This is getting embarrassing. Albo is crawling to China as the rest of the world withdraws at a sprint:

The AFR sent its resident China apologist, Professor James Curran, to sprinkle petals on Albo’s path to Beijing:

Bloomberg now predicts China’s growth rate, which was 5.5 per cent in the first half of this year, will to slow to 3.5 per cent in 2030, 2.8 per cent in 2040 and close to 1 per cent in 2050. No wonder there is concern for the world’s second-largest economy.

But the open question of whether this slowdown is structural or cyclical, and whether therefore we have arrived at an inflection point, is being overtaken by a powerful narrative already ascendant in much Western commentary.

It is driven primarily by the ideological imperative of a “new Cold War” framework in which China’s political system, especially a stubborn and rigid leadership, is presiding over the demise of the China “dream” – to the West’s advantage.

This mood blends American triumphalism with liberal democratic instincts to virtually celebrate China’s stiff economic headwinds. The head of the Petersen Institute for International Economics, Adam Posen, typifies this approach, likening China to Venezuela and largely attributing its current crisis to the “original sin” of its authoritarian political system.

It is not a “mood”. It is a fact. It is structural, not cyclical. And it is largely thanks to the Chinese illiberal system.

Professors of history need to understand development economics.

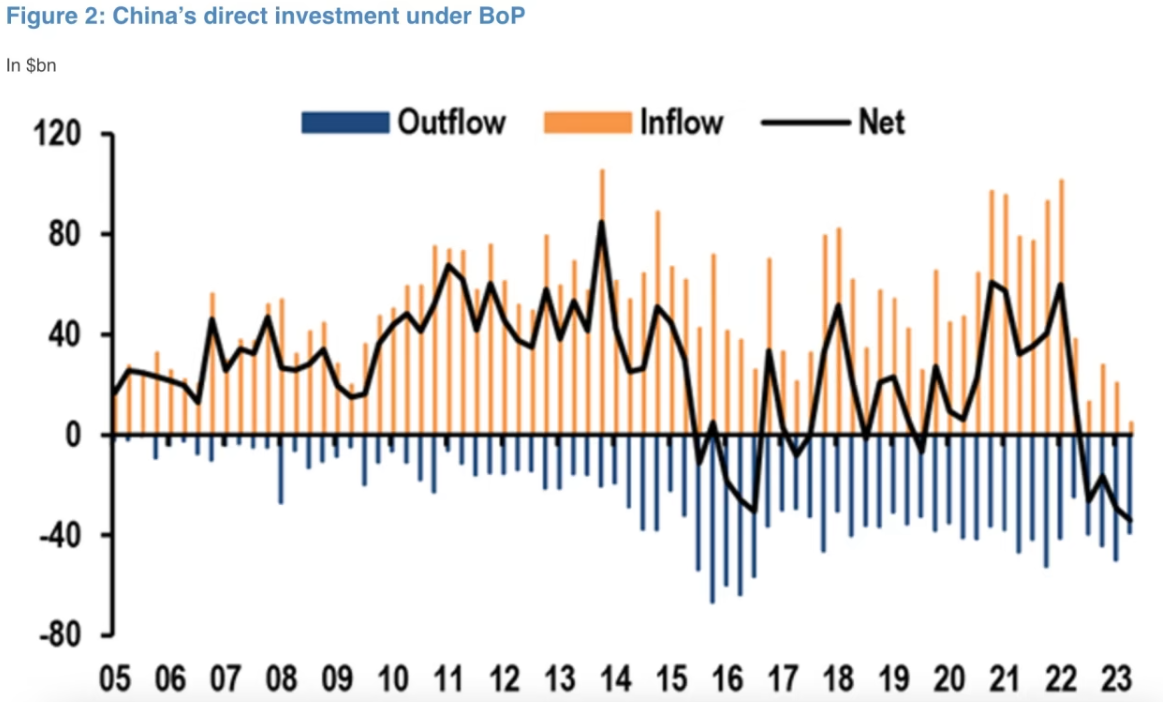

China has boomed for thirty years because it embraced the liberal policies of the West. Liberalisation unleashed the basics of development economics, such as trade, foreign capital inflows, the demographic tailwind, urbanisation and productivity potential.

All of these are now in full reverse, along with liberalism.

This need not be fatal to growth. But it is if your political system disqualifies reform.

For instance, China could manage the bad debt crisis emanating from its urbanisation overreach via more liberalisation. If it accelerated resolution in bad banks and writedowns, coupled with large reforms to shift income and wealth from SOEs to households, a sharp recession would be followed by an equally large recovery.

Growth would be lower than in the past but still good enough to continue China’s rise.

But the CCP cannot bear this. Such reforms also transfer power to households, denuding the Party of money and influence. So it’s a non-starter.

Instead, the Party is doing what all such systems do—creating a police state to manage the anger that rises with stalled living standards.

The result is a structural doom loop with the bellicosity of the state. The more growth slows, the angrier the state response, the more growth slows. If it cannot manage insurrection internally, it will eventually declare war externally, ending its economic power.

I was able to predict all of this years ago because a basic understanding of history makes it obvious. Only liberal systems are flexible enough to transition from a developing, centralised investment model to an advanced, decentralised consumption model.

See Chile versus Argentina. South Korea versus North Korea. Thailand versus Myanmar. Singapore versus Indonesia. All have idiosyncracies, but the principle holds.

The only crisis of ideas underway is among Chinese apologists who have forgotten that it only boomed because it became more like the West.

Now, it is getting less so, and the end writes itself.