University degrees have become tickets to employment, but not necessarily success, according to an Australian study by the Mackenzie Research Institute at Melbourne’s Holmesglen Institute.

While the highest-paid and best jobs are exclusively held by the university-educated, their share of low-paying work is also rising.

This frequently comes at the expense of those who hold only diplomas and trade certificates, who then crowd-out workers with minimal or no post-secondary credentials.

Former executive director of the National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Dr Tom Karmel, said the findings highlighted concerns about the “never-ending push” to have more people hold degrees.

“There’s no doubt that the occupations where people need degrees are growing faster than others, but the rate of credential growth has been so much greater than that”, he said.

“Credentials are becoming increasingly important even in lower paid jobs”.

“Is it skills deepening or is it really just blatant credentialism? It’s probably a bit of both. If everybody had a degree, a degree would be useless”, he said.

Dr Karmel used data from Australia’s 2011 and 2021 censuses in his analysis.

Over that decade, the number of people with postgraduate degrees more than doubled, rising from roughly 500,000 to almost 1.1 million, and their percentage of the workforce increased from 5% to 9%.

There are now 3.1 million workers with undergraduate degrees, comprising 26% of the workforce.

By 2021, roughly 2% of labourers, machine operators, and technicians, 3% of salespeople, and 6% of clerical and administrative workers had master’s or PhD degrees.

In all of these professions, the proportion of bachelor’s degrees was roughly four times higher.

The situation will only worsen under the Albanese Government’s Universities Accord interim report, commissioned by Education Minister Jason Clare.

This report recommends a higher education attainment target of 55% by 2050, which would require an additional 300,000 domestic undergraduate students by 2035 and 900,000 by 2050.

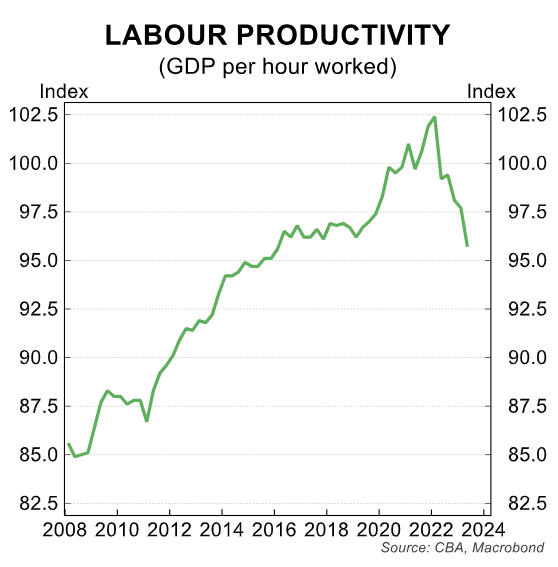

One of Australia’s biggest economic paradoxes is that while we have a record number of university graduates, productivity growth stinks and there are never-ending “skills shortages”:

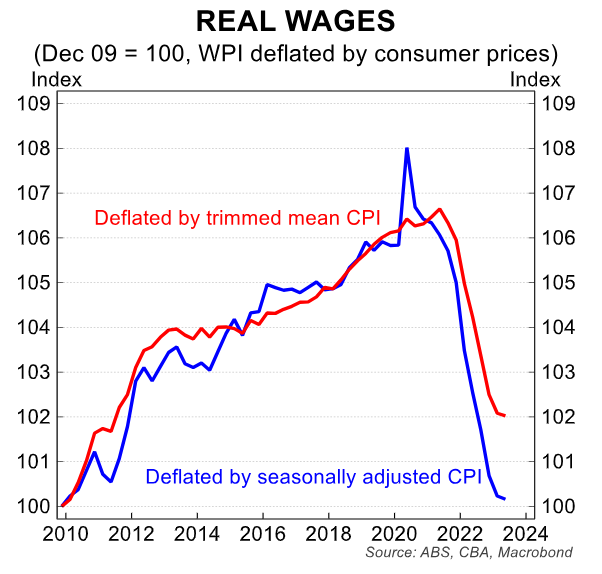

Australia’s real wage growth has also declined during the great university boom:

What is the point of having 55% of Australians between the ages of 25 and 44 gaining a bachelor’s degree or higher?

Most jobs require a university degree, not because of any specific demand or skill developed, but because employers use it as a ‘signalling’ tool to screen job applicants.

This “credential inflation” has expanded university attendance while contributing next to nothing of benefit to the economy or society.

The increasing number of individuals attending university has devalued it because practically everyone today holds a degree.

Even entry-level jobs now require a university degree, despite the fact that these jobs were previously performed well by people with only a high school diploma.

As a result, public funds have shifted away from vocational training and TAFE, which have fallen out of popularity. This has created chronic skill shortages in several fields.

Let’s be real. Universities have evolved into self-serving behemoths driven by profit, graduating far too many students who would have been better off pursuing a vocational course.

Policy priorities must be adjusted.

To begin with, university admissions rules should be tightened for both domestic and international students. Governments should also expand VET and TAFE financing.

Prioritising a university education over trade school or vocational training was never a good economic or societal decision.