It is prediction time for MacroBusiness on what the economy has in stall for Australian households in 2024.

Household finances will remain under pressure:

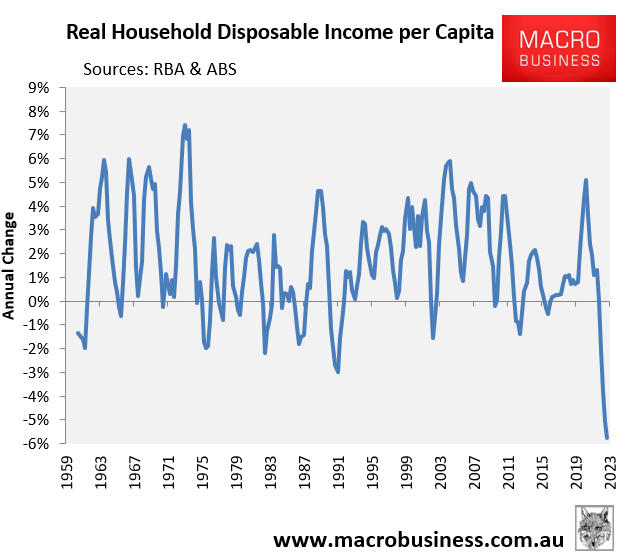

2023 was an unmitigated disaster for Australian households, who suffered the largest fall in real household disposable income on record:

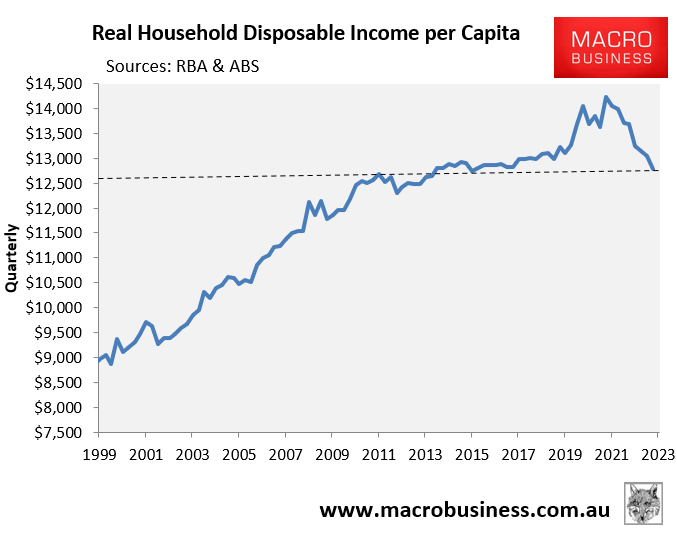

This circa 6% decline in real per capita disposable income took household incomes back to around 2011 levels, effectively wiping out 12 years of progress:

I expect near zero growth in real per capita disposable incomes in 2024 as wage growth softens alongside inflation, and unemployment rises.

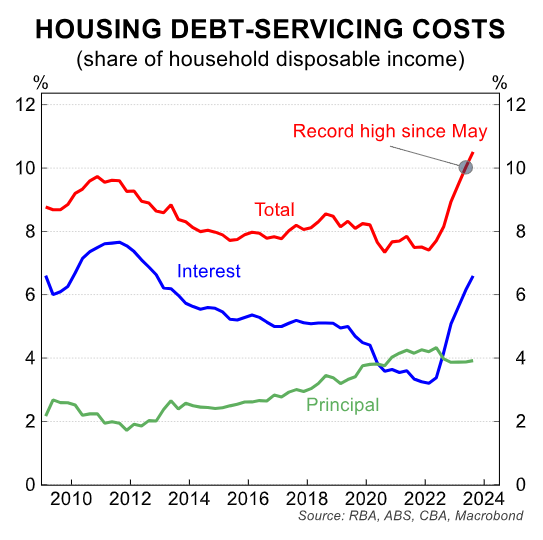

Households will also continue to be stung by record mortgage repayments, which won’t begin to moderate until after the RBA commences its easing cycle in the second half:

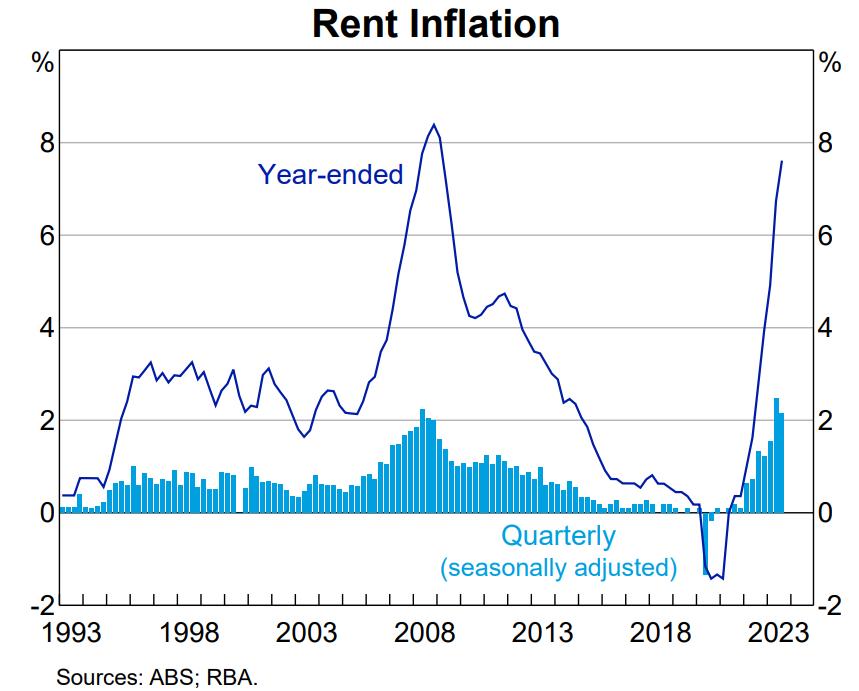

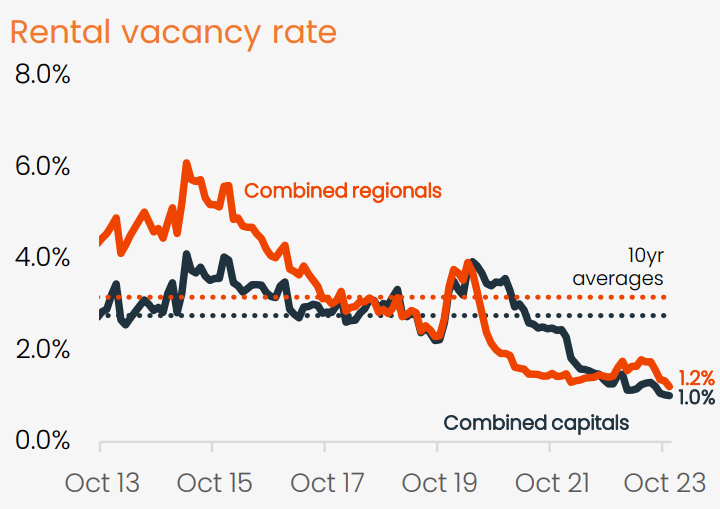

Rental inflation will also continue to rise above income growth over 2024, pressuring roughly one-third of households.

Historically high population growth (immigration) amid slowing housing construction means that rental vacancy rates will remain near record lows in 2024, ensuring ongoing strong rental inflation.

Source: CoreLogic

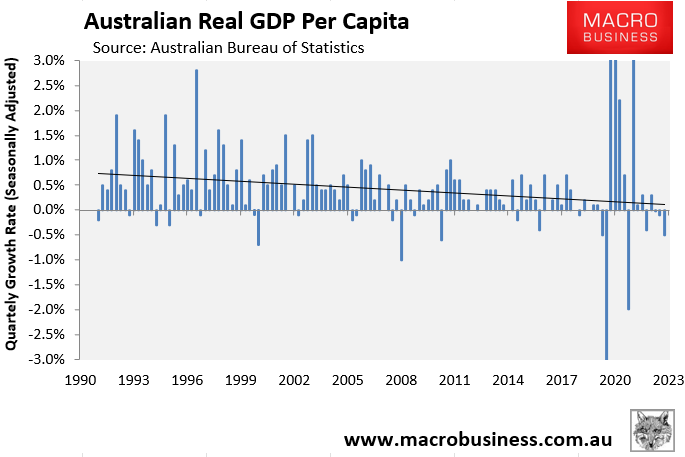

Australia’s per capita recession will roll on:

Australia’s real per capita GDP growth fell for three consecutive quarters to September 2023. This delivered a ‘per capita recession’ for Australians, meaning the overall economy grew modestly via record population growth, but everybody’s share of the economic pie shrank:

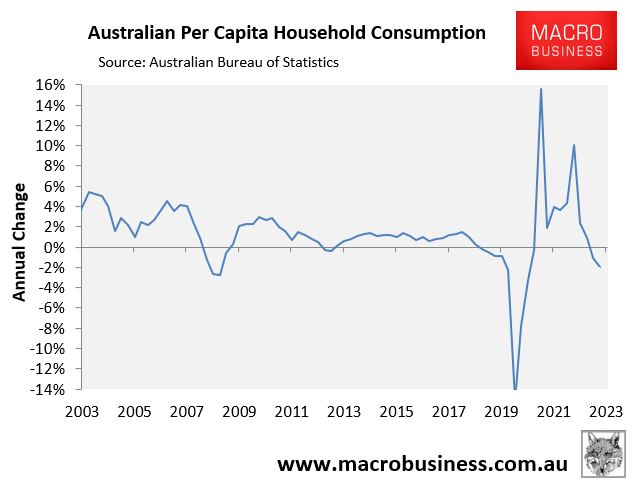

I expect the per capita recession to continue well into 2024 for the simple fact that per capita household consumption, which drives more than half of the economy’s growth, will likely contract.

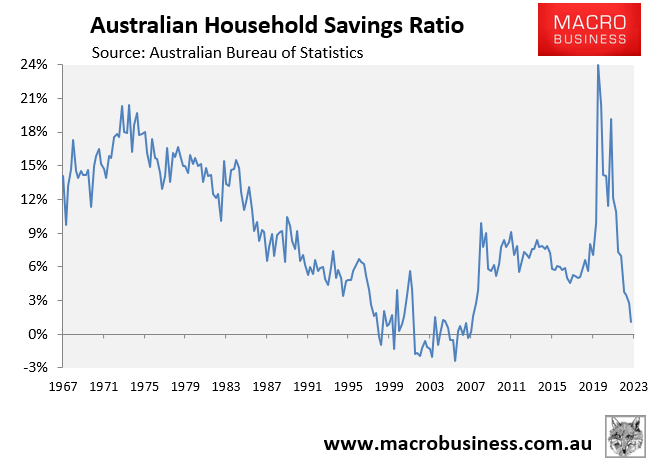

Household consumption fell by less (-1.9%) than incomes (-6.0%) in the year to September because households drew down on their savings:

As shown above, the household savings rate collapsed to a 15-year low in the September quarter.

With the savings rate already near zero, real per capita consumption will only increase via real income growth, which seems unlikely.

Indeed, with unemployment set to rise materially in 2024 (see below), real per capita household consumption could fall, extending the per capita recession for several quarters.

Unemployment to rise near 5% by end 2024:

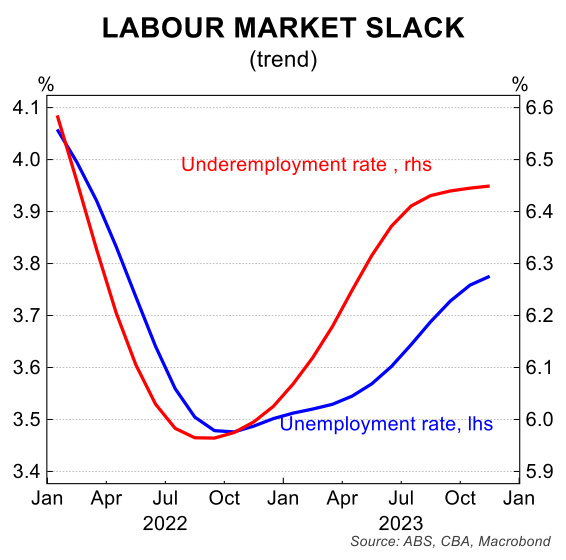

Australia’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate rose to 3.9% in November amid weakening labour demand and rising supply (trend data shown below):

With population growth forecast to remain historically high in 2024 (albeit lower than 2023), labour supply will continue to grow strongly.

Meanwhile, the demand for labour will continue to slow as the economy softens.

The upshot is that Australia’s unemployment rate will rise sharply, nearing 5% by the end of the year.

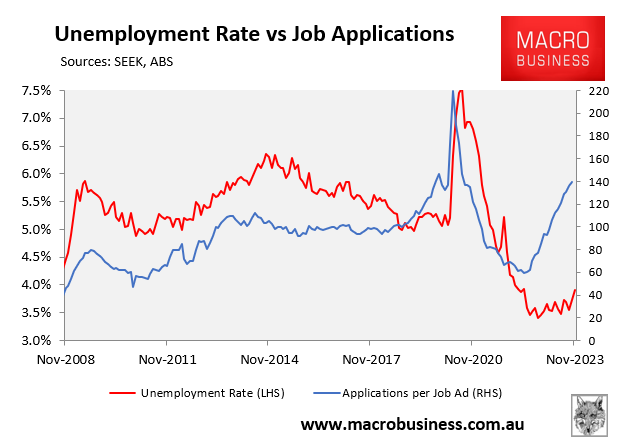

Indeed, the number of applicants per advertised job has already surged well above the pre-pandemic level and is pointing to sharply rising unemployment:

The Albanese government will continue to struggle in the polls:

The Albanese Labor government ended 2023 on a sour note, virtually head-to-head with the Dutton-led Coalition on two-party preferred (TPP) and lagging badly on primary vote.

With households remaining under deep financial pressure, the unemployment rate rising, and the rental crisis worsening, expect Labor to continue struggling in the polls through 2024.

Relief could arrive, however, late in the year as the RBA commences an interest rate easing cycle.

RBA won’t hike rates again and will cut in the second half:

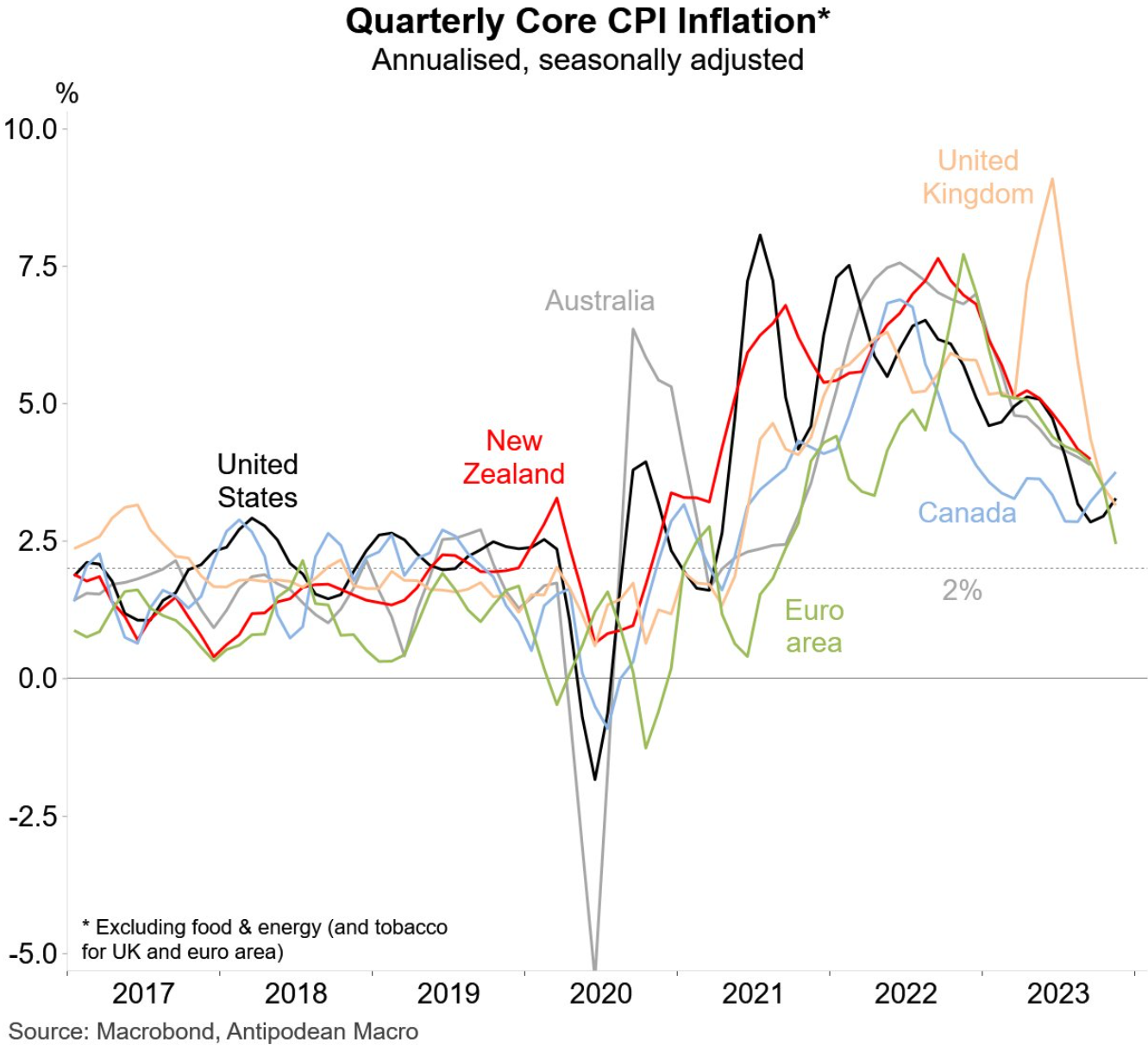

This is a big call, but the RBA is very likely done with rate hikes and will more likely cut in the second half as the economy weakens and inflation moderates.

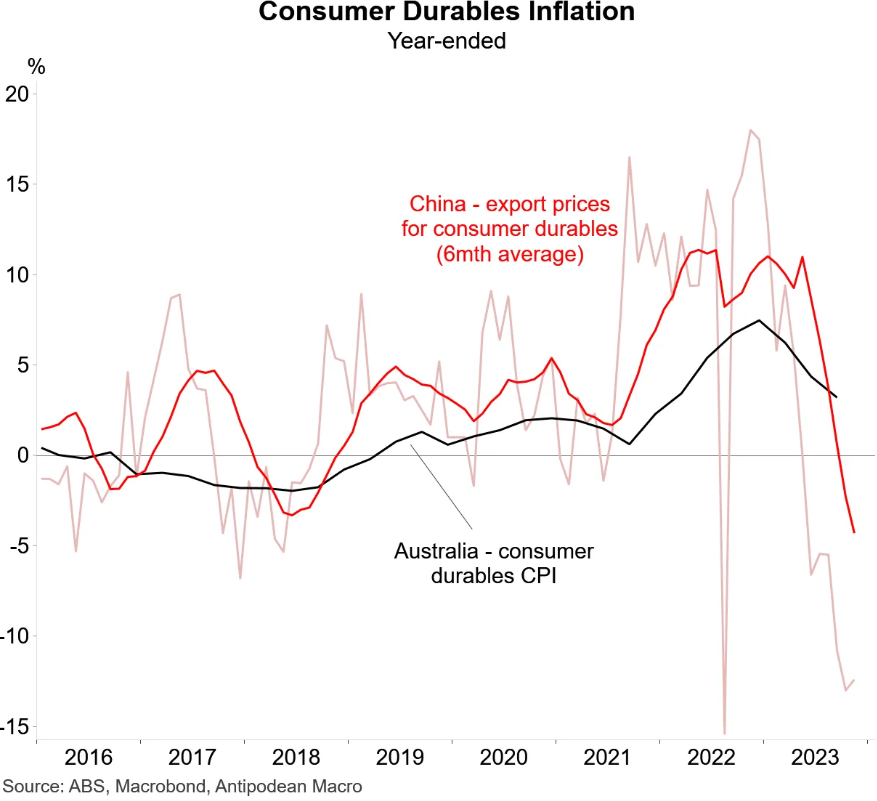

There is a global glut in goods at the moment. This means that anything that arrives in Australia via ship has been falling in price. It is basically the reverse of what happened during the pandemic when we had all these supply shortages.

Now we are seeing the supply side rebounding just as global demand has fallen.

So effectively, we have an over supply of goods and that’s now exporting goods deflation across the globe, including into Australia:

Most of the world’s central banks have likely finished their tightening cycles, which I believe will be replicated in Australia.

The RBA will then start cutting rates late in the year as inflation falls and unemployment rises.

The key ‘fly in the ointment’ here is whether the attacks on global shipping routes in the Middle East by Islamic militants worsen, disrupting global supply chains and causing goods inflation.

Regardless, it will be interesting revisiting these predictions in a year’s time to see how they panned out.