Last week, MB lambasted the Grattan Institute’s Tony Wood – a former Origin Energy Executive (Origin are also a key financial sponsor of Grattan), and somebody who argued vehemently against east coast domestic gas reservation – for claiming that Australian households should abandon gas appliances to achieve ‘net zero’.

“Residential gas use is tiny and most of it is heating. Stove emissions are so marginal to the decarbonisation goal that Grattan might as well campaign against farting”, MB’s David-Llewellyn-Smith wrote.

“Why is not tackling the big issues round gas like smashing the east coast gas cartel so that the energy transition can proceed without ruining our political economy every five minutes?”

He noted as well that Grattan is sponsored by gas export cartelier Origin Energy, and Tony Wood, who composed the report, is a form executive at the same.

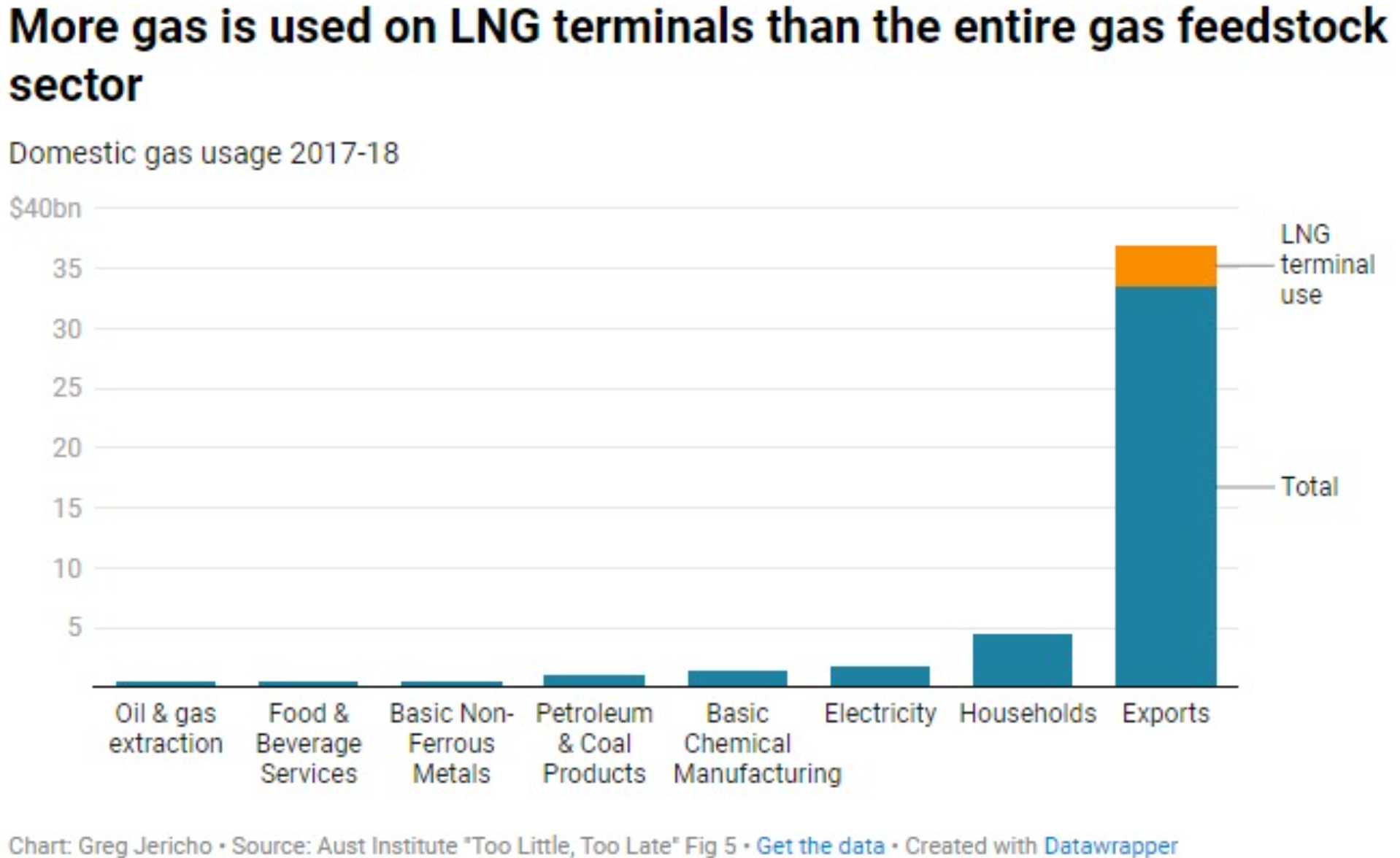

Australian household gas use pales into insignificance against the amount of gas that we export.

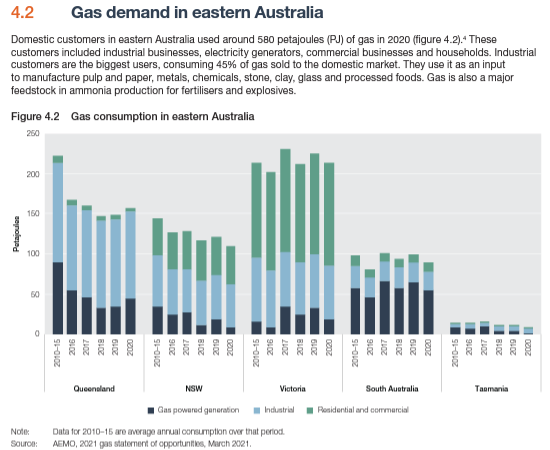

Heck, the gas cartel burns far more gas converting it to LNG (orange bar below) than we use on stoves. So why isn’t Grattan critiquing that?

Now Aidan Morrison has taken Grattan apart at Fresh Economic Thinking.

Grattan’s gas gimmick – To jump on the bandwagon they must ignore their own analysis

It saddens me to say this, but it’s clear now that the Grattan Institute has caved.

They’re now ignoring and obfuscating their own research in order to bandwagon with fashionable vanity projects that have trivial environmental value and significant economic costs.

In this case, the bandwagon is converting residential household gas appliances for heating and cooking to electricity.

Their new paper, entitled Getting off gas, opens by asserting that getting off gas matters because of greenhouse gas emissions.

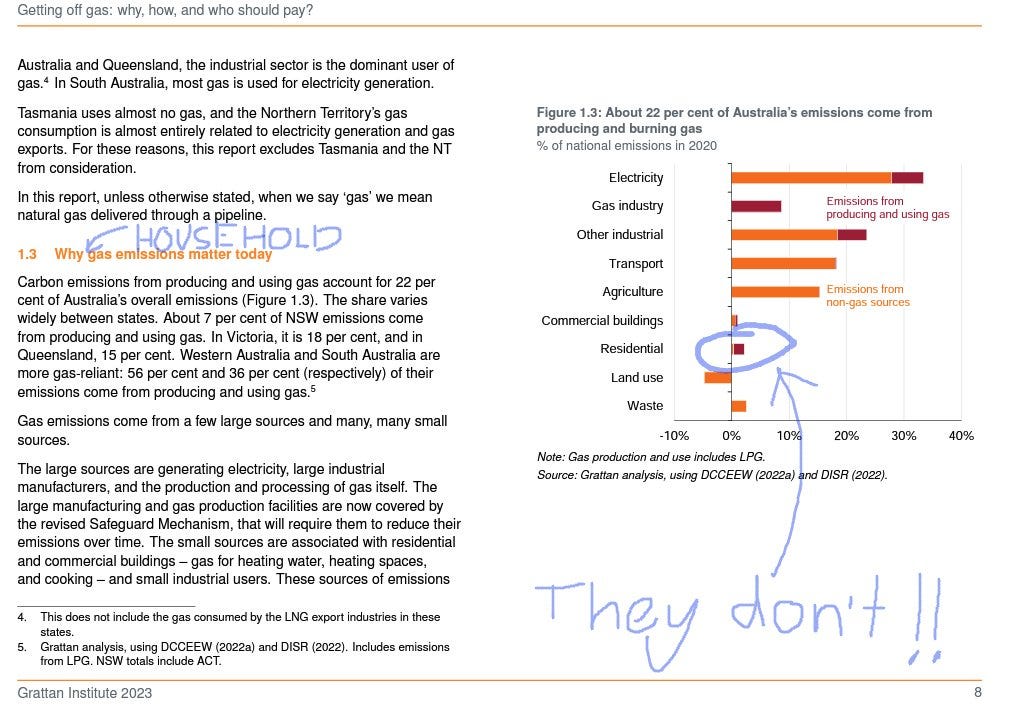

The big scary number they promote about the share of Australian emissions from gas is 22%.

But their own graph shows that households are a tiny fraction of that 22%. They avoid quoting the actual proportion of total emissions from household gas (which is shameful). It looks to be only around 2% to me.

They basically skip the serious gas emissions from electricity production and heavy industry (there’s a brief mention in Section 8 of the report), and proceed to dedicate Sections 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, to the trivial household emissions.

Why?

Because the vibes say it’s an easier place to start.

Then comes the bombshell that collapses the entire premise of the paper.

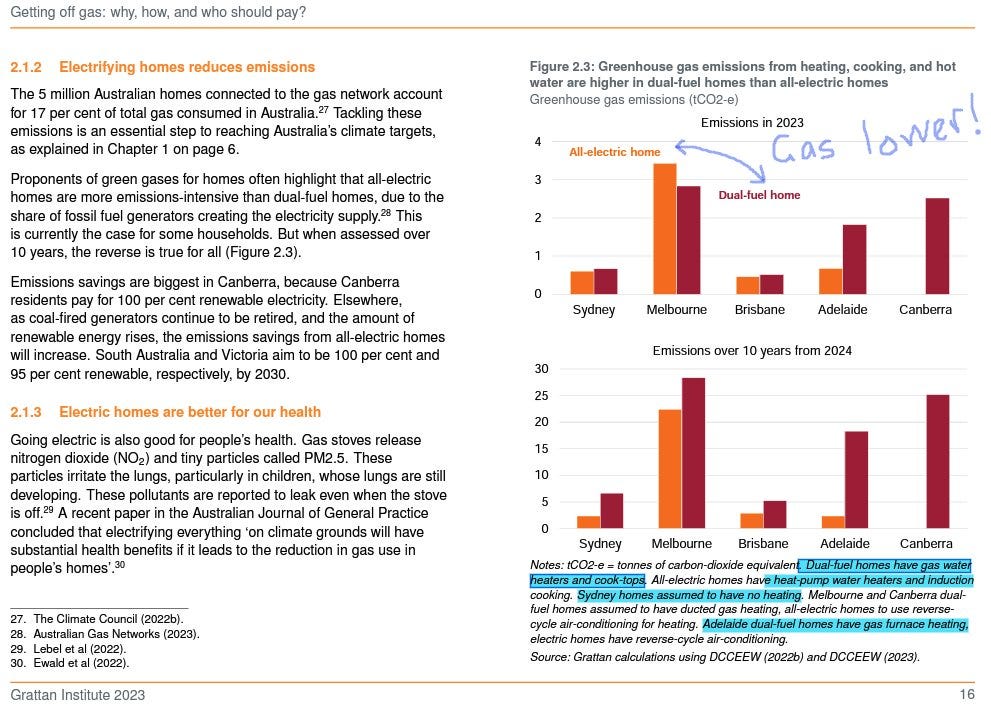

In Melbourne, which dominates household gas use, switching off gas increases emissions!

Only a 10-year projection based on a slew of assumptions just slightly tilts the switch from gas to electric in Melbourne to be favourable in terms of emissions.

This matters because Melbourne dominates household gas consumption. Adelaide, Canberra and Brisbane don’t really matter at all.

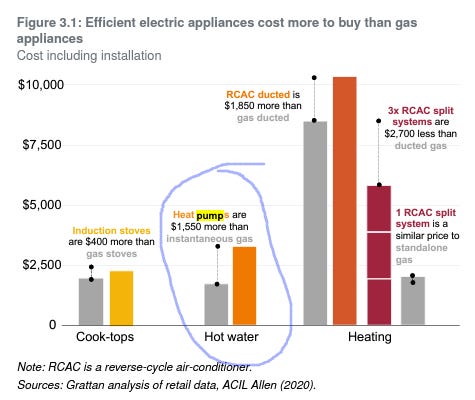

One of their key assumptions is that all-electric homes have heat-pump hot-water systems, which use around a third of the energy of conventional electric systems.

Weakening this assumption alone is enough to overturn the benefit that Grattan ascribes to a switch.

Currently, these systems are quite rare. There’s good reason to think they’ll remain so – they cost double (according to Grattan) what an instantaneous gas system costs.

So if everything goes perfectly with Victoria’s energy transition (it won’t), and we assume electric homes have super-expensive, super-efficient water heaters (they don’t) then in ten years an electric switch might reduce household emissions—a tiny little bit.

Grattan doesn’t name the number of this reduction, (another shameful omission) but from the published graphs I’d guess it is no more than 20% of emissions from current household gas use. (Which are ~2% of overall emissions.)

Nope.

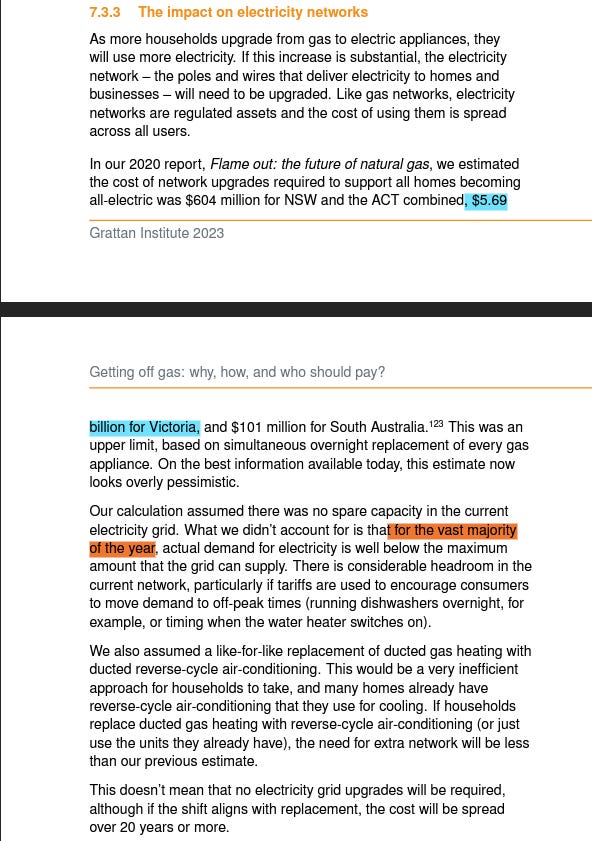

By Grattan’s own analysis, the grid upgrade in Victoria would cost $5.7 billion.

They shamelessly try to walk their own analysis back at this point. In doing so, they ignore the engineering costs that demand peaks impose, claiming that some headroom ‘for the vast majority of the year’ has value (it doesn’t).

Furthermore, this price doesn’t include generators, which are meant to be increasingly intermittent and worse in winter. Squaring that circle will be expensive at best.

It’s much more likely that getting off gas would make it harder to get off coal, which is the true source of the bulk of Australian emissions (and reliable electricity on winter nights).

The entirety of Section 7 is basically devoted to discussing how extremely difficult it will be to finish what was so gladly proclaimed in Section 2 as the easiest place to start. And yet somehow, they avoid actually revisiting the conclusion that the endeavour should, in fact, be started.

- Household gas emissions are trivially small (~2% of Australian emissions).

- And they mostly come from Melbourne, where a switch to electricity would increase emissions

- Unless we spend roughly $6 billion on grid upgrades, plus everything else required to make renewables reliable in winter, plus subsidies or incentives to switch appliances.

- And even then, after ten years of unrealistic assumptions, it would be only be a small (~20%) reduction of the ~2% of the emissions that household gas comprises. That’s less than 0.5%.

‘Getting off gas’ is an expensive vanity project by any measure.