Yarra Capital chief economist, Tim Toohey, has published terrific analysis arguing that the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) sudden focus on labour productivity and unit labour costs risks a “policy induced doom loop”.

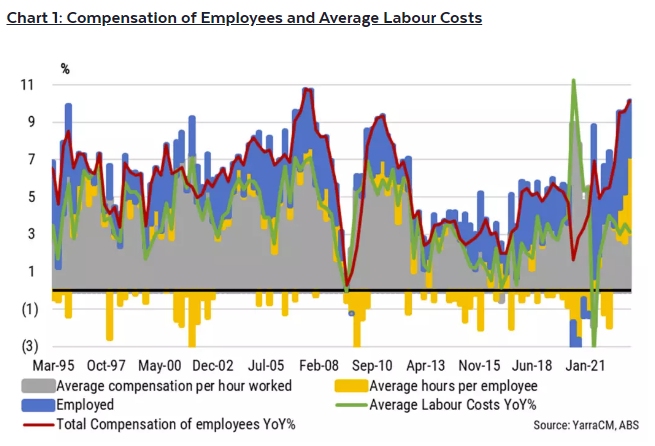

Toohey contends that the strong growth in compensation of employees and average labour costs (see below chart) has primarily been driven by two factors:

- The strong growth in the number of employed people, driven lately by record net overseas migration.

- An increase in the number of hours worked per worker.

“Putting this all together, the reason unit labour costs (ULCs) are high is not because people are getting paid excessively for each unit of work done”, Toohey writes.

“It is because people are working a lot more hours, in part due to there being more people in the country and in part due to increased effort”.

Toohey then explains that labour productivity has dived primarily because the RBA’s aggressive interest rate hikes have slowed growth in GDP.

Therefore, Australia will face a chicken-and-egg situation if the RBA continues to hike rates because of rising unit labour costs, which are being driven in part by falling labour productivity (via slower GDP) from the RBA’s own tightening:

“When economic growth slows, by definition, productivity declines cyclically. i.e. you are selling fewer less widgets but with the same inputs of capital and labour”.

“Economic output growth barely grew in March and has slowed sharply to just 2.3% yoy”.

“On a per capita basis the economy has shrunk over the past six months and the data we have at hand for the June quarter suggests that worse growth outcomes lie ahead in the remainder of the year”.

“This slowdown has come about directly in response to the RBA’s tightening cycle and the Government’s attempt to get out of the RBA’s way and curtail its spending”.

“If we are raising rates because of a short-term cyclical fall in productivity, then we are caught in a policy induced doom loop”.

“The RBA seems to be putting large weight in the recent decline in productivity”.

The above is also an acknowledgment of the ‘burnout economics’ that is currently taking place in Australia.

The Albanese Government has its foot planted firmly on the accelerator by running a record immigration program, which is adding workers to the economy at an unprecedented pace and is boosting aggregate compensation of employees.

At the same time, the RBA has its foot jammed on the brake via the steepest interest rate hikes in Australia’s history.

This ‘burnout economy’ set up necessarily means that labour productivity will fall since more workers are being added to a slowing economy, in turn driving up unit labour costs.

The RBA should ignore short-term cyclical swings in labour productivity when setting interest rates.

Otherwise, it will hike too far and drive the economy harder into an unnecessary recession.