Demography group Informed Decision projects that Australia’s population will grow by 7.4 million by 2041, requiring two million additional homes.

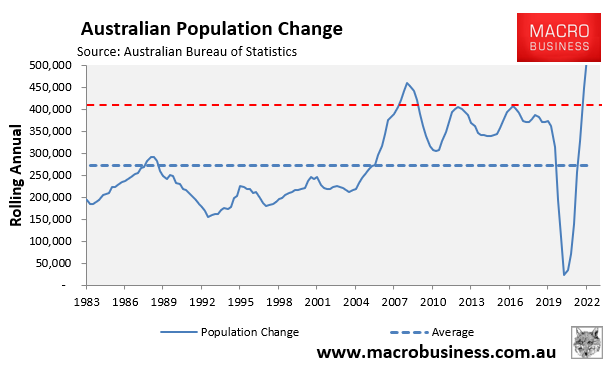

That’s 410,000 people a year for 18 years, which is around 90,000 more than the 318,000 average annual population growth this recorded this century (see red line below).

It took Australia 23 years to grow by 7.4 million people this century. But these projections have Australia growing by the same amount in just 18 years.

So, the nation’s population growth is forecast to be even more aggressive than the break-neck growth recorded so far this century, which has crush-loaded everything in sight: housing, infrastructure, the environment, and living standards.

Well over half (4.6 million) of this growth will be in Sydney (1.2 million), Melbourne (1.6 million), Brisbane (1.0 million), and Perth (800,000).

Anne Flaherty, economist at PropTrack, warned that “the plan to house Australia’s growing population is completely unrealistic”.

If anything, the rate of housing supply going forward will be less than in the recent past for a myriad of reasons.

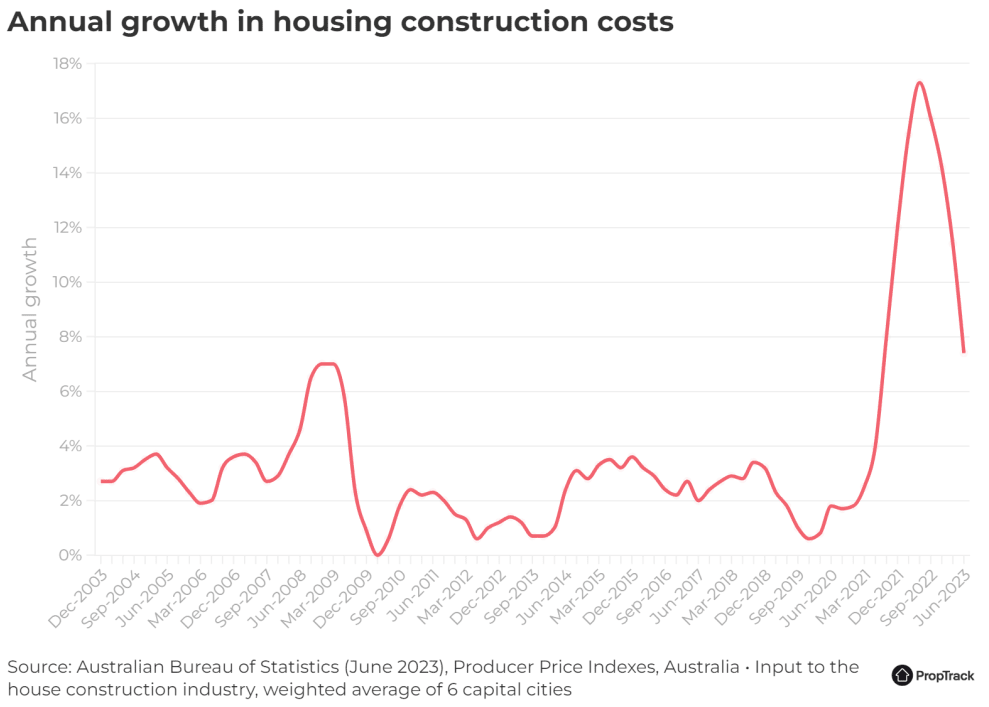

“Firstly, it has never been more expensive to build a new home. The cost of building inputs into housing construction have surged in recent years and grown at the fastest rate seen since the 1970s”, says Flaherty:

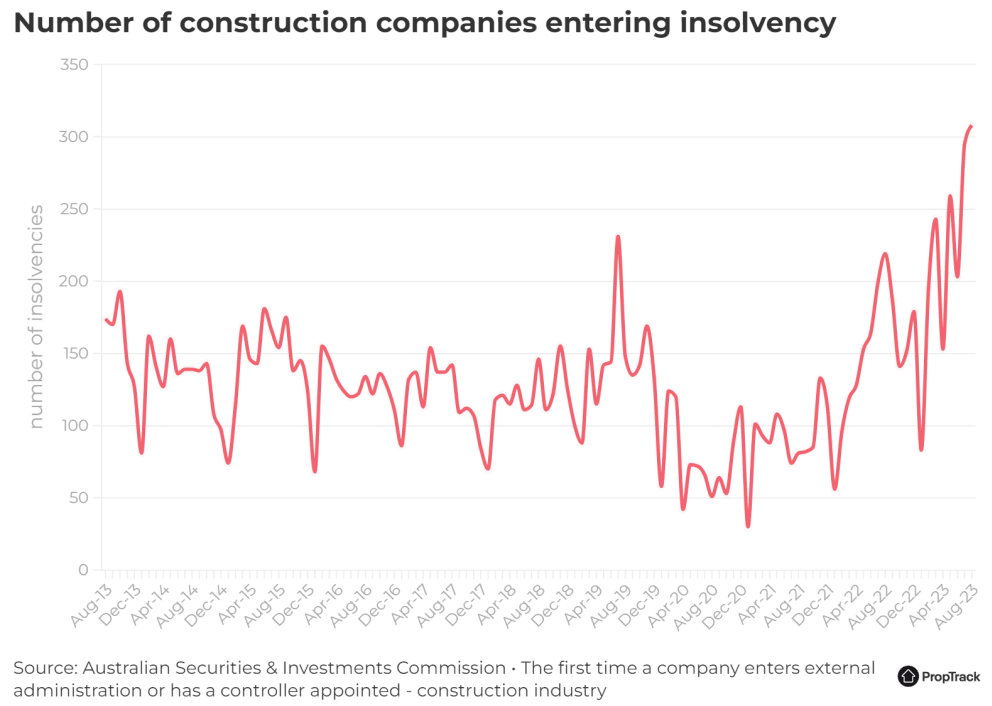

Second, “the near unprecedented speeds at which costs have increased have dealt a savage blow to builders” with “a total of 2,213 construction firms entered insolvency, up 72% from the previous 12 months”, last financial year:

Third, there is “increased hesitation to buy new, due to the higher perceived risk”.

“Back in 2020, 45% of those looking to buy a property felt confident purchasing off-the-plan, according to realestate.com.au’s Property Seeker Survey. This year, that share fell to 36%”.

“Similarly, the proportion of buyers who felt confident buying a newly built property fell from 60% to 55% between 2020 and 2023”.

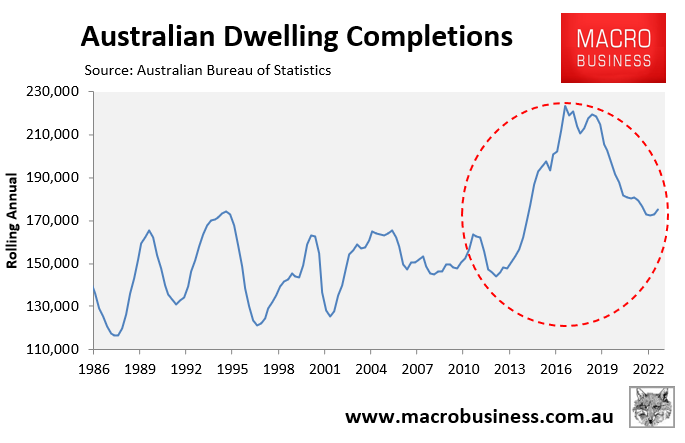

Fourth, “the development of so many homes over such a short period would be unprecedented. The government’s goal of delivering 1.2 million new homes in five years implies the completion of 240,000 dwellings per year”.

“Market conditions and cost pressures aside, at no point in history has Australia succeeded in delivering new housing at this speed. The highest number of dwellings ever completed over a 12-month period was 224,000, which occurred over the year ending March 2017”.

“And given the average number of annual dwelling completions was 191,000 over the past 10 years, this was well out of the ordinary. Last year, development activity fell below the 10-year average level, with 173,000 new homes completed”.

Finally, Anne Flaherty argues that declining dwelling approvals indicate that construction levels are likely to move lower. And this means the housing shortage will only worsen:

“This year, approvals for new dwellings have reached the lowest levels seen in over a decade. While approvals did rise 7% between July and August, they remained 22.9% down from the same month last year”.

“With population growth booming, this slowdown in the development of new homes could not be worse timed. Australia already has a critical shortage of housing and, if something doesn’t change soon, it will only get worse”.

Australia’s structural shortage of housing is the direct result of nearly 20 years of excessive immigration, which this year hit new heights and is officially projected to be stronger going forward.

If the Albanese Government genuinely wanted to end the nation’s housing crisis, it would moderate immigration to a level that is below the nation’s ability to supply housing and infrastructure, not the other way around.

Governments and housing analysts must stop pretending that a ‘lack of supply’ is the problem and address the immigration elephant that is trampling the housing market and Australian renters.