Goldman with a tidy note on the end of Chinese growth.

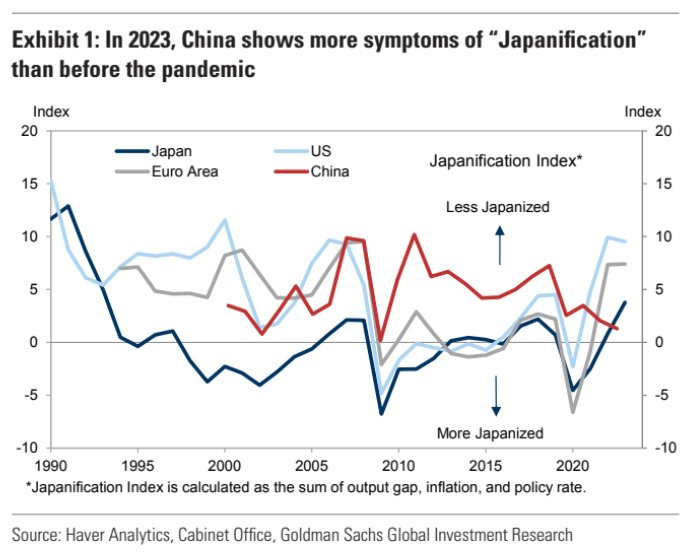

China’s sluggish growth, nearly non-existent inflation, and low nominal interest rates this year raise the question of whether China’s economy could undergo “Japanification” in the coming years. In this note, we revisit the China-Japan comparison, examine the question “what made Japan Japan” in the 1990s, and discuss policy remedies for China to avoid Japanification.

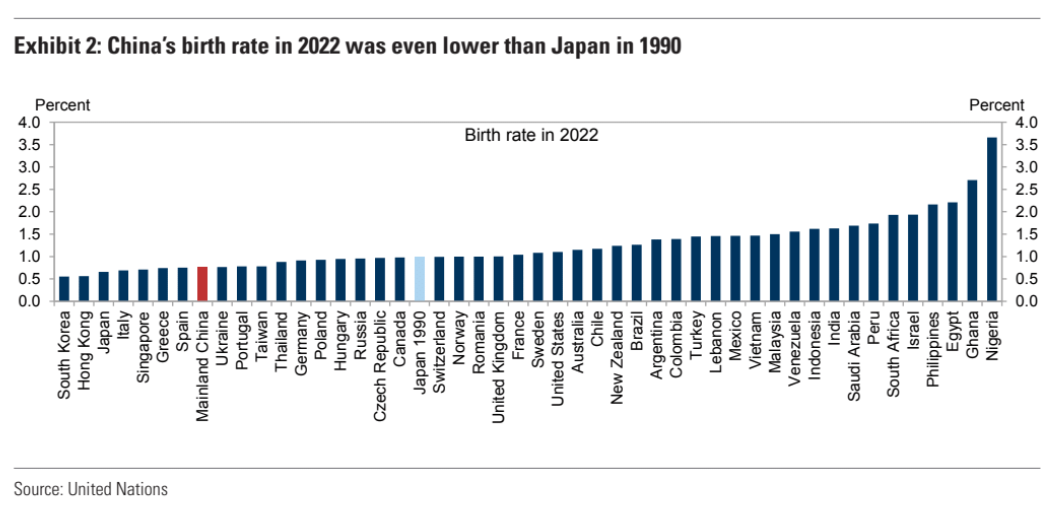

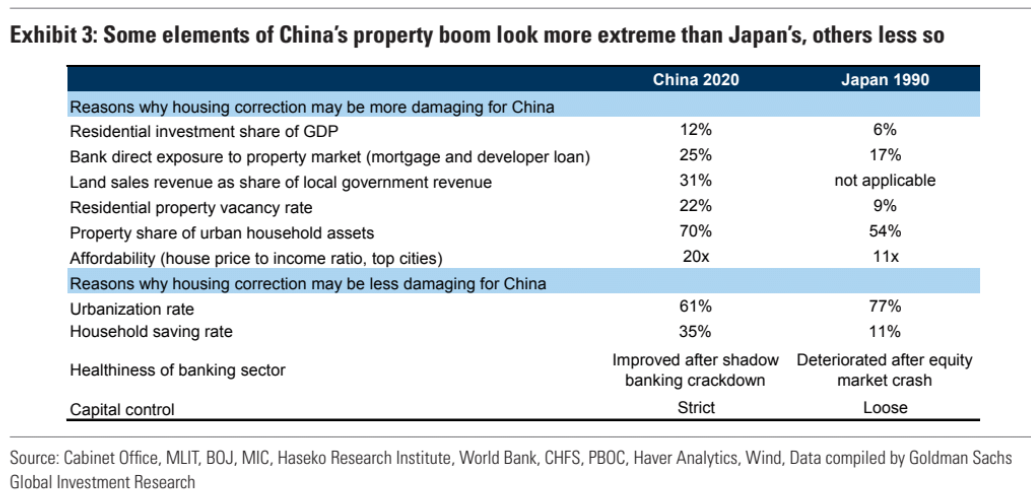

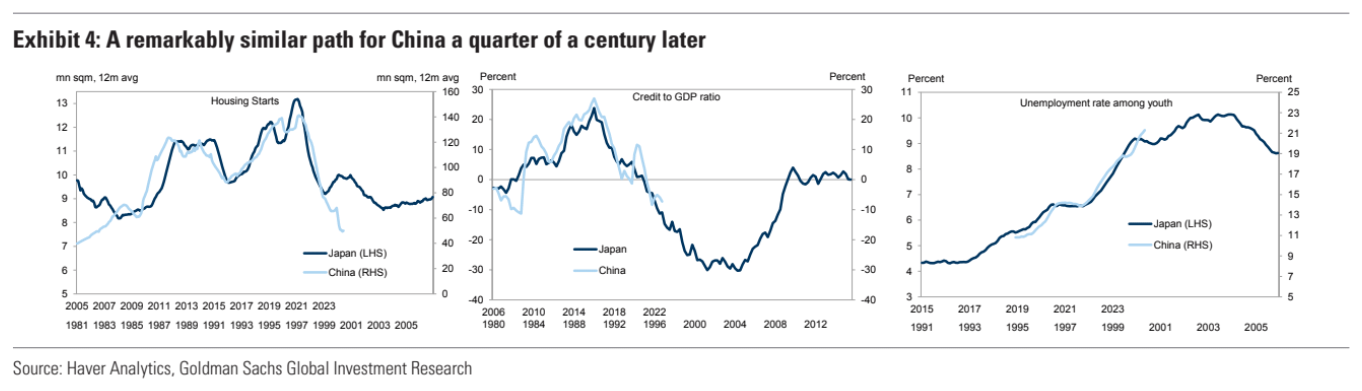

Along the two dimensions China is often compared to Japan, namely demographics and housing excesses, today’s China looks even more extreme than Japan in 1990 on certain metrics, with a lower birth rate, a higher residential vacancy rate, and more stretched house prices. On the other hand, the Chinese economy may be better positioned because of its lower urbanization rate, lower GDP per capita (and therefore more room for productivity growth catch-up), and the ability to learn from Japan’s experiences.

While important, demographics may not be the ultimate driver of “Japanification”. In Japan’s experience, it was the expectation channel that is the most crucial. Once the demographic and debt overhang backdrop combined with asset bubble burst and policy missteps triggered a sustained downward shift in longer-term growth expectations, households reduced consumption and businesses cut back on investment, and spot growth weakened, which further depressed the longer-term growth outlook.

Risks of Japanification appear to have emerged in China over the past year and a half. Investment by private companies has contracted, consumer confidence remains depressed, and forecasters have revised down China’s medium-term GDP growth projections notably. Given the importance of longer-term growth expectations as demonstrated by Japan’s experience, it would be critical for Chinese policymakers to circuit-break any sustained deterioration in growth outlook during its economic transition away from property/infrastructure investment. For example, accelerating the restructuring of troubled property developers and local government financing vehicles, and strengthening social safety nets to encourage household consumption can boost longer-term growth expectations.

Additionally, Japan’s experience suggests it is important for the Chinese government (1) to improve policy predictability and coordination to raise investment demand of private companies, (2) to avoid having commercial banks shoulder most of the NPL losses during the property deleveraging and local government implicit debt cleanup in order to protect their credit creation ability, and (3) to exercise great caution when implementing wage-cutting policies to prevent a wage-price downward spiral that could reset inflation expectations lower and make debt deleveraging excessively painful.

It’s good advice, but Xi Jinping will not take it:

- It means acknowledging losses and a taking big writedown to GDP. Xi does not do culpability.

- Xi derides any form of consumer support as “welfare”. Nor does he want the country brimming with rich households clamouring for freedom.

- Without real estate, consumption and centrally planned investment, Xi is forced to rely exclusively upon competitiveness for growth. That means a lower CNY and maybe wages, too. Though the closed capital account means it can only happen slowly unless it turns unruly.

All of it is very deflationary for expectations and prices.