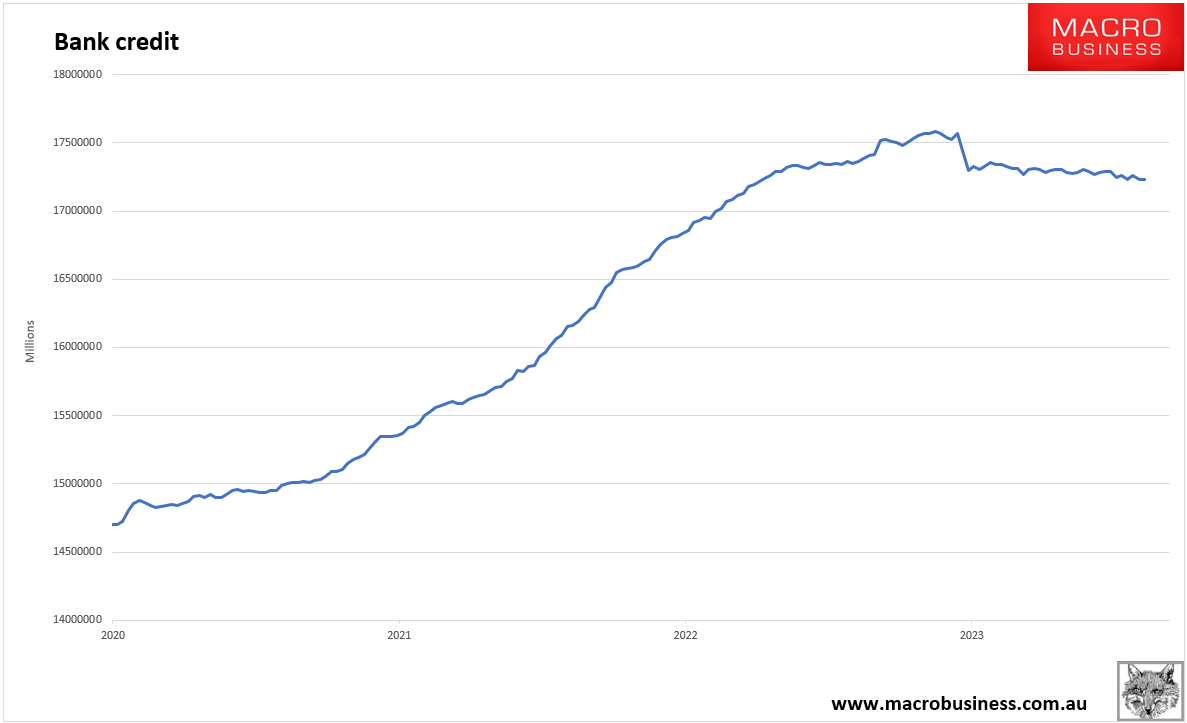

This has to become a problem soon. Lending has not grown in nearly eighteen months:

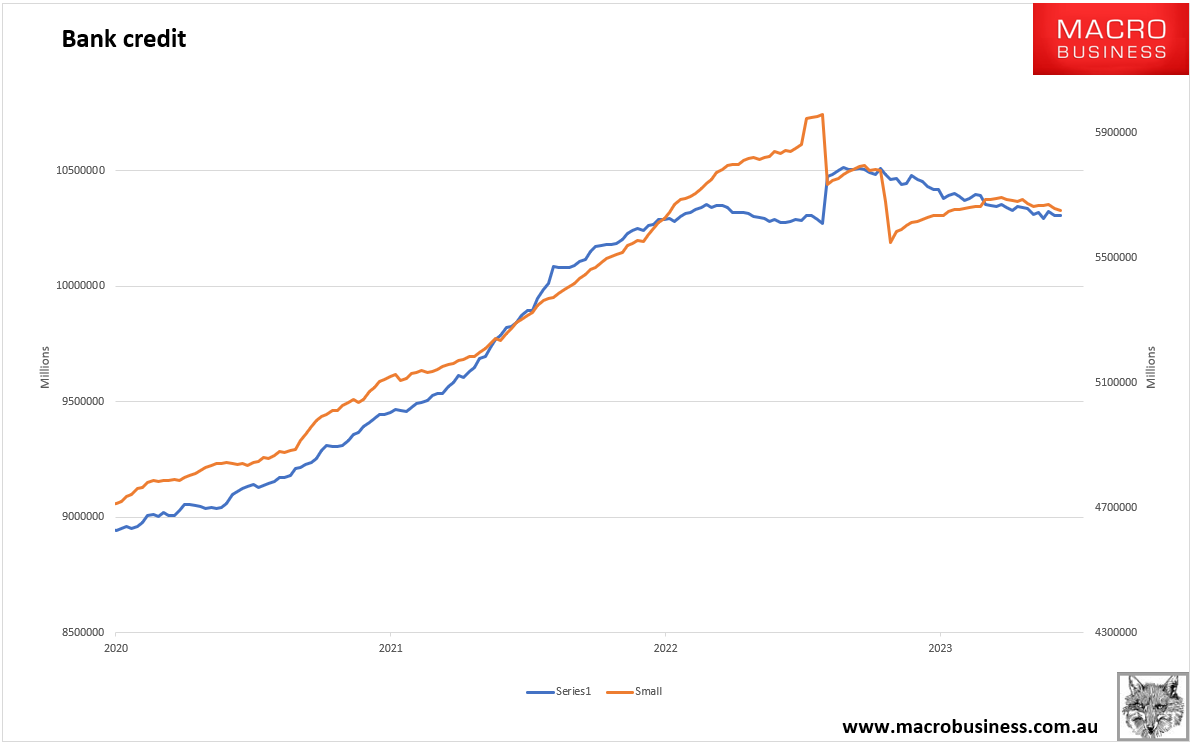

Neither large nor small banks:

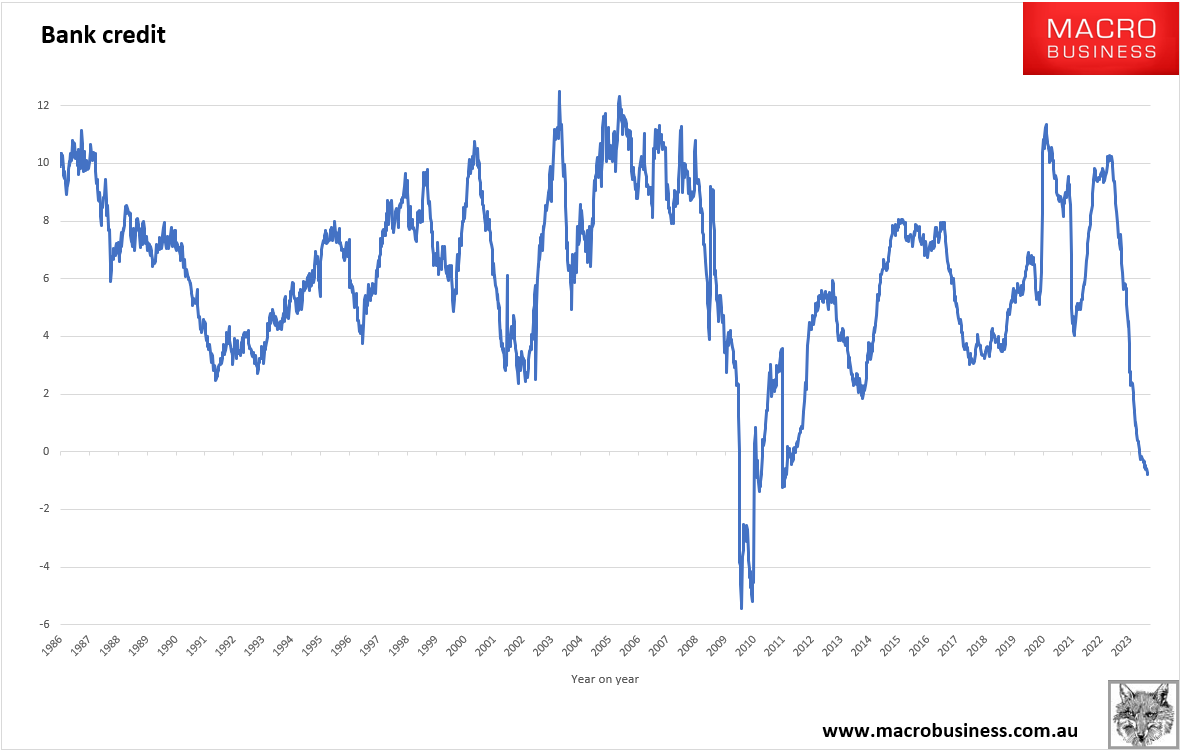

The year-on-year says it all:

In no cycle has bank debt fallen so far without triggering a recession.

There is still market-based debt for larger corporations that can add to private-sector debt growth.

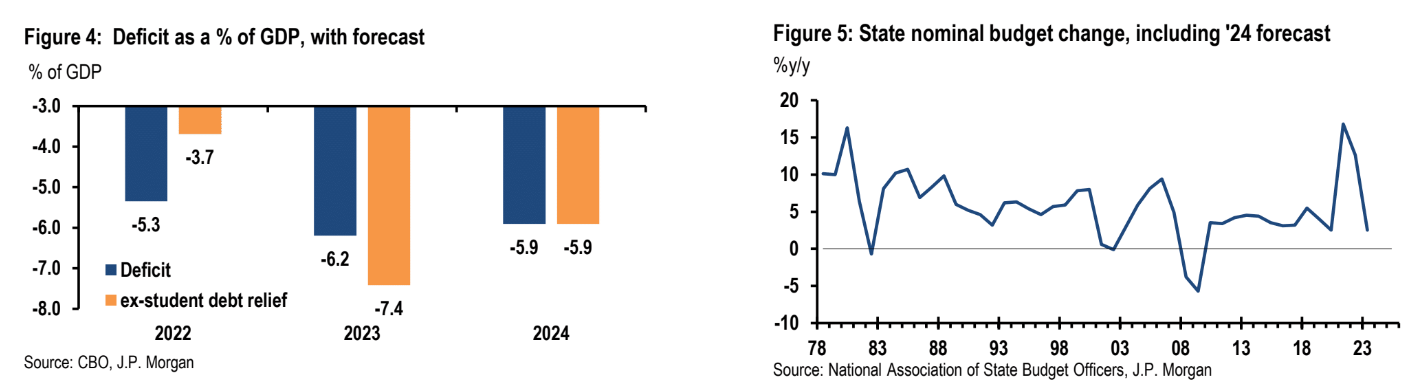

But public debt is another tailwind turning headwind. JPM has more.

An important offset to monetary tightening has been fiscal easing. This fiscal accommodation was somewhat masked by the unique way the White House’sstudent debt relief plan was accounted for, even though that plan never went into effect. Removing that accounting quirk, the federal deficit on a cash flow basis expanded from $950 billion, or 3.7% of GDP, in FY22 to $1.839 trillion, or 7.4% of GDP, in FY23(Figure 4).

One common way of measuring how much push or pull the federal government is exerting on aggregate demand is to look at the change in the deficit (usually as a percent ofGDP).

The 3.7%-point increase in the cash flow deficit this fiscal year would be the third largest since 1950, after FY08 and FY20.

However, much of this year’s expansion in the deficit wouldn’t qualify as your classic stimulus. Some of the large swing factors include reduced capital gains taxes, higher interest payments, and a big COLA adjustment for social security.

All of these respond automatically to changing economic conditions.

Even so, it would be odd to call these“automatic stabilizers” as the economy has been performing well—just the opposite of when automatic stabilizers should boost the deficit.

But however you want to classify it, relative to FY22, in FY23 the federal government is taking in a lot less cash than it is sending out, and those funds have to end up in somebody’s hands.

So it’s hard to believe that almost $1 trillion more spending not matched by taxes is not offsetting some of the restraint imposed by the Fed.

The story looks different when we look ahead to ’24. The Fiscal Responsibility Act is set to reduce spending in this fiscal year by $70 billion.

The suspension of the Employee Retention Credit and affiliated credits should reduce spending by another $52 billion.

All told, even after accounting for increased interest outlays, we expect the federal deficit to narrow to 5.9% of GDP (Figure 4).

While this is still a huge full-employment deficit, recall that fiscal impetus looks at the change in the deficit, and after a huge positive fiscal impetus last year, developments at the federal level should deliver modestly negative fiscal impetus in the coming year.

We have less clarity at the state and local levels of government, but believe developments there are moving in the same direction.

The ARP pumped hundreds of billions into state and local coffers. Spending followed. State and local balance sheets remain in great shape.

However, in the aggregate governors are now proposing more modest nominal spending growth of 2.5% in 2024 (Figure 5).

Soft or hard, the US economy is coming into land, and it will be bumpy.