Back in April, Ernest & Young released a report, commissioned by the Property Council of Australia (PCA), claiming that providing federal budget support for build-to-rent (BTR) housing could increase housing supply by 150,000 homes over 10 years.

“The potential to create 150,000 homes over the next 10 years with just one asset class shows build-to-rent is about as close to a housing policy silver bullet as they come”, PCA chief executive Mike Zorbas said.

The latest federal budget bent the knee to the PCA by increasing tax incentives for BTR projects, namely:

- increasing the depreciation rate for eligible BTR projects from 2.5% to 4%, and

- reducing the ‘managed investment trust’ withholding tax rate for eligible BTR projects from 30% to 15%.

A BTR project is eligible for these tax breaks provided it includes at least 50 units, the units are under single ownership for at least ten years, and renters are offered a lease term of at least three years.

In announcing the measures, the federal budget explicitly referenced the PCA’s claim that “this could unlock 150,000 rental properties over 10 years, boosting the supply of high-quality, long-term rentals in the Australian market”.

I have long held the view that BTR is an affordability gimmick that adds a layer of profit-dependent corporations to the housing “market”, thereby increasing the sector’s already strong lobbying and pricing power.

Furthermore, since most BTR projects are provided by foreign-owned corporations, tax breaks and rental profits will flow offshore rather than to domestic ‘mum and dad’ investors.

A classic example of the BTR affordability mirage was on display over the weekend at The Guardian, which reported the following:

When tenants moved into 43 brand new apartments at a building in Melbourne’s inner north 12 months ago, some thought they would be there for years.

The apartments at 221 Kerr Street, Fitzroy, were marketed as setting “a new standard for apartments in the suburb”. There was a competitive application process, with some prospective tenants asked to send in biographies explaining why they should live there.

A year later, some residents claim about one-third of the building has received either notices to vacate or rent increases. Of the 43 apartments, a group of residents claim the tenants of seven apartments have received notices to vacate and eight have received rent increases of between 9% and 17%.

“We’re being evicted in the middle of a housing crisis,” says Ella, who did not want her real name published and who has to move out along with her housemate…

Housing advocates argue the situation raises concerns about corporate landlords…

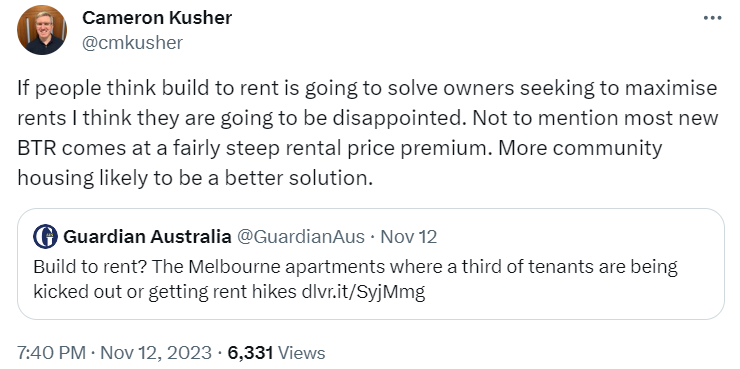

PropTrack head of research, Cameron Kusher, suggested on Twitter (X) that most BTR “comes at a fairly steep rental price premium”:

Dr Cameron Murray, a Sydney University economist and housing supply expert, has also been sceptical about whether BTR provides tangible benefits to local tenants:

“Existing build-to-rent projects are predominantly high-end luxury apartments, and the owners of them report to investors how successful they are at charging more than the local market rent by bundling in premium features like fancy gyms, food services. Is this something that we should be providing subsidies to?”.

“There is already a huge wave of build-to-rent projects under current tax rules, so it is not clear why more tax breaks are needed”.

Ross Stitt, a freelance writer with a PhD in political science, raised similar concerns about BTR recently:

“The concept is a high standard of apartment in a complex with generous amenities, often in sought-after inner-city suburbs”.

“The quid pro quo of ‘high-quality’ is of course a premium rental rate for the landlord. That’s the element that makes BTR attractive to institutional investors”.

“Presumably, investors of this calibre know what they’re doing. The only question is whether enough Australians will be able to afford the higher rents demanded by BTR”.

A recent Charter Keck Cramer survey of comparable one and two-bedroom apartments showed that BTR projects charged a 20% premium on traditional rentals.

“Advertised rents at Mirvac’s LIV Indigo BTR development in Sydney Olympic Park and rents for nearby private rental apartments shows the median one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment rent is 19% higher than an equivalent build-to-sell unit, while the difference was 27% for a two-bed unit”, The AFR reported.

So, rather than fixing the rental crisis at the source by lowering net overseas migration to a level below Australia’s capacity to build homes and infrastructure, BTR is another ‘affordability’ mirage spruiked by rent-seekers for their own benefit.

Let’s be honest: BTR is another vehicle aimed at institutionalising wealth into fewer hands.