Last week, the Liberal deputy leader, Susan Ley, appeared on Sky News where she demonstrated that she is just as useless on housing policy as Labor.

Instead of demanding the Albanese Government reduce net overseas migration to sensible and sustainable levels, she instead said that “we have to build our way out of” the housing crisis:

“The main thing that needs to happen is that supply needs to be pushed from the state level”, Ley said.

“What makes sense is to unblock supply and for the state governments to actually be pushed into doing this in a way that makes a difference on the ground”.

“So Supply is the area to be fixed. Supply is always the answer. It’s the number one thing”.

Ley’s sentiments were echoed by Teal Independent for the posh electorate of Wentworth, Allegra Spender.

Spender backed the Albanese Government’s record immigration, and instead called for more supply:

“A couple of months ago we had the lowest housing approval for a number of years. And this is a time where increasing supplies absolutely critical”, Spender said.

“So I’m calling on the government to use, you know, the money in the Federal Budget to really incentivise the states to make fundamental changes to planning and zoning laws”.

Both essentially argued that increasing supply is the only solution to the nation’s housing crisis, and it requires action from the states.

Meanwhile, reality continues to smack the supply-siders in the face.

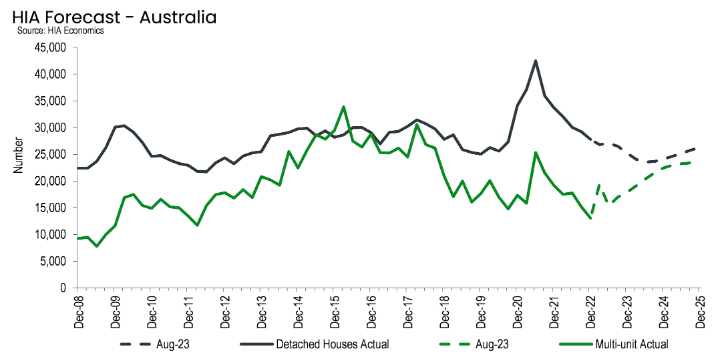

On Tuesday, the Housing Industry Association (HIA) released its forecast for dwelling starts:

Detached houses:

After reaching a high of 149,300 detached starts in 2021, new detached house starts are projected to dip to 95,370 in 2024, the lowest amount since 2012.

From a low point in mid-2024, detached starts are predicted to rise gradually, supported by a strong economy and population expansion, to 110,820 by 2027.

Multi-units:

There were only 63,510 multi-unit starts in 2022, a decade low, with only a 9.7% increase to 69,680 predicted in 2023.

Stronger improvements of 19.8%, 11.6%, and 0.9% are projected to bring the annual total back to 94,030 by 2026, before a 2.8% decline to 91,360 in 2027.

“Even if the RBA were to cut rates today, detached home building activity is set to slow to its lowest levels in more than a decade”, warned HIA’s Chief Economist, Tim Reardon.

“The number of new homes commencing construction peaked in June 2021 and is set to continue to decline for another year under the weight of rising interest rates and land costs”.

“Recent projections of demand for housing among state governments have failed to appreciate the growth in population or the number of homes required for each new resident”.

“Despite this need to increase housing stock, the number of new homes commencing construction is set to stagnate”.

“Even a decision to cut the cash rate today would not produce a recovery in house commencements until the second half of 2024″, Reardon warned.

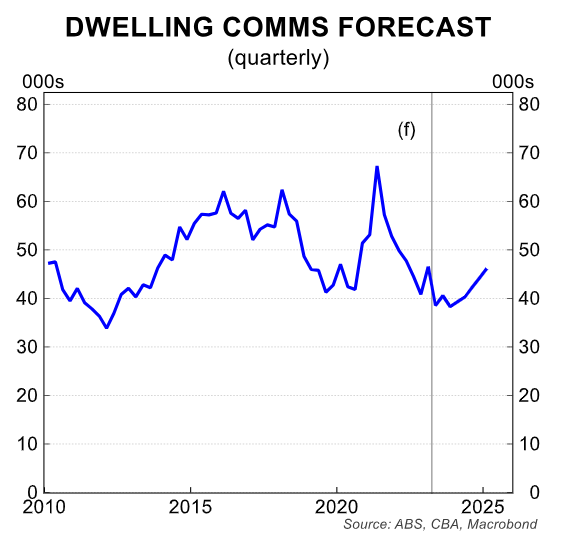

CBA’s economics team has likewise forecast a sharp fall in housing construction.

There were 183,000 dwelling commencements in 2022, and CBA forecast this number to fall to 164,000 in 2023 before seeing a modest rise to 166,000 in 2024:

Let’s get real: the federal government’s reckless mass immigration policy is the primary cause of Australia’s housing shortfall.

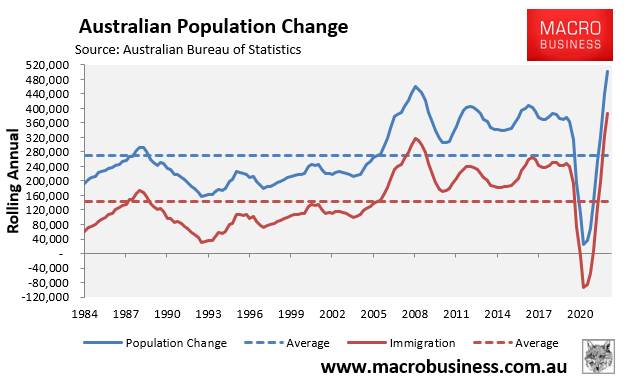

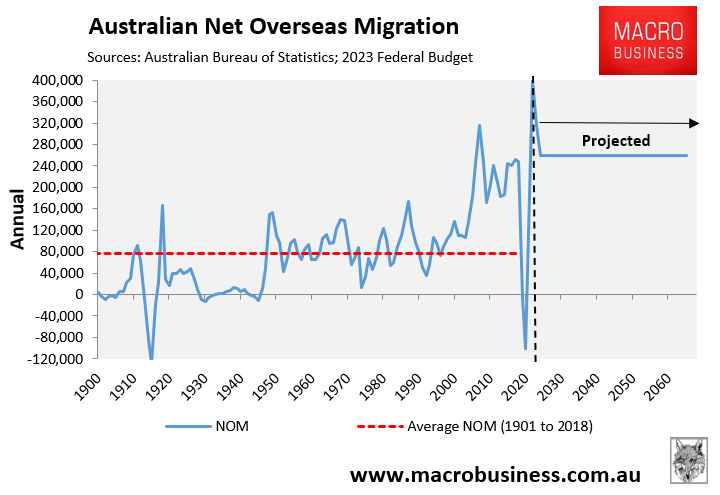

From a record net overseas migration (NOM) of 387,000, Australia’s population grew by an astounding 500,000 persons in the 2022 calendar year:

Put another way, Australia’s population increased by 1,369 people per day last calendar year from record NOM of 1,060 people a day.

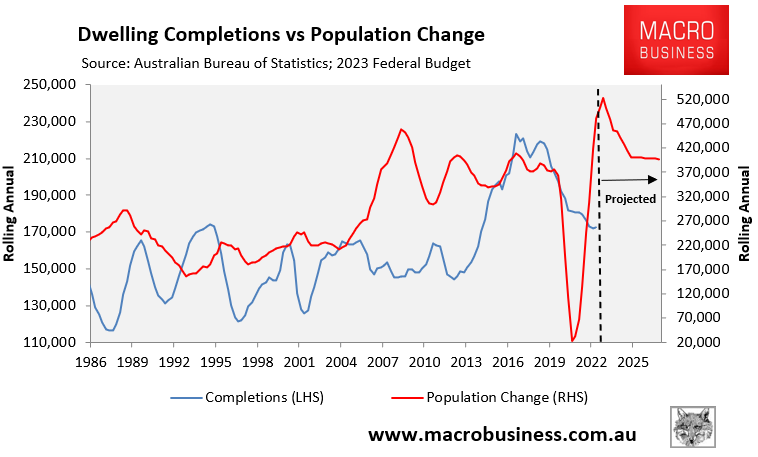

The current population density per home in Australia is approximately 2.5.

Dividing this daily population/NOM increase by this figure gives an estimate of how many homes need to be added to Australia’s housing stock to keep up with the country’s population growth.

To meet the increasing population, Australia required 548 extra homes every day last year, with 424 of these new homes required only for new migrants.

Instead, Australia added 154,400 homes to its housing stock in 2022, a rate of 423 units per day.

According to the May federal budget, Australia’s population would expand by 2.18 million over the five years to 2026-27, with NOM accounting for 1.5 million of this increase.

That is the equivalent of adding a Perth-sized population in five years, with an Adelaide-sized population coming entirely from NOM.

This indicates that during the five years to 2026-27, Australia will add 1,194 people every day, with NOM accounting for 822 of this increase.

Using the 2.5 people per home ratio, this suggests Australia would need to supply 478 new homes per day, with 329 of these homes dedicated solely to new migrants.

Australia will also need to build more than this number to account for losses in the housing stock via demolitions.

Given that actual building rates have already fallen sharply as a result of widespread builder insolvency and increasing material and financing costs, and are projected to continue doing so, there is no hope of fulfilling these lofty housing supply targets.

Therefore, Australia’s housing shortages will worsen as a direct result of the Albanese Government’s reckless mass immigration program, driving up rents and pushing thousands of Australians into homelessness.

The only solution to Australia’s housing shortage is to reduce net overseas migration to levels consistent with the country’s ability to deliver housing, infrastructure, and services.

Net overseas migration should be reduced to historic levels of roughly 100,000 persons per year.