Stephen Anthony, chief economist at Macroeconomics, has called-for changes to prudential capital adequacy rules to incentivise Australia’s banks to refocus their lending towards productive SME businesses over unproductive housing:

“Before financial deregulation in 1983, Australia’s banking system allocated two-thirds of its capital towards local communities and small businesses. In other words, the focus was on value-added production and settlement”.

“Back then our banks were required to take their social licence seriously. Indeed, that is why we had state-owned banks and building societies. Private banks maintained expensive branch networks to compete for business”.

“Forty years after financial deregulation, Australia’s banking system allocates around three-quarters of its capital towards residential home loans (about half of which are made to investors). Sectoral profit margins are globally embarrassing”.

“All of this contributes to acute imbalances in terms of housing affordability and affordable housing via inflating the asset stock. Sadly, no one raises an eyebrow”.

“One obvious way to lower the cost of debt capital for SMEs would be to recalibrate prudential risk weights so that they become far more favourable to their lending”.

“That would also motivate our banks to roll up their sleeves and begin again to better understand the local business needs of their customers. And it might also take some of the heat out of residential property prices”.

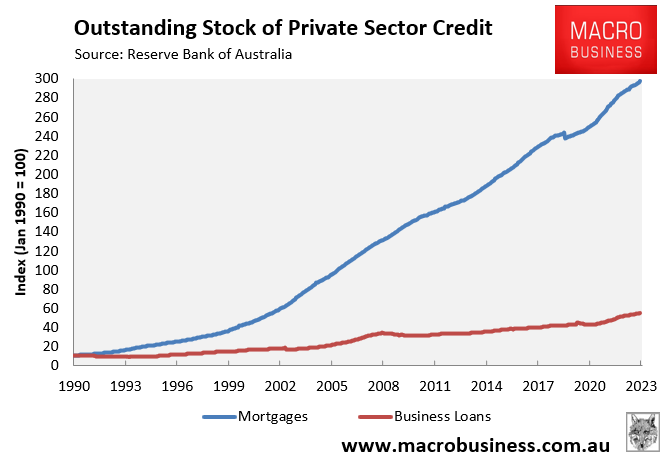

This problem has been decades in the making, as illustrated by the next chart showing mortgage lending exploding at the expense of business credit:

In 1990, nearly two-thirds of bank lending was to businesses. However, the script has since flipped, with banks now overwhelmingly lending to mortgage holders:

The problem is two-fold, namely:

- Lenders generally require some kind of collateral (e.g. property) before lending money to small businesses or start-ups; and

- The Basel Capital Adequacy framework, adopted by APRA, ascribes a much higher capital charge (8%) on standard business lending than for mortgage lending (2% to 2.8%).

The combination of high tax rates on savings, as well as generous tax breaks such as negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount, has also made investing in housing a relatively appealing option.

As a result, Australia’s tax policies have fostered a higher level of demand for housing than would otherwise exist, resulting in too much of the nation’s capital being tied-up in housing at the detriment of productive sectors of the economy.

The long-term solution, therefore, requires changing the capital adequacy and tax systems so that they reward productive investment.