Victorian Premier Dan Andrews this week announced a fantasy plan to build 80,000 homes a year for 10 years.

The 40-page housing policy statement outlines the government’s plans to speed up dwelling approval times, rebuild the state’s existing social housing towers, and open up land in established suburbs in order to build 800,000 new homes over the next decade.

The 800,000 target hasn’t got a snowflake’s chance in hell of being achieved.

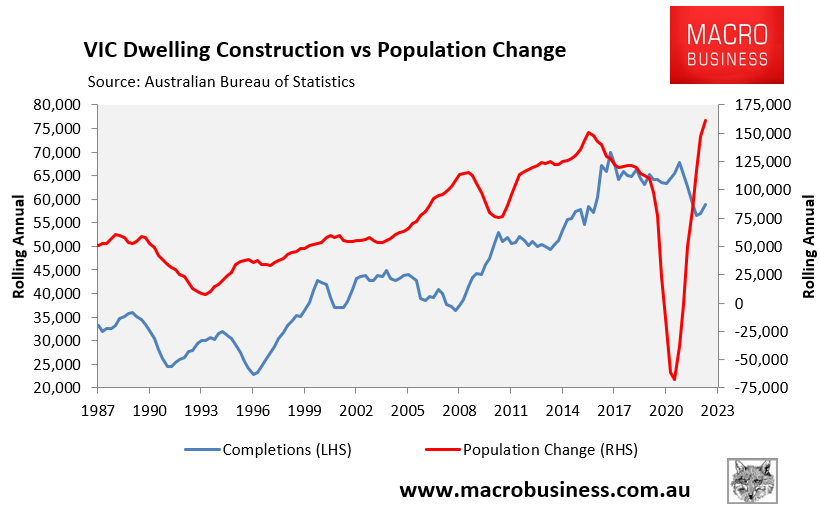

As illustrated in the next chart, Victoria’s record for dwelling construction was 69,972 in the year to September 2017:

This level of construction was achieved when interest rates were far lower and before the hyperinflation in materials costs and widespread builder failures experienced over the past 18 months.

Therefore, targeting 80,000 homes per annum for a decade straight is pure delusion and spin on Dan Andrews’ part.

Moreover, the Victorian Government has embarked on a large infrastructure spend, including its $200 billion Suburban Rail Loop boondoggle, which has sucked construction workers away from the housing industry.

Consultancy RLB warns that Victoria will need an extra 50,000 construction workers to meet its home building target. This puts the state in competition with New South Wales and Queensland, which are also attempting to boost their construction workforces to boost housing supply and prepare for the 2032 Brisbane Olympics.

“Victoria has averaged to complete 60,000 dwellings per annum over the past decade. Increasing this to 80,000 over the next decade would require an additional 50,000 construction workers and associated professionals on top of the current workforce, which is already stretched”, RLB’s Oceania director of research and development, Domenic Schiafone said.

“It’s difficult to understand where these workers will be sourced, as any previous shortfall has been filled by interstate and overseas workers, but these regions are also under pressure due to surging activity”.

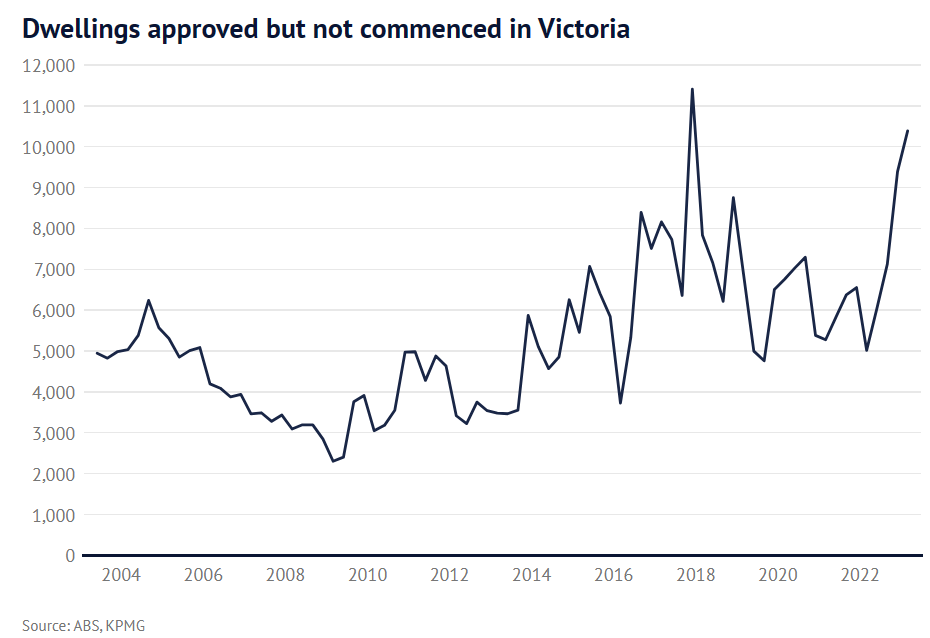

The notion that simply removing red tape and speeding up approval times will accelerate construction is also absurd.

Analysis provided to The Age by the Municipal Association of Victoria shows there are nearly 120,000 houses, townhouses and units that have been approved under Victoria’s planning laws on which construction has not yet begun:

In turn, this suggests that rigidity in “planning” is not the problem. Rather, supply-side bottlenecks like materials costs, high interest rates and labour shortages are preventing homes from being built. Or just as likely, developers are sitting on large numbers of approvals waiting for better margins.

“The evidence is clear … removing planning powers from councils is not going to fix the housing crisis because the current planning system is not where the problem is”, said Municipal Association of Victoria deputy president Jennifer Anderson.

Prosper Australia recently published a study of 25,000 sales in nine subdivisions, which discovered that after 9.5 years of production time, developers still retained 76.7% of their land bank unoccupied across all types of housing.

That is, even when councils approve something, developers hold it back in order to limit supply and bolster prices.

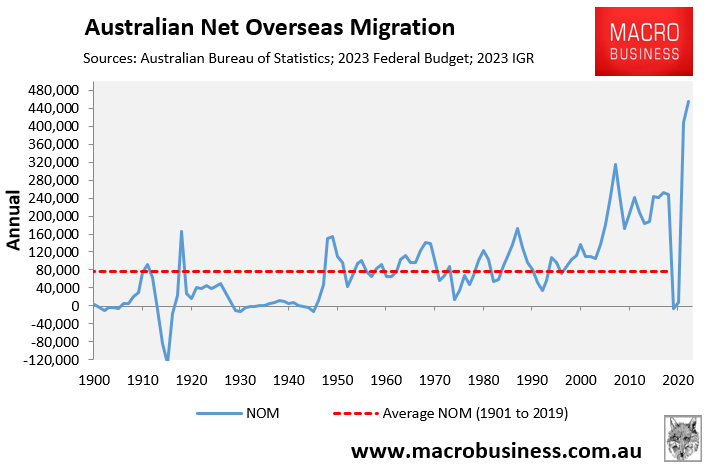

Let’s get back to basics: constantly feeding demand through extraordinary levels of immigration (population increase) will not solve the housing supply problem.

Reducing immigration to a sustainable level closer to the historical average is the first best answer to Australia’s housing crisis:

Doing so would put an end to the housing shortage and would eliminate the need to convert Australian suburbs into densely packed apartment towers.

Australians overwhelming oppose high levels of immigration.

No one voted for Albo’s giant 40.5 million-person Australia by 2063. Nobody wants their suburbs transformed into high-rise slums.