Dr Jane O’Sullivan from the University of Queensland gave a brilliant presentation rebutting the analysis contained in the 2023 Intergenerational Report (IGR), which was released by the Australian Treasury last month.

Below is the transcript with key slides. The full video presentation can be watched below.

Transcript:

My interest in Immigration is about its impact on the size of Australia’s population.

Growth is simply not sustainable, so one day it has to stop. And the sooner and lower it stops, the more resources we have per person and the less environmental damage we do.

Our world is facing an escalation of crises, from climate change and biodiversity loss to increasing hunger and running out of water. All these crises result from too many people demanding too much from our natural environment. We’ve lost 70% of wild animals in the last 50 years – humans alone make up a third of the mass of terrestrial mammals and our livestock makes up nearly the other two thirds – only 4% are wild animals.

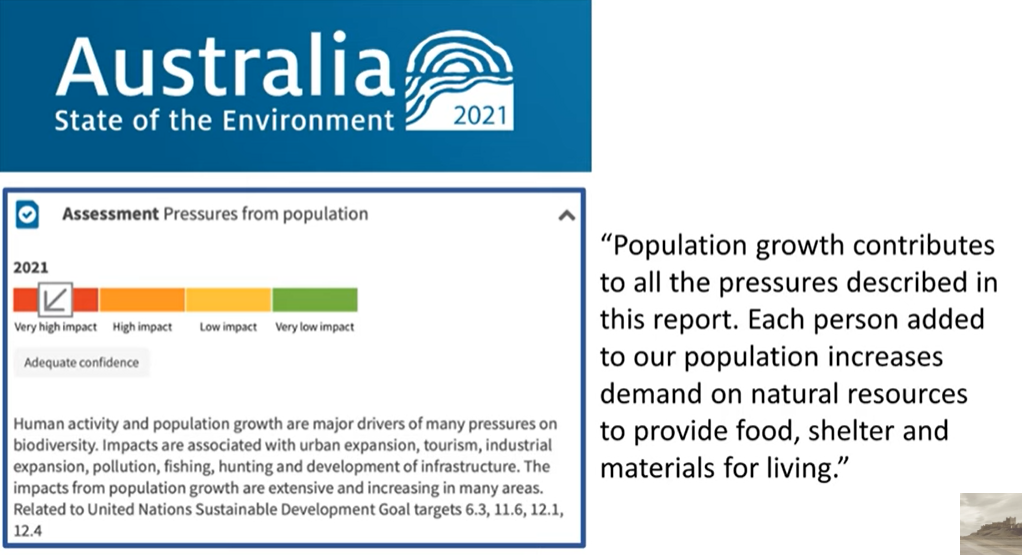

In Australia, the latest State of the Environment report lists population growth as a very high impact driver of environmental damage. It says “population growth contributes to all the pressures described in this report.”

Just last week, 48 more plants and animals were added to our threatened species list.

When Treasury decides our immigration quotas, I don’t think they think about how much we rely on the natural environment, and how vulnerable that relationship is. Australia usually produces enough grain to feed about 60 million people, but in a drought year, it might be only enough for 30 million people.

With more climate change, it could become much less. So in a very few years from now, we could be food insecure.

Our major cities already rely on desalinated seawater to supply enough water. That comes at a huge cost and a huge environmental footprint. It’s crazy to plan all this population growth without knowing where the food and water is coming from.

And yet, there are people who think the solution to everything is adding more people.

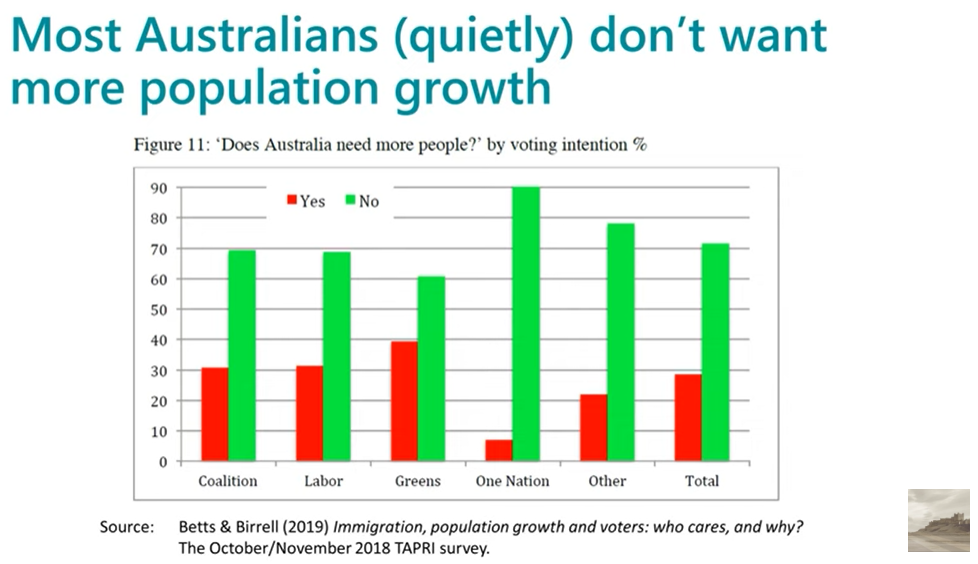

The majority of Australians don’t agree. Survey after survey shows that two thirds of Australians don’t want further population growth. It’s a majority across the political spectrum, even among Greens voters.

Most of the rest only want growth because they believe the scare campaigns about having nobody to care for them in their old age. Absolutely nothing about the quality of life in Australia is improved by increasing our population.

Australia is growing much faster than most other developed countries. The OECD average is about 0.4% per year, but we’ve been growing by about 1.5% a year.

Our growth was tapering off in the 1990s and people then assumed it would stabilize around 23-25 million.

But in the early 2000s, the Howard and then Rudd governments massively ramped it up, with Treasurer Costello’s call to have more babies – “one for mum, one for dad and one for the country” – but mainly by tripling our immigration rate.

We had a short lull during the pandemic, but we’re making up for it this year with around 2% growth.

It isn’t xenophobic to say we need to have a sustainable level of immigration.

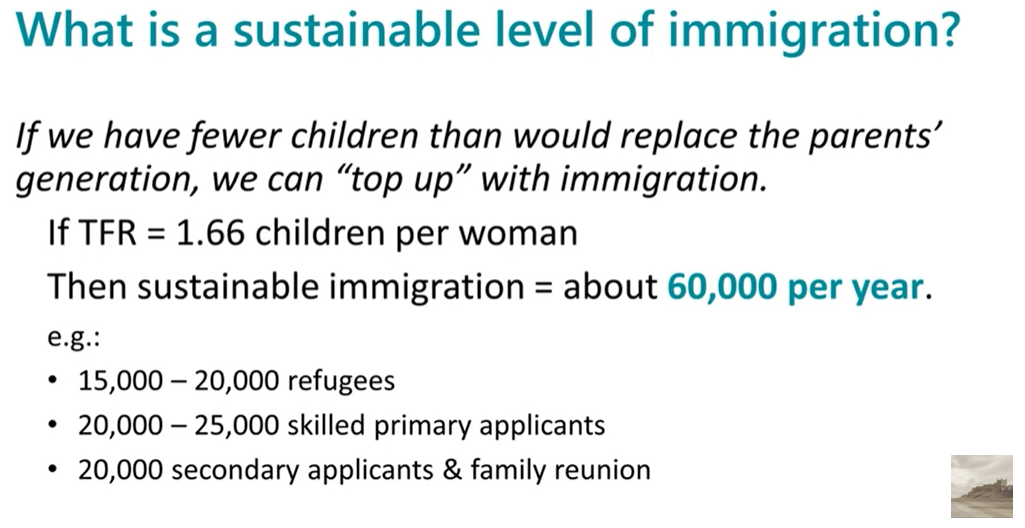

And what that means is limiting the immigration to the level that just makes up for below replacement fertility.

What that means is limiting immigration to a level that just makes up for below-replacement fertility – that is to say, because Australians are having fewer children than would replace the parents’ generation, we can have a modest inflow of new migrants without it causing long-term population growth.

Low birth rates are a good thing. We could even reduce the population gradually if we chose to have less immigration than needed to top up, and that would be even better for the environment and climate change and housing affordability.

So, how much immigration is sustainable? It works out at around 60,000 per year Net Overseas Migration. That’s around the average flow we had through the 20th Century.

When you factor in approximately 20,000 Australians who emigrate permanently each year, that allows maybe 80,000 new immigrants. And that’s more than enough to cover our refugee intake and fill real skills shortages and allow real family reunions, but not chain migration.

So I’m not advocating a closed-door policy here at all.

But what we have been getting lately is around 230,000. That’s nearly as many new migrants as we have school leavers – an extraordinary level of competition for young Australians entering the job market and the housing market.

And it’s even harder for the new migrants. We know they end up being exploited in all sorts of low-skilled jobs because they find it very difficult to get work in the jobs they are trained for.

In most countries, you have to get a job offer before you can apply for a work visa, but we mostly bring in people with no job to go to. On average, they earn less than the average Australian and they have lower workforce participation.

Because of that, they add to demand for skills more than they add to the supply. After nearly 20 years of running the world’s biggest so-called “skilled migration” program, claims of skills shortages are louder than ever.

But a recent government report says: “Constant growth supports our prosperity”.

And the Home Affairs website says, “Migration has been essential to helping Australia become one of the most prosperous countries in the world.” And we all thought it was minerals that did that – with fewer royalties the more people we have.

There is no quantitative analysis behind these statements. They’re just used to quell public opposition to high immigration.

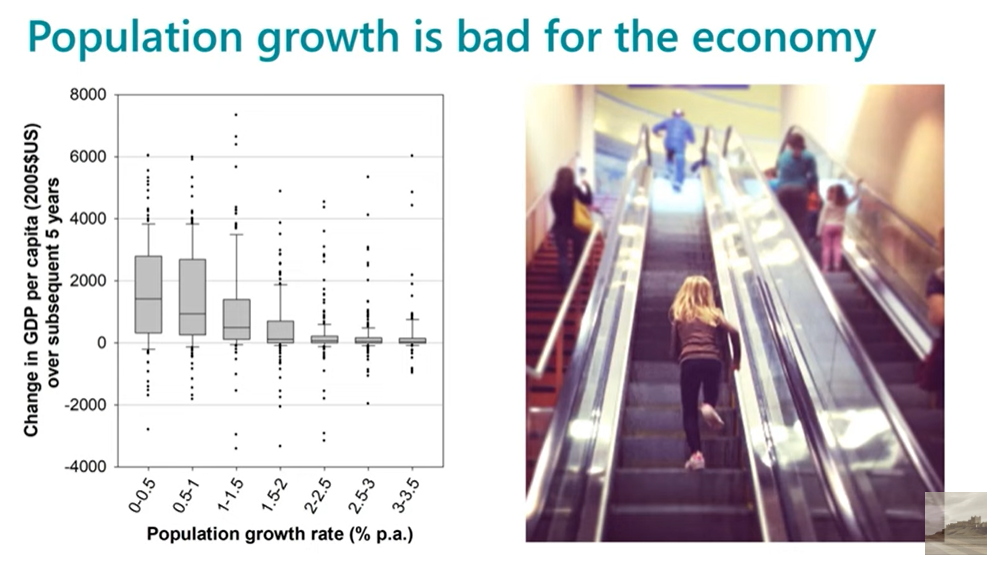

I want to show you this chart, which is data from all countries in the world, with a data-point for each five year period from 1960 to 2010:

This is casting the widest net I could, to see what sort of relationship there is between population growth and improving prosperity.

So, across the bottom, you have population growth rate, and vertically, you have the increase in GDP per capita over five years.

And what we see is that countries growing their population at 2% or more have generally failed to show any enrichment.

The slower the growth, the better they have done. Australia has been growing around 1.5% a year for the decade before the pandemic – you know, that decade when productivity growth tanked and wages started falling behind cost of living.

And, by the way, we had the OECD’s highest youth underutilisation rate. And the business lobby wants us to grow even faster. That seems pretty foolhardy to me.

I like to explain this as like trying to run up a down escalator. If it’s going too fast, despite your best efforts, you end up going backwards.

If the population is growing at 1.5% per year, we have to build an extra 1.5% of everything – not just houses and shops and workplaces but schools, hospitals, power stations, roads, sewers, prisons, you name it – just to avoid going backwards.

Adding 1.5% of all infrastructure and durable assets costs around 10-11% of GDP. All that spending adds to GDP, but it takes away from what we can spend on making things better and enjoying life.

And it all has environmental impacts. If we slow the escalator down, for the same amount of effort, we start getting ahead. The slower it goes, the more of our effort is for betterment, rather than biggerment.

Treasury, apparently, doesn’t get this. They proudly say high immigration is preventing Australia from having a recession. Except that we do have a per capita recession which is what they should care about, and it’s made worse by population growth.

But Treasurer Jim Chalmers says GDP growth is “sturdy”. It’s just not growing faster than the population, so everyone’s slice of the pie is getting smaller.

This is like the government saying, “we know you’re getting poorer, but it doesn’t matter because we aren’t.” Do babies and bathwater come to mind? Don’t they have a mandate for betterment, rather than biggerment?

There are some people who do benefit considerably from population growth. They want to privatise the benefits and socialise the costs. They include:

- the property industry, who want housing to become increasingly unaffordable for ever.

- The business lobby, who want to suppress wage growth and add customers.

- The university Vice Chancellors, for whom international students are cash cows, despite them dragging down standards in our universities.

- And migration agents, some of whom are well-meaning, but most are running a lucrative business in visa rorts.

We know they have enormous influence on government policy. Let’s be clear – if their profits depend on suppressing wages and inflating housing costs and flattening native habitats, then their interests are not the national interest. They are not the pillars of our economy, they are parasites on it.

Treasury’s Intergenerational Report is the main marketing tool for the Big Australia policy. It was introduced in 2002 to make everyone scared of an ageing population and welcome a massive increase in youthful migrants.

The growth we’ve had over the past two decades is beyond the wildest dreams of the Business Council in 2002. But they’re never satisfied. This year they want to lock in immigration as a percent of population, so it automatically increases as the population increases.

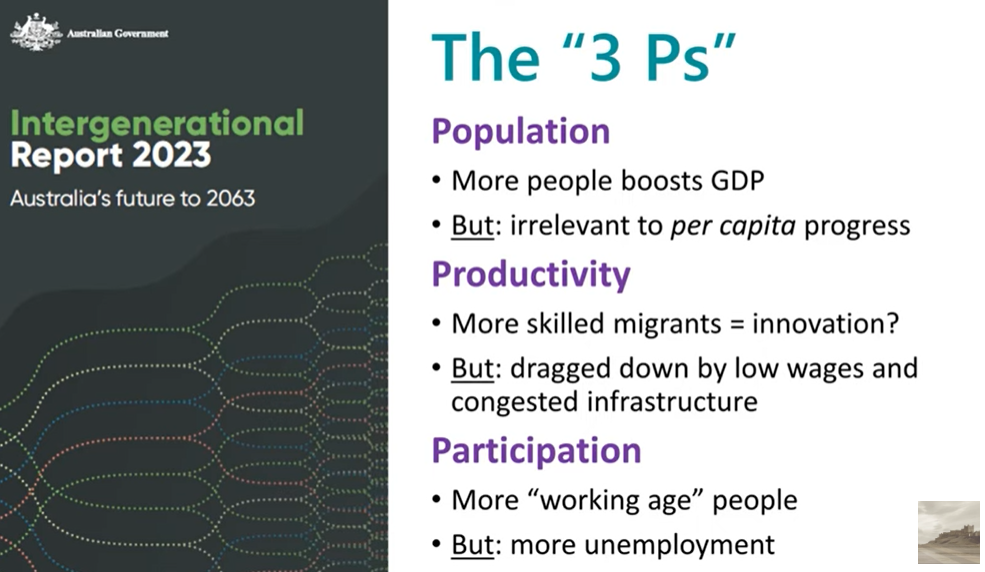

A favourite theme of the Intergenerational Reports is “the 3 Ps: Population, Participation and Productivity”.

But if you think about it for two seconds, what we want is per capita prosperity, so the “Population” factor cancels out.

We can’t have more people per capita. And we shouldn’t even want per capita growth if it means the rich getting richer at the expense of the poor.

Then there’s “Productivity”, and the theory goes that skills shortages are holding us back, so more skilled migrants will make us more productive.

But there is no real evidence for this. What we have seen is more people doing low-paid, menial work with low productivity, and this drags the whole national productivity down. That’s on top of the drag caused by overcrowded infrastructure causing delays.

But what they’re really on about is the “Participation” term: the proportion of people who actually participate in the paid workforce.

This is the idea that, if there are fewer people of “working age” compared with retirees, we’ll have a smaller economy. This is the main thrust of the ageing population scare.

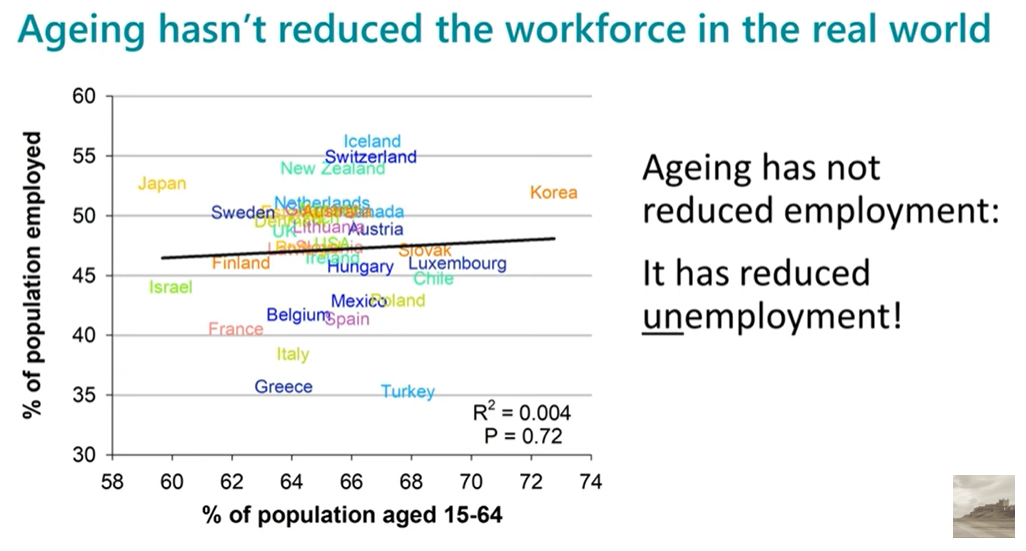

Again, there is no evidence for this in the real world. This chart shows all the OECD countries, with their proportion of “working age” people compared with their proportion of people employed. There is a complete lack of any correlation.

The countries with more retirees don’t have fewer workers. This is because, as the labour market tightens, unemployment goes down and workforce participation in any age group goes up, so the workforce stays much the same.

It means more opportunities for disadvantaged job seekers, like people with disabilities, and better pay and conditions if that’s what it takes to keep good employees in a competitive market. So the GDP is not lower, and most people are better off, with a more equal income distribution.

But the big profits for the super-rich aren’t there if they can’t exploit workers and if we don’t need to rezone more land and if they can’t over-charge for rent.

Economists’ models aren’t anticipating this because they don’t deal with labour demand at all, they just assume less labour supply means proportionally less jobs being done and taxes being paid. It’s simply not true – even in ageing countries, there is an oversupply of potential labour ready to fill jobs as the labour market tightens.

Then, there is all the catastrophism about pensions and aged care.

The Treasurer has been going on about the care sector increasing from 8% to 15% of GDP by 2063, which the media presents as being due to ageing.

But the IGR’s own figures say ageing only accounts for a 1.5% increase. But we’re using more than 10% of GDP to build the infrastructure to accommodate population growth.

Admittedly, only a quarter of that is public money, and little of it comes out of the Federal budget, but however we pay for it, it costs us. The public infrastructure alone costs upwards of $120,000 per person we add.

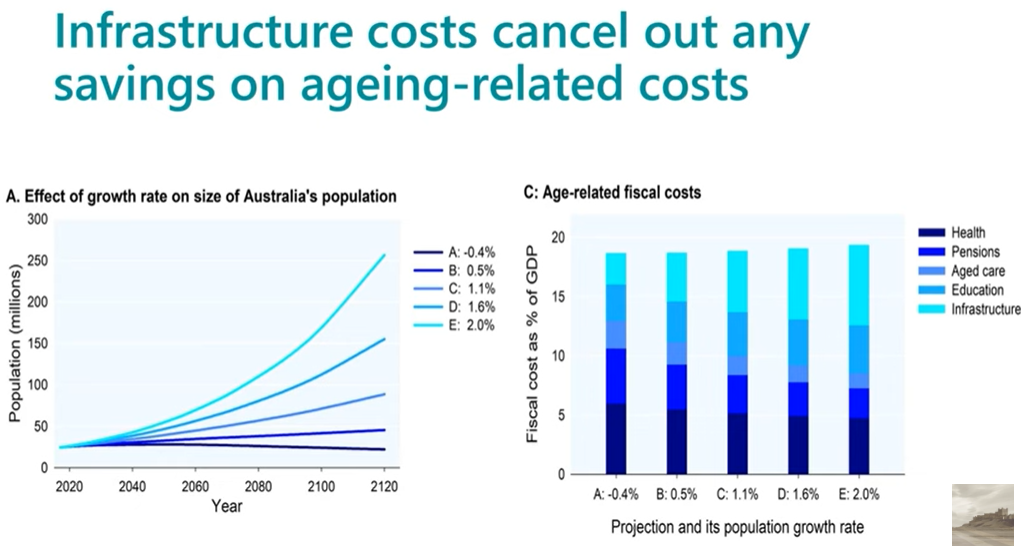

These charts are from a study I did trying to find out how the public costs of population growth stack up against the cost of ageing.

I ran several projections of Australia’s population with different growth rates, and looked at the proportions of elderly and working-age people in each, and used today’s age-related costs.

And what I found was that the extra infrastructure and education costs from a rapidly growing population completely cancel out any benefit from a smaller proportion of retirees.

And that’s based on the costs over the past 50 years, not counting the massive increase in per capita costs as Australia’s overgrown cities resort to desalination plants and underground transport tunnels.

So population growth only looks good on paper, if you don’t bother adding up the costs.

So, to summarise:

- Ending population growth sooner rather than later would greatly improve prospects for Australia and the World.

- Population growth is not only bad for the environment, it is bad for the economy.

- None of the reasons given for Big Australia policies hold water.

- The true motives are to suppress wages and boost house prices.

As the economist, Kenneth Boulding, once said, “Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

And finally, I just want to give a quick plug for Sustainable Population Australia’s discussion papers, which are available online if you’re looking for further detail in well-referenced sources. I look forward to our discussion.