Westpac with a good note. Albo has slain wage growth with quantitative peopling.

The cost-of-living crisis has brought intense focus on inflation measures over the last two years, including the intricate detail on goods and services and on some more obscure measures that do not often get coverage. One that has been given particular emphasis in the Australian context over the last month is ‘unit labour costs’ – the RBA Governor even indicating that the evolution of this cost measure sits at the centre of ‘next phase’ of getting inflation back to the 2-3% target range. ‘Unit labour costs’ are basically a measure of the productivityadjusted cost of labour, or to put it more simply, what it costs to produce a unit of output as measured by the National Accounts.

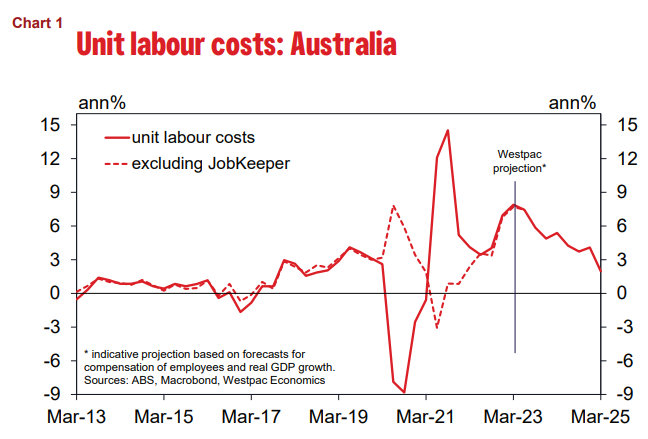

As such, changes capture the combined effect of two elements: 1) wage inflation; and 2) changes in productivity. Official measures are provided with the quarterly National Accounts, with the June quarter update due on September 6. For policy, the central concern is the high starting point with unit wage cost growth running at 7.9% over the year to March. This is largely due to a poor productivity performance with GDP growth barely keeping pace with the rise in hours worked. If that poor performance were to continue, then inflation would be unlikely to below 3% even if wages growth remained benign. However, a couple of points are worth noting. Firstly, derived measures like productivity and unit labour costs can bounce around a lot, are subject to meaningful revisions and have been particularly volatile during the COVID period, due both to lock-downs and the scale of policy measures. The latter had a particularly significant impact on unit labour costs due to JobKeeper support, which amounted to a large subsidy for labour costs in 2020 that rolled off in 2021 (see Chart 1).

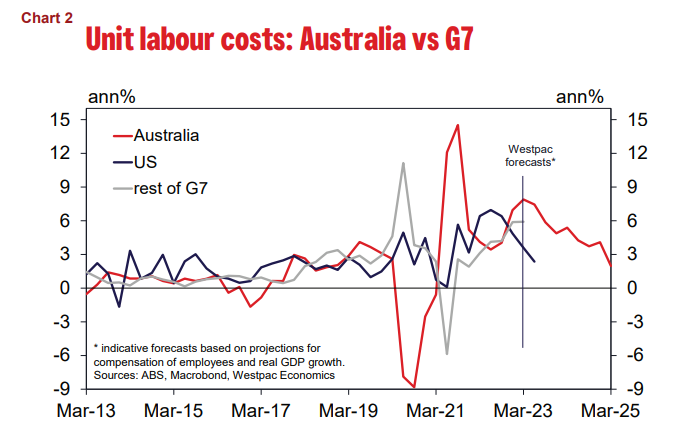

More generally, like the inflation surge, the robust growth in unit labour costs over the last year also looks to be part of a global phenomenon. Across the G7 developed economies we typically benchmark Australia to, unit labour costs rose 6.7%yr in 2022, hitting multi-decade highs in most countries (excluding the COVID period). Moreover, to the extent that there is a common driver, there are also signs that the surge is temporary. The US, which has led the way through the post-pandemic inflation story to date, has seen a material slowing in unit labour cost growth which has tracked back to 2.4%yr as at June (see Chart 2).

Australia will probably see something similar. While unit labour costs are not something we formally forecast, we can back out an implied projection from our views on wage incomes and forecasts of GDP growth. This indicative path has unit labour cost growth gradually tracking lower over the next two years, to just over 4%yr in 2024, as wages growth slows to around 3.2%yr after peaking at 3.9%yr in September 2023 and moderating to 3.8%yr at end-2023. That should be enough to allay the RBA’s concerns (see Charts 1, 2 or 3).

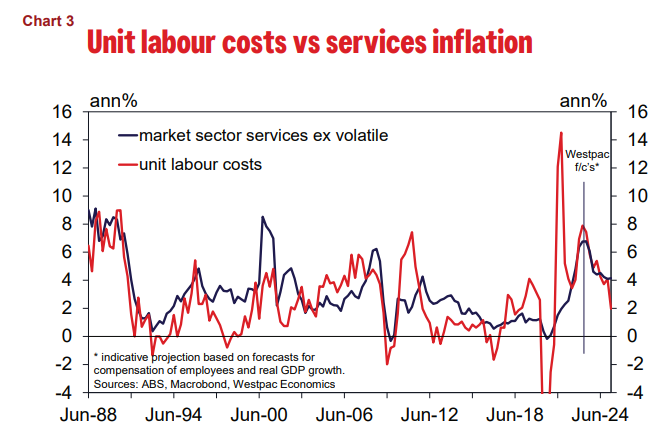

While some slowing is highly likely, in practice the path is unlikely to be a simple straight line and judging prospects will be difficult. It will require corroborating evidence, especially from the detailed inflation updates. Unit labour costs are essentially the ‘cost-base’ for domestic production and have particularly strong links to price-setting in sectors that face little or no international competition; the ‘market services’ sector is a particular standout here. Hence, market services components of inflation will be watched very closely for signs of lingering price pressure.

Westpac forecasts have market services inflation (excluding the volatile components, so more of a core measure) easing back from a peak of 6.8%yr at June 2023 to 4.6%yr by end 2023 and then down to 4.1%yr by end 2024 (see Chart 3). For interest rates, these concerns will tend to play out as a constraint on any policy easing rather than a cause for additional tightening. If the slowing in unit labour cost growth is too gradual the Bank’s fear will be that inflation may take longer to get back below 3% or even get stuck above target – moving to less restrictive policy settings in that situation would be untenable.

This is not to downplay the RBA’s wider concern. As Treasury’s latest Intergenerational Report highlights, productivity growth sits at the heart of Australia’s medium to longer term prospects. Accumulated over decades, a few percentage points difference in average growth make an enormous difference. Australia’s poor productivity performance over the last year is unsettling but may at least be partly cyclical. The poor performance over the last five years is much more troubling (see Chart 4). With major challenges ahead, particularly from population ageing, adapting to climate change and transitioning away from carbon based energy, it is imperative that Australia finds a way back to an improved productivity performance. Policy-wise, that’s a task for governments rather than the RBA.