Independent economist Tony Alexander wrote a research note explaining how record net overseas migration into New Zealand has caused a rapid easing in the labour market, which should lead to lower wage inflation.

In turn, the falling wage inflation should make it easier for the Reserve Bank to lower interest rates; although it could take some months to work through the situation.

Similar forces will be at play in Australia regarding wages. However, the record levels of immigration are also pushing up housing inflation (particularly rents and construction costs), which is more than offsetting any reduction in wage inflation (while making life harder for Australian workers).

Lower inflation lies ahead – still

On Tuesday NZIER released the latest results from their long running Quarterly Survey of Business Opinion and they show some clear developments of relevance to monetary policy particularly.

When a price shock hits the economy, with soaring oil prices being a frequent candidate, the annual rate of inflation will lift and probably exceed the top of the 1% – 3% target range.

However, the Reserve Bank are not required to raise interest rates to prevent this happening. Such shocks are considered transitory and get “looked through”.

Instead, what they are interested in are the second-round effects of this offshore driven reduction in our income purchasing power.

If employees seek to offset the rise in prices for consumer goods by boosting wage claims, then businesses are still left with a rise in costs exceeding the extent to which they have already increased prices. So, chances are they will raise their prices again and we end up with a wage-price spiral.

What matters a lot, then, following the pandemic/supply chain/oil price shock is the extent to which wages keep rising at a fast pace in New Zealand.

This matters perhaps more than in other countries because our labour market is very deregulated and that means changes in the balance of supply and demand can have a quick wages impact and if labour is in short supply cost of living shocks are highly likely to lead to much higher wage claims. Such has been the case for the past couple of years.

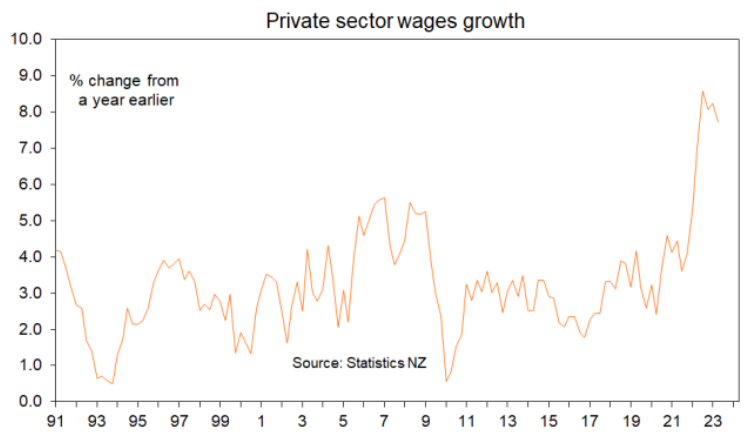

The annual rate of wage inflation rose from 2.6% in 2019 to 4.6% in 2020, 4.1% in 2021, 8.1% in 2022, and now sits at 7.7% in the year to June 2023.

With our business sector containing a high number of duopolies and oligopolies these wage rises are going to get passed on without the businesses concerned feeling much pressure to boost capital spending in order to raise productivity.

So, if the labour market eases up and reduces the ability of employees to seek compensation for cost of living increases this has a big impact down the line on inflation. That is probably what is happening now though it will take some time for this effect to truly show through.

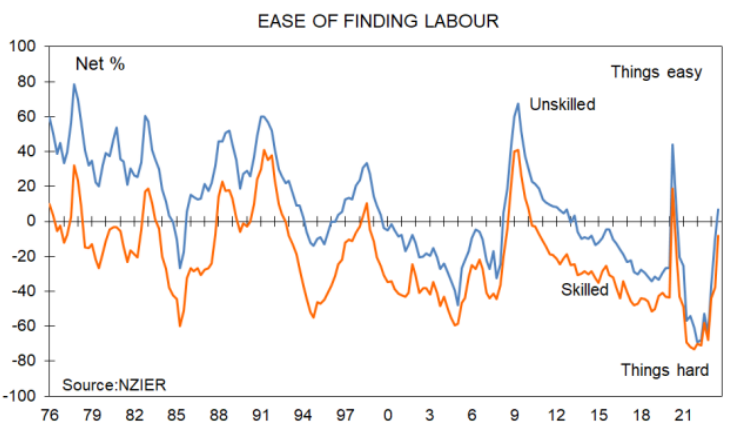

At the end of last year a net 68% of non-farm businesses in the NZIER’s QSBO said that they were having difficulties sourcing skilled labour. The ten year average reading for this measure is 39% and the pre-pandemic reading was 43%.

Now, courtesy of the migration boom, only a net 8% of businesses say that it is hard to get skilled people. This is an extremely rapid and large change which takes this measure to its least tight level since late-2010 if we ignore the immediate pandemic panic in 2020.

The same shift in ease of finding labour is seen for unskilled staff. A net 7% of non-farm businesses are reporting that it is easy to get unskilled staff. This measure was a net 64% saying getting unskilled staff was hard at the end of 2022 and the ten year average is 21%.

The reading is the loosest since 2015 – again ignoring the immediate pandemic effect.

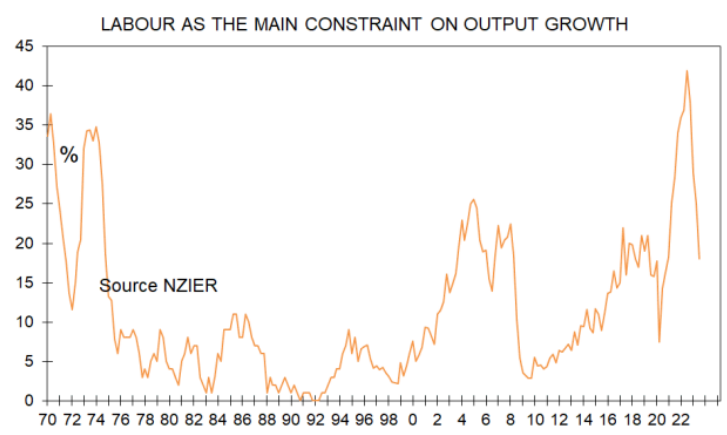

Not only that, but the proportion of businesses saying that the main reason they cannot expand production is lack of staff has fallen to 18% from 38% at the end of last year.

These data tell us that while the boom in migrants is visually concentrated at the low-skilled end of the labour market, there is a substantial impact further up the chain as well. The results strongly imply that wages growth is set to slow down quite a bit and that is something highly relevant to monetary policy.

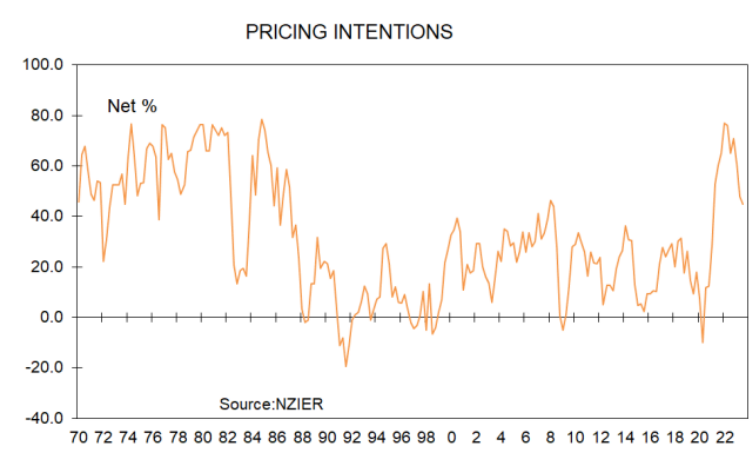

But while it looks like second round effects of the cost of living shock are set to be constrained, actual pricing plans by businesses haven’t yet undergone enough of a shift for us to say that the case for inflation getting back close to 2% is set firmly in concrete.

In the NZIER survey a net 45% of businesses have said they plan raising their selling prices over the coming three months. This is down from 71% at the end of last year so the direction of change is good. But the ten year average reading for this measure is 29%.

So, the time is not at hand when we can say the slowing economy and rapidly easing labour market are combining to slash plans by businesses to raise the prices they charge you and I. Inflation is not yet controlled.

Which brings us to yesterday’s universally expected decision by the Reserve Bank to leave their official cash rate unchanged at the 5.5% level they took it to back on May 24.

The RB noted signs of weakness in the world economy and easing capacity pressures in New Zealand. But they also noted a risk that in the short-term the pace of growth in the economy and inflation do not slow as quickly as is needed.

Hence, they feel they need to keep interest rates at restrictive levels. Now, we sit and wait for more data.

Specifically, we will watch not just growth indicators for the economy but the pace with which business pricing plans ease off and data on changes in the pace of wages growth – something which the RB noted they have a lack of up to date data on.