The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) 0.25% increase in the official cash rate (OCR) last month had an immediate damping effect on housing values, particularly in Melbourne and Sydney.

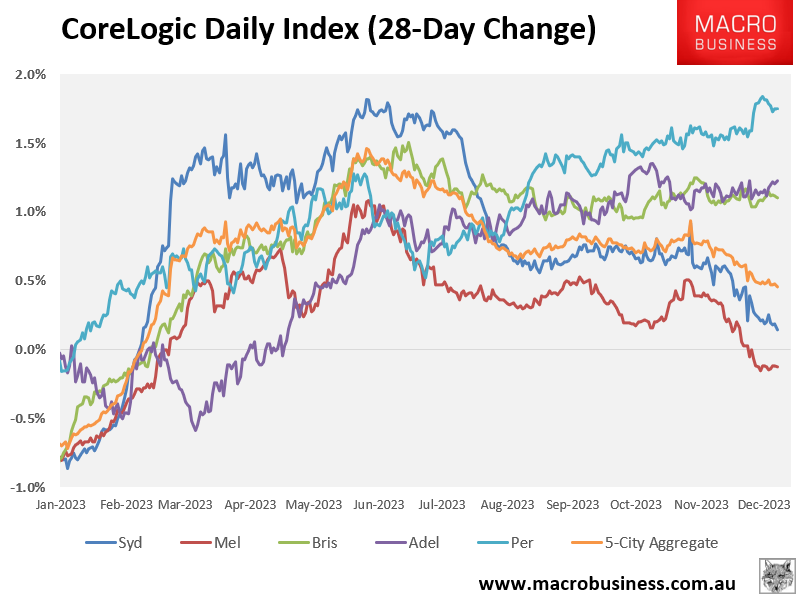

CoreLogic’s daily dwelling values index has recorded a sharp slowing in value growth at the 5-city aggregate level following the latest rate hike, driven by Melbourne and Sydney:

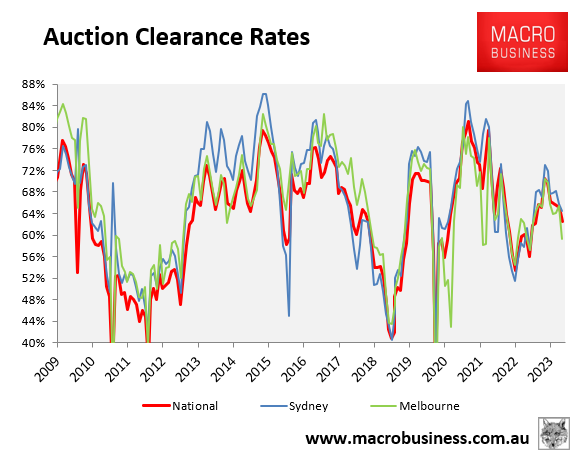

Auction clearing rates have also dropped significantly, indicating a significant loss in housing momentum.

At the combined capital city level, the monthly average clearance rate dropped from 71% in May to 63% in November.

The nationwide drop was driven by the two largest auction markets of Sydney and Melbourne.

Sydney’s auction clearance rate declined from 73% in May to 64% in November, while Melbourne’s clearance rate fell from 70% in May to 59% in November:

PropTrack last week predicted a 1% to 4% increase in national dwelling values in 2024, citing “a combination of continued strong demand and limited new housing construction”.

Other observers are less enthusiastic.

Tim Lawless, research director at CoreLogic, believes “that fragility in buyers’ demand has been exposed by the latest rate hike” and warned that Sydney and Melbourne could move “into a mild double-dip downturn in December and coming into early January”, with it “looking increasingly clear that the housing market is moving through a new inflection point”, and overall prices “generally weakening”.

In his latest Boom & Bust Report, SQM Research managing director Louis Christopher predicted property values to fall in five capital cities next year, as well as a significant likelihood of a negative national result.

“The interest rate rises of 2022, 2023 and possibly 2024 will finally start to bite homeowners and would-be homebuyers alike”, he said.

“Distressed selling activity is expected to jump, especially in NSW where we are already starting to see a new trend upwards in that data set”.

Shane Oliver, chief economist at AMP, stated that “Sydney and Melbourne house prices are decelerating faster than expected” and warned that “the supply shortfall-driven rebound in home prices this year is rapidly coming to an end as high rates get the upper hand again”.

Finally, in the face of record interest rate hikes, Stephen Koukoulas was one of the few economists who predicted the recent price rebound.

However, Koukoulas stated that the RBA’s rate hike last month “could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back” and forecast “between 3% and 5% drop in Sydney and Melbourne house prices”.

The RBA’s relentless monetary tightening and deteriorating affordability appear to have finally overtaken the record immigration volumes flowing into Australia, with Melbourne and Sydney leading the slowdown.

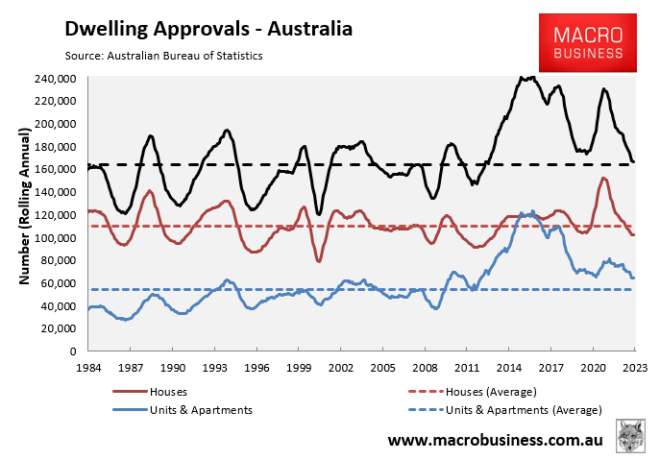

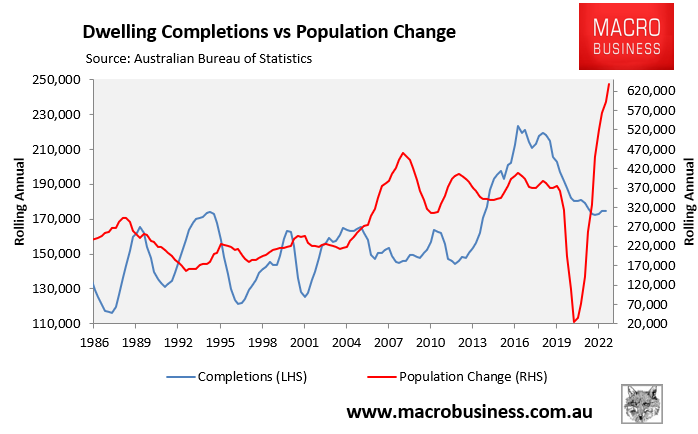

The greater concern is the decline in housing construction:

The RBA’s October monetary policy meeting minutes expressed concern that the “stronger than expected recovery” in Australian house prices “might provide some support to household consumption in the period ahead” and “could also be a signal that the current policy stance was not as restrictive as had been assumed.”

Therefore, the RBA would be encouraged by the significant slowing in Australia’s house price momentum following its most recent rate hike.

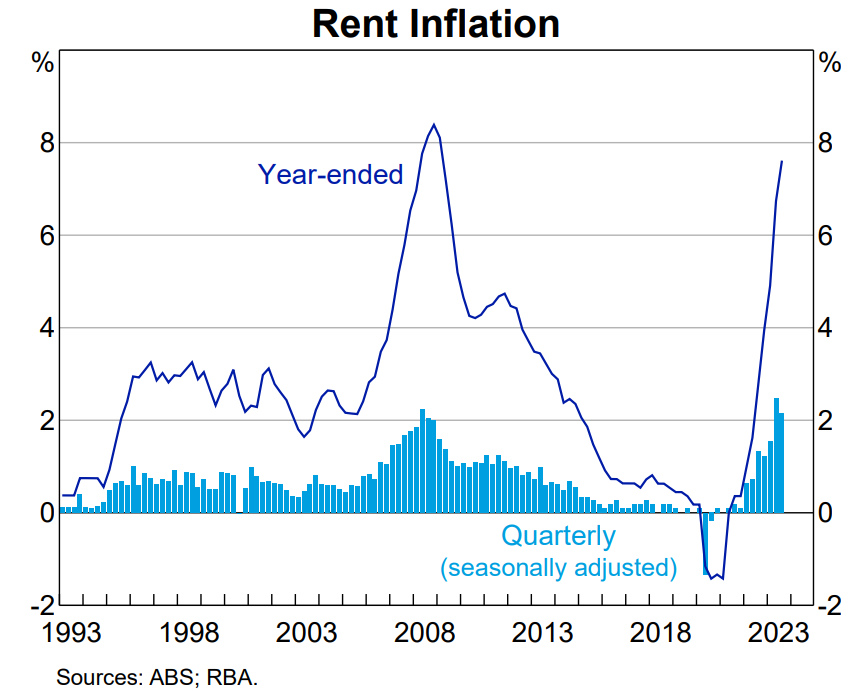

What the RBA would not be comforted by is the sharp downturn in the nation’s housing construction, which risks driving additional rental inflation in the face of record population growth.

Data released since the RBA’s Melbourne Cup day rate hike point to fewer homes being built and worsening housing shortages in the coming years.

According to the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) dwelling approvals data, only 164,200 homes were approved for construction in the year to October, the lowest reading in a decade and approximately 76,000 fewer than the Albanese government’s target of building 240,000 new homes per year:

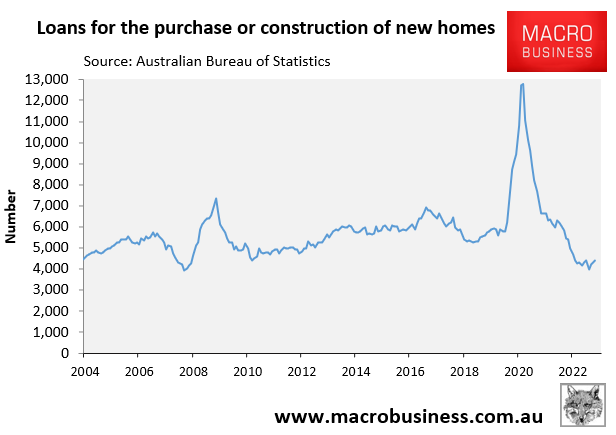

The ABS also reported that lending for the purchase and building of a new home remained at historic lows in October:

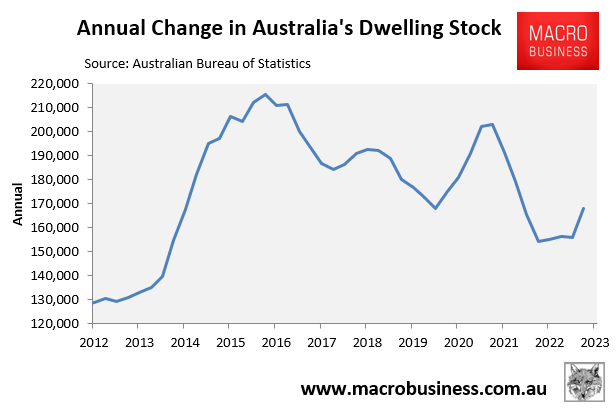

This month, the ABS also issued estimates of net dwelling additions, which account for demolitions.

The ABS estimates that Australia added only 168,000 dwellings to its housing stock in the year to September 2023:

Indeed, since the series began in September 2011, the strongest year for the increase in dwelling stock was the year ending September 2016, when the number of homes increased by 215,500.

Even this record year of housing production in 2016 fell far short of the Albanese government’s five-year aim of 1.2 million homes, which requires 240,000 homes to be built each year.

According to Tim Reardon, Chief Economist of the HIA, the RBA’s aggressive interest rate hikes have cratered demand for new homes as well as new home development.

“In the face of an acute shortage of housing stock, the rise in the cash rate has seen the volume of work entering the pipeline contracting for more than two years”, Reardon said via media release following the latest batch of statistics.

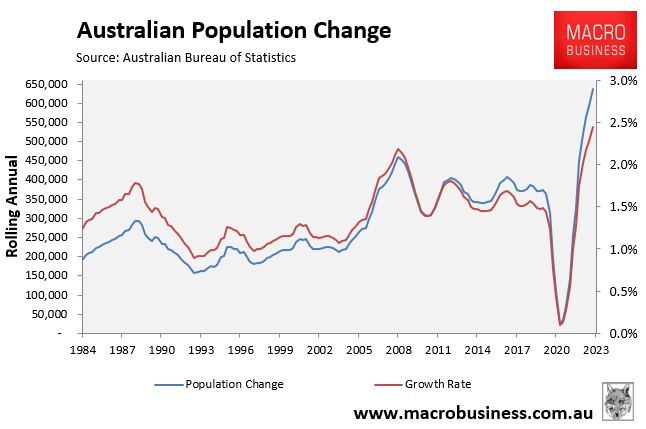

The housing supply crisis has been exacerbated by Australia’s record-breaking population increase, which has resulted from the largest net overseas migration in the country’s history.

According to the ABS’s September quarter national accounts, which were released on Wednesday, Australia’s population expanded by a record 638,000 in the year to September, owing to an estimated net overseas migration of roughly 500,000 persons:

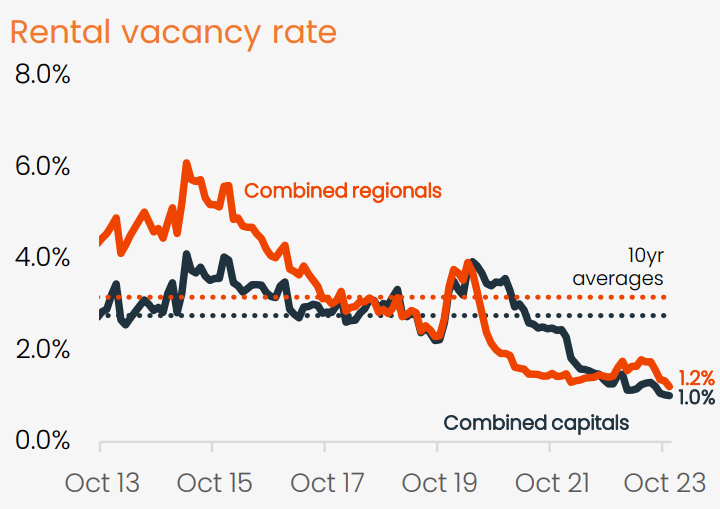

So, while Australia’s population is surging, actual dwelling completion rates are falling, which explains why the country is suffering record-low rental vacancy rates, soaring rental inflation, a rise in Australians living in group accommodation, and rising rates of homelessness.

Source: CoreLogic

The housing situation in Australia will only worsen next year as continued high population demand meets diminishing supply:

This will also create problems for the RBA because rents are the second largest single component of the Consumer Price Index, and rapid rental growth is directly contributing to Australia’s inflationary pressures.

With Australia’s housing construction capacity hampered by high lending rates, rising material costs, worker shortages, and widespread insolvency, the Albanese government’s only plausible solution to the country’s housing crisis is to heavily cut immigration.

Otherwise, Australia’s rental crisis will worsen, and inflationary pressures will persist as demand continues to surpass supply due to strong population growth.

Australia will never be able to build enough homes so long as its population continues to expand rapidly via high levels of immigration.