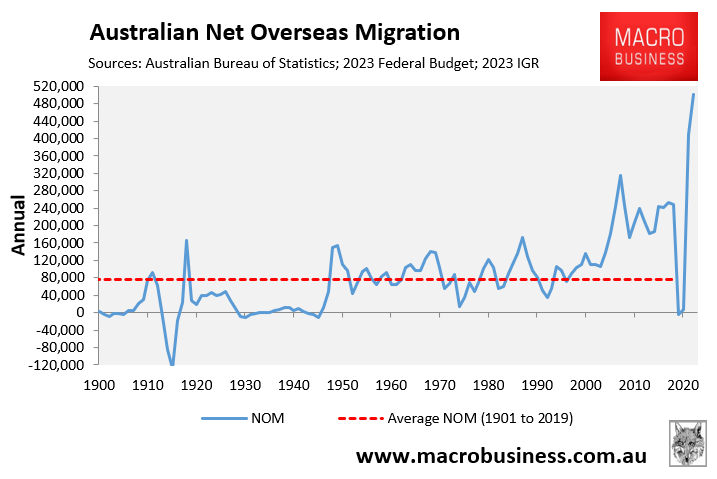

Last week, economist Gerard Minack published a brilliant analysis detailing how Australia’s productivity growth and living standards have been harmed by nearly two decades of historically high immigration.

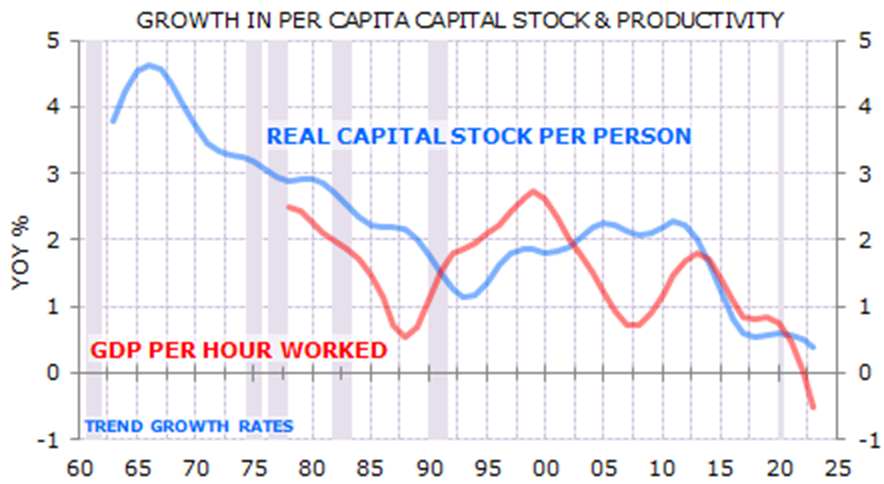

Minack’s key chart presented below illustrates that Australia has experienced significant capital shallowing due to the inability of infrastructure, housing, and business investment to keep pace with the nation’s bulging population:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, wrote Minack.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, warned Minack.

Minack’s assessment mirrored many of the arguments that I have put forward regarding Australia’s mass immigration policy for the past decade (most recently this month).

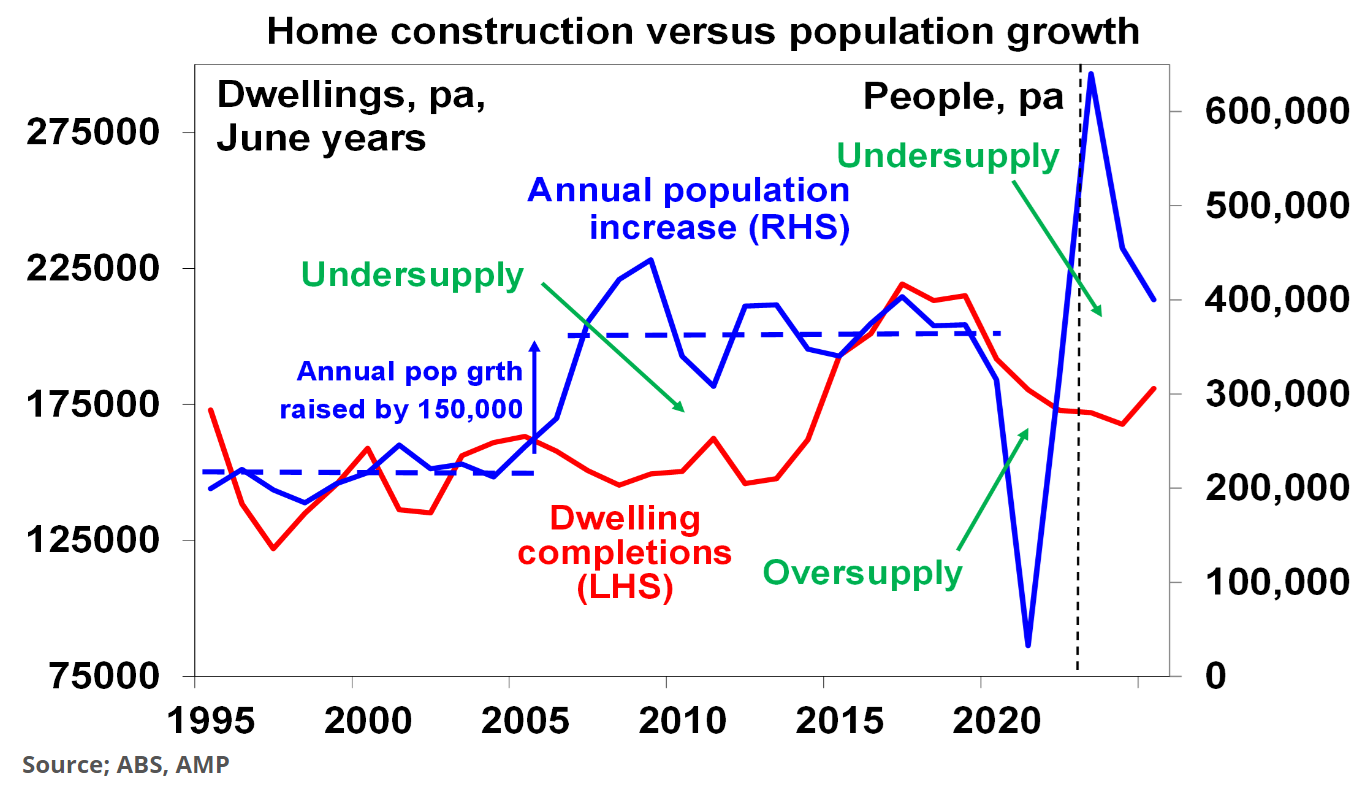

AMP chief economist, Shane Oliver, also made similar arguments in August when he noted that “very strong population growth with an inadequate infrastructure and housing supply response has led to urban congestion and poor housing affordability which contribute to poor productivity growth”.

Last week, AFR economics editor, John Kehoe, cautioned that “business start-ups are declining among younger generations and rocketing property prices may be to blame”, which is hampering Australia’s productivity performance.

“The high cost of residential property may be impeding entrepreneurship in at least two ways”, explained Kehoe.

“First, because land has become so expensive (to both buy and rent), this makes it harder for people to take time off a regular job and take the risk of starting a new business venture”.

“Second, RBA research suggests that high house prices relative to incomes make it harder for young entrepreneurs to access business finance”.

Kehoe warned that less entrepreneurialism is bad for the economy and productivity because “new business start-ups are disruptors, innovators and competitors”, they “knock out old cossetted incumbent businesses and introduce new products to the market”, and put “downward pressure on prices”.

Obviously, one of the key drivers of the nation’s expensive housing is strong immigration, which has overwhelmed supply.

As noted by AMP chief economist, Shane Oliver, “the role of immigration in the demand/supply mismatch is critical” to Australia’s housing shortage.

“Starting in the mid-2000s annual population growth jumped by around 150,000 people on the back of a surge in net immigration levels – see the blue line in the next chart”.

“This should have been matched by an increase in dwelling completions of around 60,000 per annum but there was no such rise in completions until after 2015 leading to a chronic undersupply of homes – see the red line”.

“The unit building boom of the second half of last decade and the slump in population growth through the pandemic helped relieve the imbalance but the unit building boom was brief and a decline in household size from 2021 resulted in demand for an extra 120,000 dwellings on the RBA’s estimates”.

“The rebound in population growth has taken the property market back into undersupply again”.

Westpac chief economist, Luci Ellis, also argued on Friday that the recent sharp decline in Australia’s productivity performance could be explained by the sharp growth in low-paid jobs:

“People have not individually become less productive; there are simply relatively more low-paying jobs than before, which account for less GDP per hour”, Ellis said.

“If true, this is a level shift effect and should not have a lasting effect on growth in productivity”.

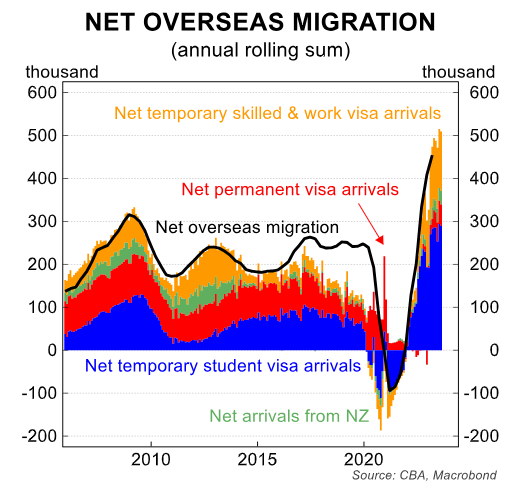

The sharp rise in low-paid jobs is obviously being driven by the flood of international students into Australia, most of whom work in said jobs:

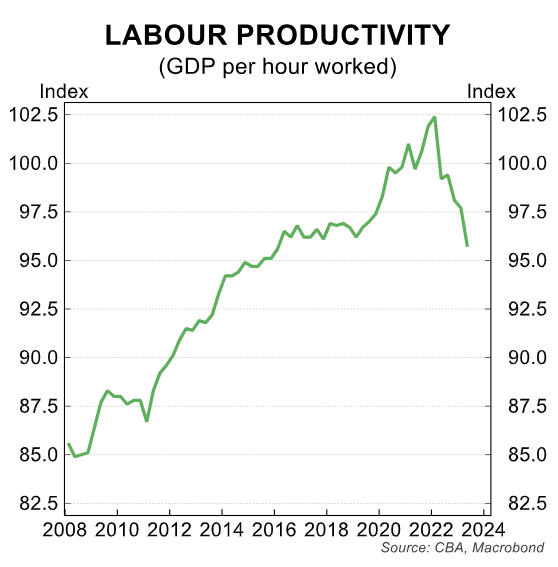

Australia’s labour productivity growth surged when Australia’s net overseas migration turned negative over the pandemic:

Australia enjoyed a period of “capital deepening” as the nation’s capital stock was spread over fewer people, which boosted productivity.

However, now that net overseas migration is running at record levels, productivity growth has collapsed due to “capital shallowing” as the nation’s capital stock was spread over more people.

The migrants that come to Australia earn less than the median salary.

The increased labour supply induced by high immigration also puts downward pressure on wages, causing businesses to avoid investing in labour-saving technologies and automation, which also reduces productivity.

After all, why invest in productivity savings when you can instead hire low-cost migrant workers?

Large-scale immigration also diverts resources, encouraging expansion in low-productivity “people-servicing” industries while focusing the nation’s productive effort into infrastructure and housing.

Policy makers and economists need to dispel the myth that large-scale immigration boosts productivity and living standards.

Because the empirical evidence from 20 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration shows the polar opposite.