The excellent Gerard Minack with the note.

Recession risks rise as Australian income collapses

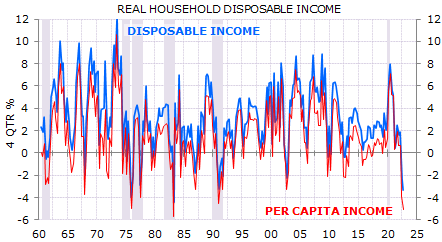

Australian household disposable income is now falling at the fastest rate ever, outside of recessions.

While households have a buffer of unspent pandemic benefits, debt service payments are rising as fixed-rate mortgages expire, and renters are being squeezed in a tight property market.

All this points to a significant slowdown in consumer spending in the second half. If the RBA were to tighten further – a 50:50 bet in my view – a recession would become my base case.

Real household disposable income is now falling at the fastest pace in 40 years – and at a rate never seen outside of a recession (Exhibit 1). Per capita income growth is even weaker.

Part of the income decline was due to the acceleration in inflation.

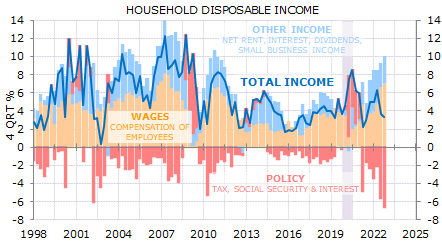

All else equal, pressure on real incomes will moderate as inflation falls. But policy measures are also taking a big bite out of income, subtracting 7 percentage points from nominal income growth last year (Exhibit 2).

Policy will remain a headwind for incomes for some time.

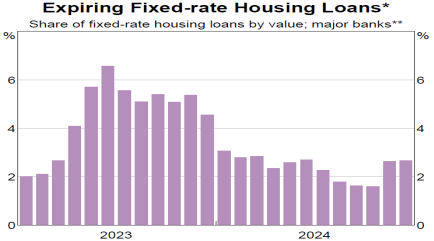

Effective income tax rates are rising due to bracket creep, while a large share of outstanding fixed-rate mortgages will expire in the second half of this year, lifting debt service (Exhibit 3).

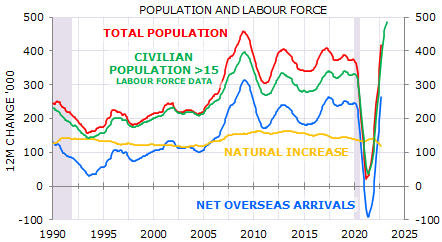

Meanwhile labour supply is rising as migration numbers rebound (Exhibit 4).

Fast labour supply growth is mitigating the RBA’s principal concern: that wage growth will accelerate to a level incompatible with its inflation target.

Evidence that wage growth is running too hot is everywhere except in the hard data.

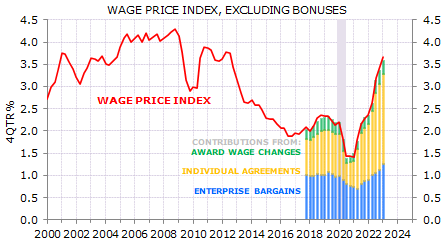

The Wage Price Index is moving sideways. The headline index increased by 3.4% at an annual pace over the two quarters to March, down from 3.9% over the two quarters to September 2022.

Wage growth remains below the 4% threshold that is acceptable to the RBA.

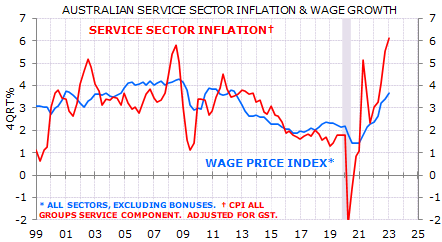

History suggests that service sector inflation will ultimately settle around the growth rate in wages (Exhibit 5).

There is likely to be an inflation-based uplift to the minimum award wage later this year. However, award wage changes are not a big contributor to changes in aggregate wage rates (Exhibit 6).

There is likely to be an acceleration in public sector pay, particularly in the health and aged care sectors.

However, these are sectors with a high share of public funding – which will cover much of the increased labour costs – so there is not a direct link between wages and prices in the CPI basket.

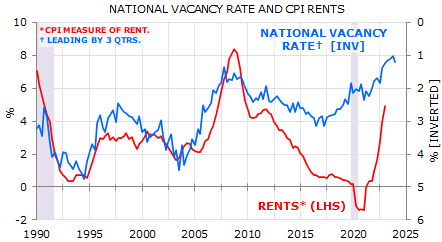

The breakneck pace of population growth is a mixed blessing. Fast labour supply growth will damp wage growth, but it is also contributing to an exceptionally tight housing market, which in turn points to rising rental inflation (Exhibit 7).

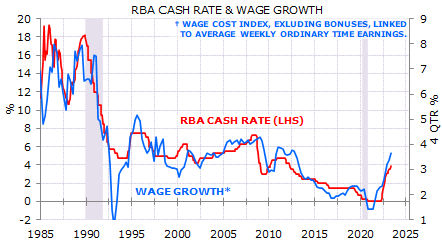

It seems clear that headline inflation has peaked. It’s not clear that wage growth has peaked, which is crucial to the rate outlook given the long-standing link between wages and RBA policy (Exhibit 8).

However, wages are a lagging indicator.

With household income falling, consumer spending is likely to weaken through the second half of the year.

The prospect of slower consumer spending and rising labour supply points to a significant easing of labour market conditions.

I do not think that further policy tightening is required.

However, it’s probably a 50:50 chance that the RBA continue to tighten policy.

With policy already restrictive, even just 1 or 2 rate increases would risk tipping Australia into recession later this year.