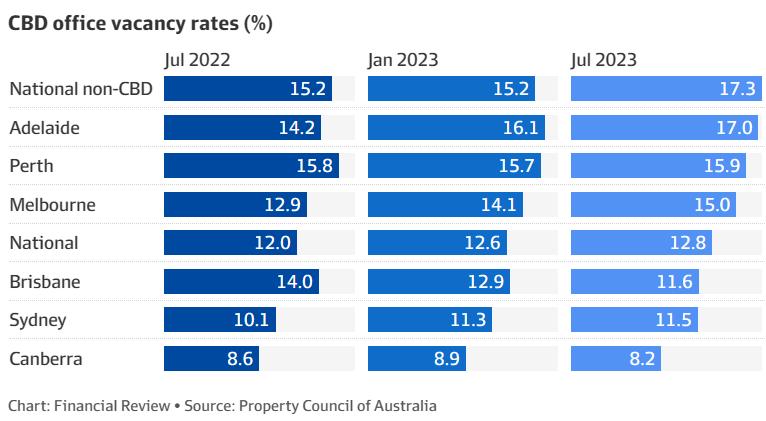

Earlier this month, the Property Council of Australia (PCA) released data on CBD office vacancy rates, which have lifted to their highest level since 1996 (12.8%) across the capital cities:

The Sydney CBD office vacancy rate has climbed by 20 basis points to 11.5%, owing to weaker demand for office space. Melbourne’s vacancy rate increased by 90 basis points to 15%.

Several firms and government agencies relocated or reduced their office requirements during this time period.

PCA CEO Mike Zorbas said demand for office space has declined due to corporations downsizing in anticipation of a global recession.

However, negative demand was not the sole reason for rising vacancy rates in Sydney and Melbourne, according to the PCA, which also cited above-average office supply growth since 2020.

“The very big peak in supply additions in 2021 and 2022 – well and truly eclipsing the average – explains a lot of where we are now”, Zorbas said.

The PCA expects commercial vacancy rates in Sydney and Melbourne would rise further in the second half of 2023 as more leases expire.

This viewpoint is shared by tenant advocate Steve Urwin of Kernel Property, who believes Melbourne’s CBD has become overbuilt and that vacancy rates will worsen.

“It’s bad now but the anticipated peak vacancy is not here yet. It’s atrocious at the moment, and it’s getting worse”, Urwin said.

“Last time we had this in Melbourne was in the early ’90s when the city was overbuilt. It really did take a couple of decades for the city to properly recover and now they’re building more and more stuff again”.

Urwin added that the genuine vacancy rate in Australia could be considerably higher than the PCA’s assessment because “shadow vacancies” were not taken into account.

These are empty office spaces that are still being rented despite the fact that they are scarcely inhabited owing to shifting work patterns.

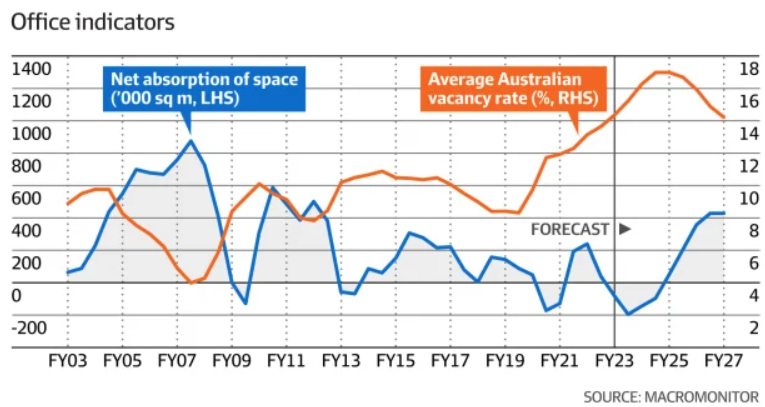

Construction research firm Macromonitor reported on Thursday that national office vacancy rates could rise another 4.2% to 17% by June 2025, because the impacts of weakening demand and rising supply is yet to be fully felt by the sector:

Office commencements are set to soar by 44% to $10 billion in the 2024 calendar year as office demand continues to soften.

“New supply will be high in the near term, and we expect office demand to remain weak due to slower economic growth and the effects of work-from-home steadily flowing through to office occupancy”, Macromonitor economist Emily Bray said.

“The result will be high vacancy rates across the country getting even higher, and a decline in new office building starts”.

Macromonitor forecasts that over the next three years, Sydney landlords are likely to withdraw between 160,000 and 230,000 square metres of office space every year, while Melbourne landlords are expected to withdraw around 120,000 square metres per year.

“They’re not going to get the return they’re looking for in the office, so it looks like many will withdraw and convert them into residential buildings, where they will get more returns”, Bray said.

“If space is not withdrawn at the level we expect, vacancy rates could be considerably worse.”

Roy Morgan’s Taking The Pulse of the Nation report showed that remote work has become entrenched in Australia:

“Almost all workers (94% in June 2023) would like to work at least part of their work hours at home, and 64% would like a hybrid arrangement where they work both at home and the office”.

“Employers largely agree, with 60% of workers reporting their employers would permit hybrid work. This increased from 49% of employers permitting hybrid work in April 2021”.

This poses a dilemma for commercial real estate investors and financiers: If people never again work in offices like they did before the pandemic, how secure are their fortunes?

Falling office demand and record supply can only mean one thing: a commercial property bust on the scale of the early 1990s recession.