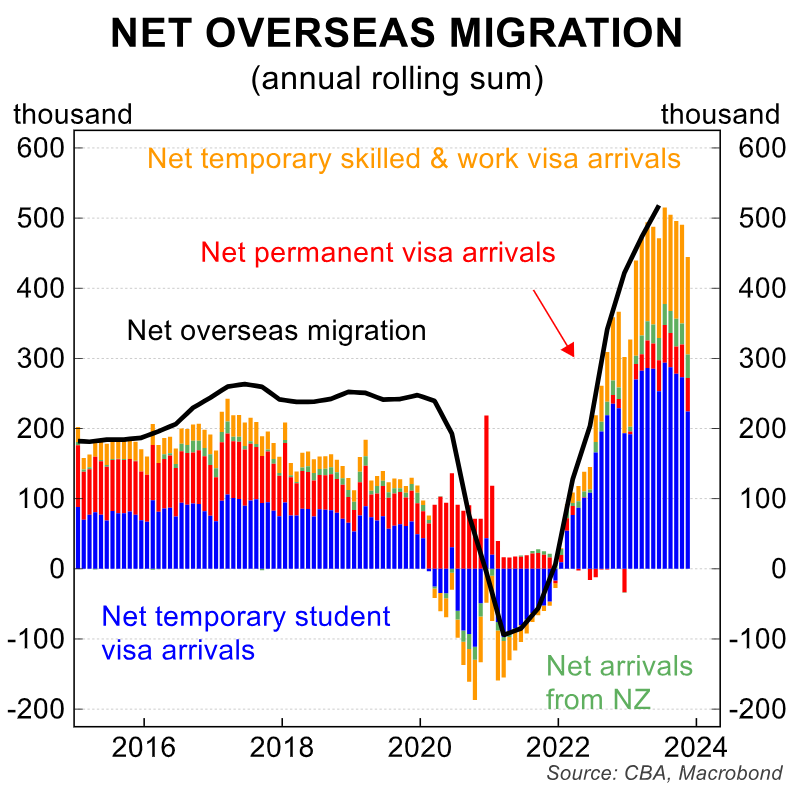

Australia massively ramped-up its ‘skilled’ migration program in the early 2000s, which was followed by the biggest explosion in net overseas migration (NOM) in Australia’s history:

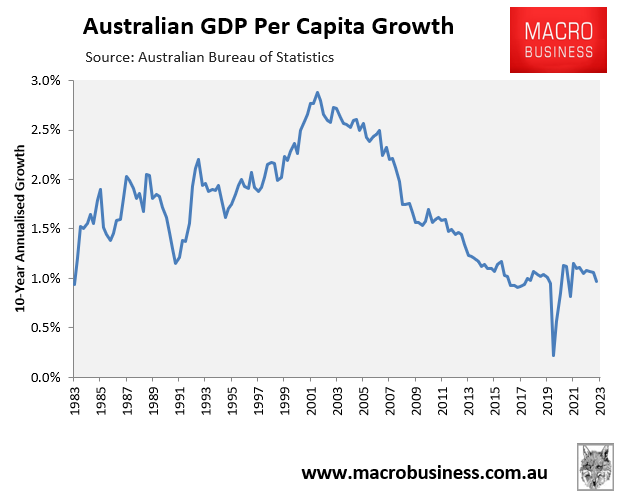

Australia’s productivity and per capita GDP per capita growth subsequently collapsed, which is the opposite of what should have occurred in Rynne fairytale world.

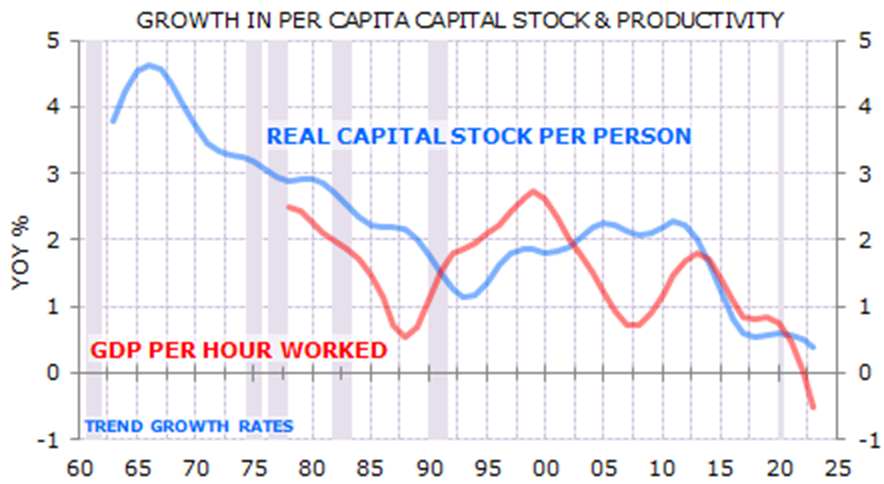

The reason why is obvious to any honest economist (which sadly there are few). The millions of migrants that piled into Australia diluted the nation’s stock of capital, leading to ‘capital shallowing’ and reduced productivity.

The below chart by economist Gerard Minack shows that Australia has experienced significant capital shallowing due to the inability of infrastructure, housing, and business investment to keep pace with the nation’s bulging population:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, wrote Minack in November.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable”.

“There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, warned Minack.

Many of the purportedly ‘skilled’ migrants come to Australia via the student visa route:

Yet, outcomes regarding international student graduates are abysmal with them dominating Australia’s working poor.

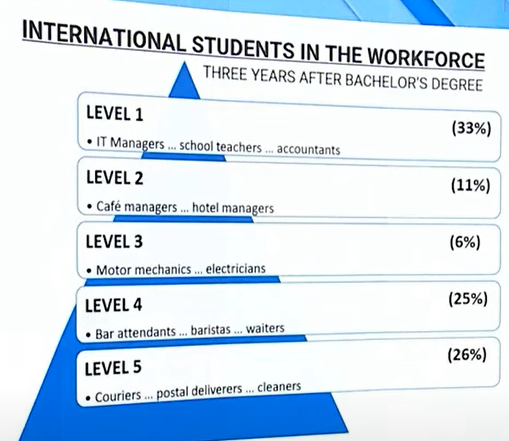

Just over half (51%) of international student graduates with a bachelor’s degree still in Australia after three years are working in low-skilled Level 4 or 5 jobs:

Delivering so many international graduates working in low-skilled and low-paid jobs is clearly one of the drivers of Australia’s low productivity.

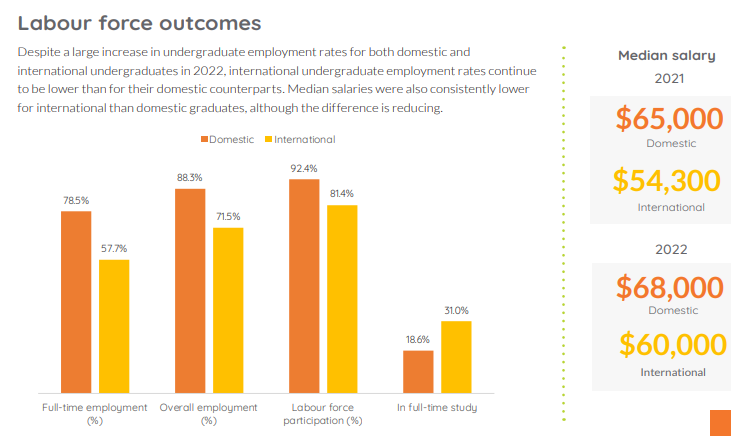

These findings are supported by the latest Graduate Outcomes Survey (GOS), which showed that international graduate employment rates, participation rates and median salaries are well below those of domestic graduates:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

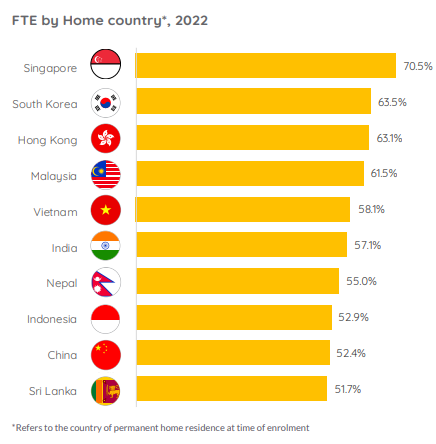

Disturbingly, Australia’s three largest source nations for international students – China, India and Nepal – each have poor labour market outcomes as measured by full-time employment:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

It’s little wonder that Australia is suffering both low productivity and persistent skills shortages if this is what the migration system is spewing out.

Australia’s edu-migration racket has literally delivered a giant low-paid, low-skilled migrant underclass.

This takes me to Rynne’s other bogus claim: that pairing back migration would harm “the real wage growth that we want to see”.

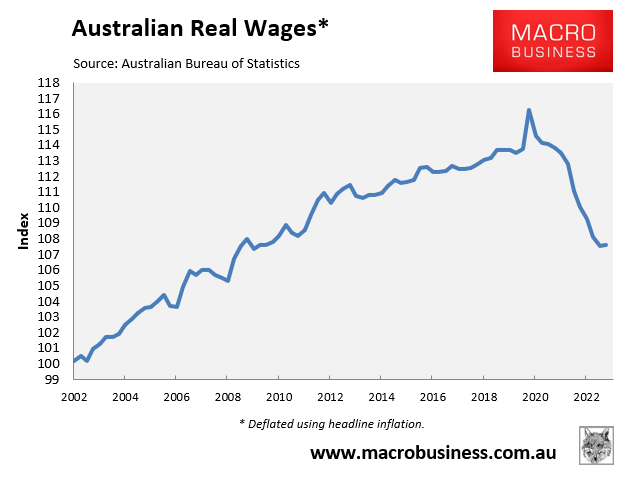

Over the past 20-year mass immigration period, Australia’s real wage growth has been abysmal:

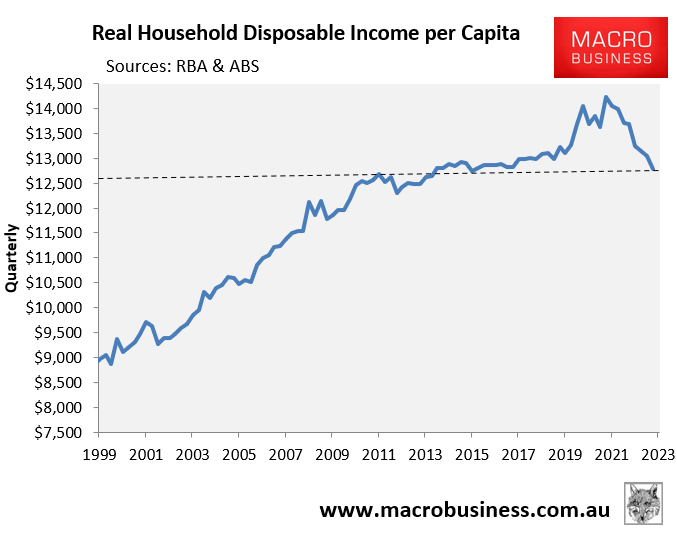

Australia’s real household disposable income per capita has also been abysmal:

Rapidly growing the labour supply via mass immigration puts downward pressure on wages, causing businesses to avoid investing in labor-saving technologies and automation, which lowers productivity.

After all, why invest in productivity improvements when you can hire low-cost migrant workers instead?

Large-scale immigration also diverts resources, promoting growth in low-productivity “people-servicing” industries while directing the nation’s productive effort towards infrastructure and housing.

Captured consulting economists like Brendan Rynne need to abandon the bogus notion that running a mass immigration policy lifts productivity and living standards.

Because empirical evidence from 20 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration unambiguously shows the inverse.