Last week, AMP chief economist, Shane Oliver, told the AFR Housing Summit that Australia’s housing shortage will only be solved if net overseas migration is lowered to a level commensurate with the nation’s ability to supply new housing:

“If you’ve got more demand in terms of people that need a home and not enough supply, then prices will go up. So the way around that is to peg the level of immigration you have each year to the ability of the housing market to supply new homes”.

Shane Oliver has now published a research note explaining how high levels of net overseas migration is behind Australia’s housing shortage and why immigration levels need to be cut to give Australia any chance of solving the housing shortage.

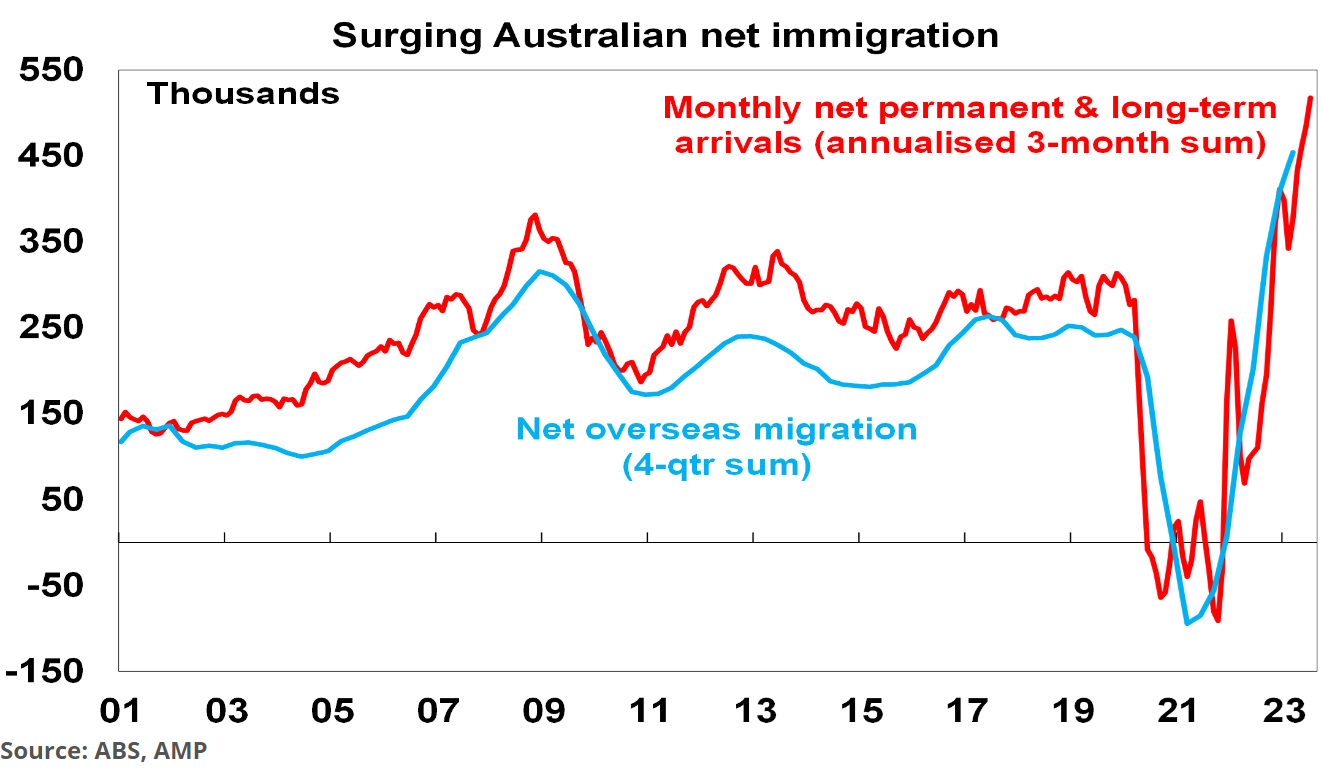

The next chart from Oliver shows that Australia is on track for 500,000 net overseas migration in the 2022-23 financial year, which would be 100,000 more than forecast in the May federal budget:

Oliver notes that “what really counts for living standards is per capita GDP (and it’s going backwards) and surging immigration is making the housing shortage worse”.

Oliver argues “the role of immigration in the demand/supply mismatch is critical” to Australia’s housing woes:

“There has been a fundamental failure of housing supply (for lots of reasons ranging from development controls to capacity constraints) to keep up with a surge in demand for housing that started in the mid-2000s with rapid population growth. The concentration of people in just a few coastal cities hasn’t helped”.

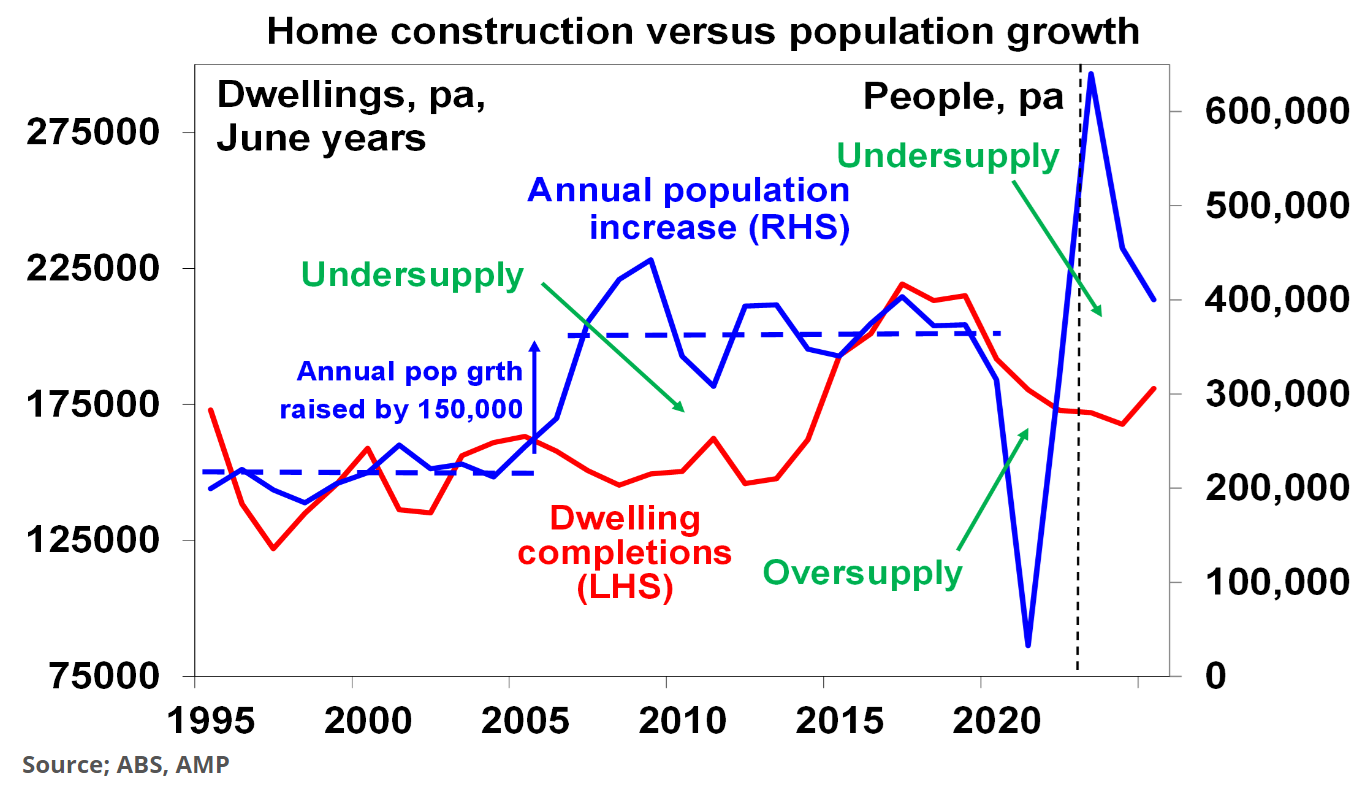

“Starting in the mid-2000s annual population growth jumped by around 150,000 people on the back of a surge in net immigration levels – see the blue line in the next chart. This should have been matched by an increase in dwelling completions of around 60,000 per annum but there was no such rise in completions until after 2015 leading to a chronic undersupply of homes – see the red line”.

“The unit building boom of the second half of last decade and the slump in population growth through the pandemic helped relieve the imbalance but the unit building boom was brief and a decline in household size from 2021 resulted in demand for an extra 120,000 dwellings on the RBA’s estimates. The rebound in population growth has taken the property market back into undersupply again”.

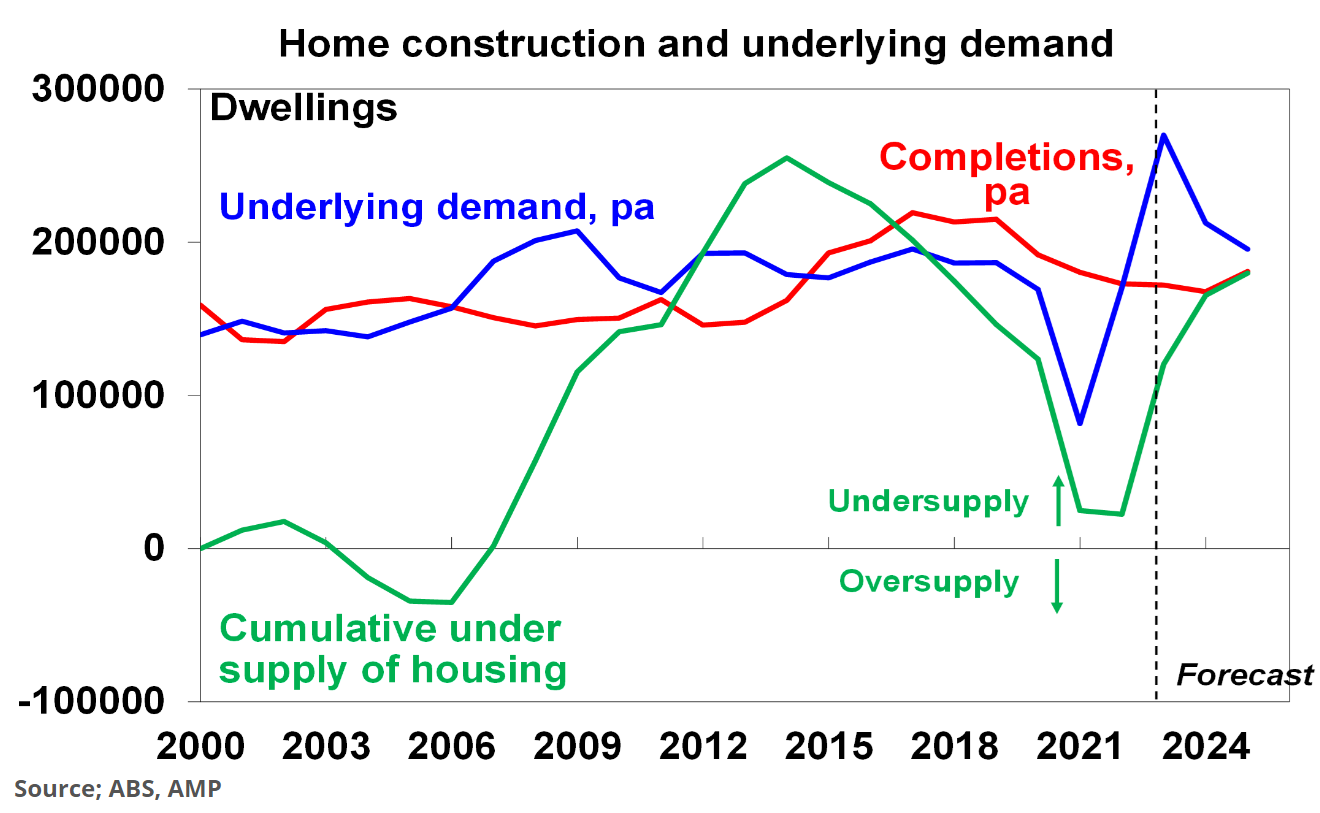

The next chart from Oliver illustrates the immigration-induced undersupply. It shows underling demand (blue line) and supply (red line) for homes and the cumulative undersupply gap between them (green line):

“Up until 2005 the housing market was in rough balance. It then went into a massive shortfall of about 250,000 dwellings by 2014 as underlying demand surged with booming immigration. This short fall was then cut into by the unit building boom and we nearly got back to balance in the pandemic”.

“A rebound in underlying demand on the back of this year’s immigration surge and weak completions has now pushed the shortfall back up to 120,000 and by mid next year it will be around 165,000. This makes no allowance for the pandemic induced fall in household size which could take the shortfall up to around 285,000”.

“Meanwhile the surge in immigration has pushed underlying demand for homes to an average 220,000 dwellings over the three years to 2025. But thanks to rate hikes and capacity constraints dwelling completions look like averaging around 175,000 which means a new shortfall each year of about 45,000 dwellings adding to the already existing shortfall”.

“The housing shortfall is confirmed by record low rental vacancy rates”.

Oliver concludes that immigration levels need to be lower if Australia has any hope of solving the housing shortage:

“The surge in immigration is adding to the already large supply shortfall and threatening to swamp the extra supply commitments governments are making”.

“It’s impossible to escape the conclusion that immigration levels need to be calibrated to the ability of the home building industry to supply housing. This is critical”.

“Current immigration levels are running well in excess of the ability of the housing industry to supply enough homes exacerbating an acute housing shortage and poor housing affordability.

Our rough estimate is that if home building supply capacity is 200,000 dwellings a year (as we managed in the five years to 2022) then immigration levels need to be cut back to 260,000 from around 500,000 now”.

“But if capacity is just 180,000 dwellings pa or we want to reduce the accumulated supply shortfall by say 20,000 dwellings a year then immigration should be cut back to near 200,000 people a year”.

I will add that immigration levels also need to be calibrated to Australia’s ability to provide infrastructure and secure water supplies, as well as the environment’s carrying capacity.

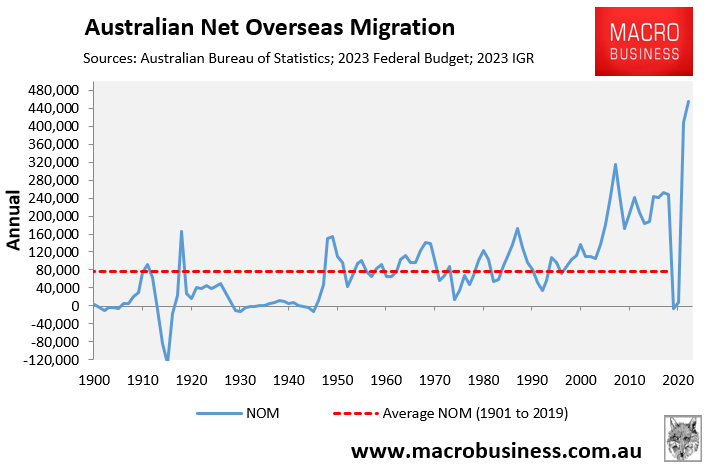

When housing, infrastructure, water and environmental issues are all taken into account, it become patently clear that net overseas migration levels should be set closer to the historical post-war average of around 100,000 per year:

These immigration levels worked well for Australia in the 60 years following the Second World War. By contrast, the high immigration levels since the mid-2000s have not worked out well.