An Australian study by the Mackenzie Research Institute at the Holmesglen Institute in Melbourne revealed that while university degrees help holders gain employment, they do not ensure success.

Although those with a university education hold the highest-paying and most prestigious positions, their proportion of low-paying jobs is also increasing.

This often results in the displacement of individuals who possess only diplomas and trade certificates, thereby displacing workers who have gained minimal or no postsecondary qualifications.

Dr. Tom Karmel, former executive director of the National Centre for Vocational Education Research, remarked that the results raised questions about the “never-ending push” to increase the number of Australians with degrees.

“There’s no doubt that the occupations where people need degrees are growing faster than others, but the rate of credential growth has been so much greater than that”, he said.

“Credentials are becoming increasingly important even in lower paid jobs”.

“Is it skills deepening or is it really just blatant credentialism? It’s probably a bit of both. If everybody had a degree, a degree would be useless”, he said.

Dr. Karmel’s analysis used information from the 2011 and 2021 Australian censuses.

During that decade, the proportion of individuals holding postgraduate degrees in the labour force increased from 5% to 9%, and the number of individuals holding such degrees more than doubled, from approximately 500,000 to nearly 1.1 million.

Currently, around 3.1 million individuals hold undergraduate degrees, which accounts for 26% of the total Australian labour force.

Master’s or doctoral degrees were held by approximately 2% of labourers, machine operators, and technicians, 3% of salespeople, and 6% of clerical and administrative personnel in 2021.

Around four times as many individuals held bachelor’s degrees in each of these fields.

The over-credentialism situation would only worsen under the Albanese government’s Universities Accord interim report, commissioned by Education Minister Jason Clare.

The higher education attainment target outlined in this report is 55% by 2050. To achieve this, an additional 300,000 domestic undergraduate students are projected to be enrolled by 2035, and 900,000 by 2050.

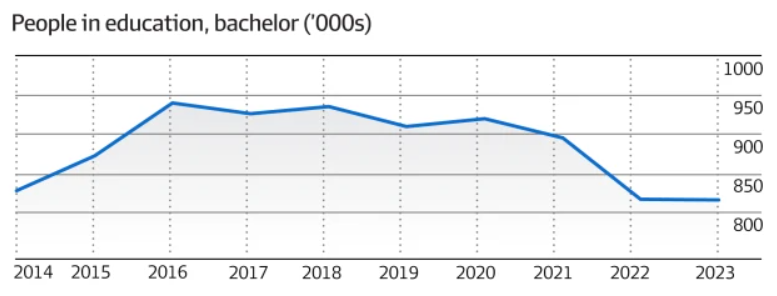

However, Australians are voting with their feet against these targets, with the number of Australian students studying for a bachelor’s degree falling more than 13% since 2016, according to new data presented in The AFR:

“It makes me think that maybe we have reached peak higher eduction,” said Peter Hurley, director of the Mitchell Institute at Victoria University.

Higher education expert Andrew Norton said for the federal government’s 2050 goal to be reached, everyone with an ATAR of 45 or higher would have to go to university. “On current levels of academic performance, large numbers of people don’t want to go to university,” he said.

While foreign students shore up numbers at most universities, the number of Australian students studying for a bachelor’s degree has fallen from 939,000 in 2016 to just 815,700 this year, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics data…

At the same time, enrolments in work-based training, such as apprenticeships, has risen sharply over the past couple of years…

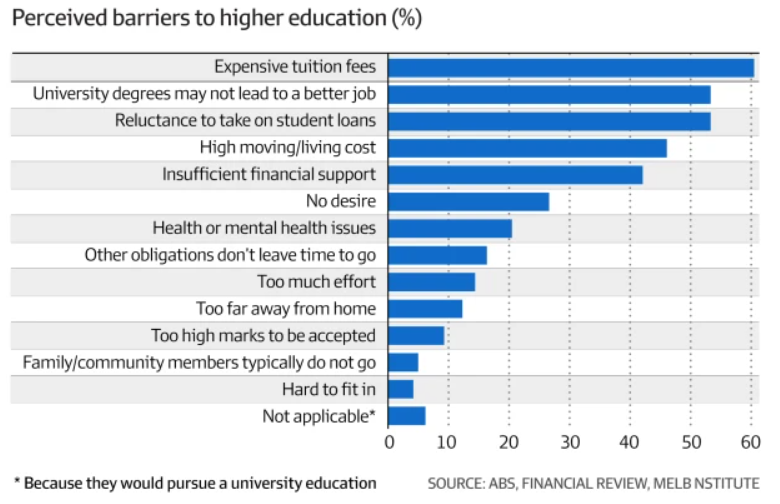

Data from its Taking the Pulse of the Nation survey found nearly 60% of people believed expensive tuition fees was the main barrier to people taking on university study.

Shockingly, 52% of people said university might not lead to better job outcomes, while the same proportion said too much student debt was a barrier. These perceptions were equally shared between people who already had a degree and those who had never attended.

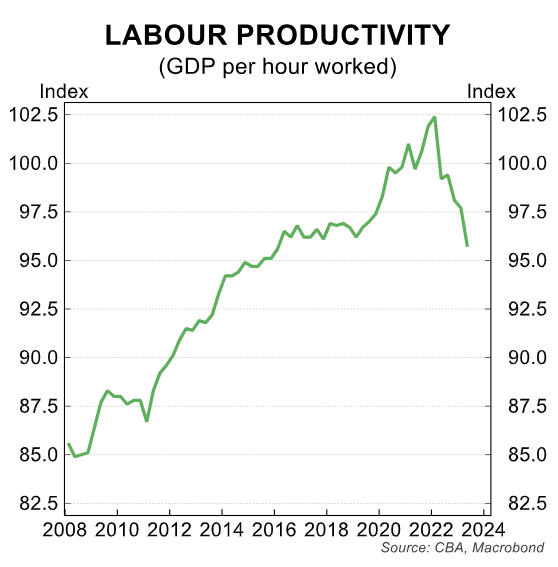

One of Australia’s biggest economic paradoxes is that while we have large numbers of university graduates in the labour force, the nation suffers from poor productivity growth and there are never-ending “skills shortages”:

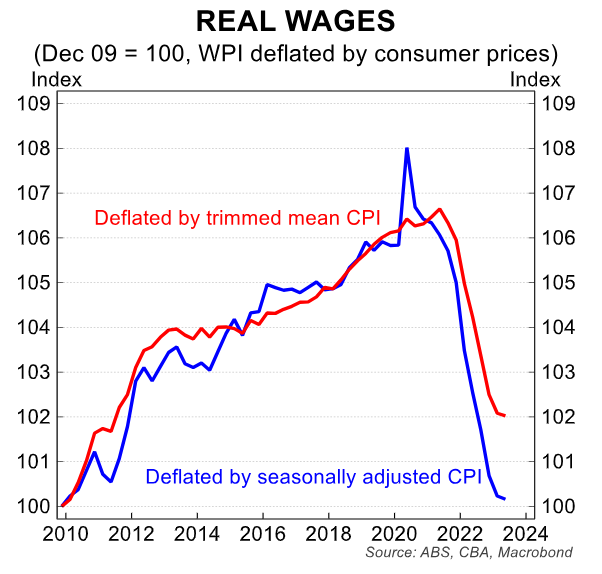

Real wage growth in Australia has also fallen amid the boom in university graduates:

Why does the Albanese government even want to have 55% of Australians aged 25 to 44 hold a bachelor’s degree or higher?

The majority of employment positions in Australia mandate a university degree, not due to any particular skill requirement or demand, but rather as a lazy “signaling” device used by employers to sort job candidates.

This “credential inflation” has expanded university enrolments while contributing next to nothing of benefit to the economy or society as a whole.

A university degrees’ worth has diminished as the number of individuals pursuing higher education has increased to the point where too many people now hold a degree.

The current situation is so absurd that, currently, a university degree is even a prerequisite for entry-level positions, which were previously filled just fine by individuals holding only a high school diploma.

In the process, public funding has been reallocated from TAFE and vocational training, which have experienced a decline in popularity. This has created chronic skill shortages in numerous fields (most notably the trades).

Universities have evolved into self-serving parasites driven by profit, graduating too many students who would have been better off pursuing a vocational course.

Australia’s priorities around higher education need change.

First and foremost, admissions policies to universities should be more stringent for both domestic and international candidates. Governments should also increase funding for VET and TAFE.

Prioritising universities above vocational training or trade schools was never in Australia’s social or economic interest.

Labor’s 55% university attainment target needs to die. If anything, Australia needs fewer people studying at universities and more attending TAFE, VET or undertaking apprenticeships.