The AFR View released an editorial this week asserting that “Australia’s housing affordability crisis is due to the supply side, stupid.”

That, The AFR claimed, is the lesson policymakers must learn, according to research from former Reserve Bank economist Tony Richards.

The crux of Richards’ argument was that, in the 20 years leading up to 2021, the rate of home building relative to population growth dropped dramatically.

As a result, 1.3 million fewer residences were built than would have been the case if the rate of dwelling construction had been consistent with the previous 20 years to 2001.

The inference from Richards’ research was that Australia has gotten worse at building homes, leaving the country desperately short of housing, culminating in the current affordability catastrophe.

The media, the property lobby, and policymakers constantly spruik this ‘lack of supply’ mantra. However, it is fundamentally incorrect.

Australia is a world leader in home construction

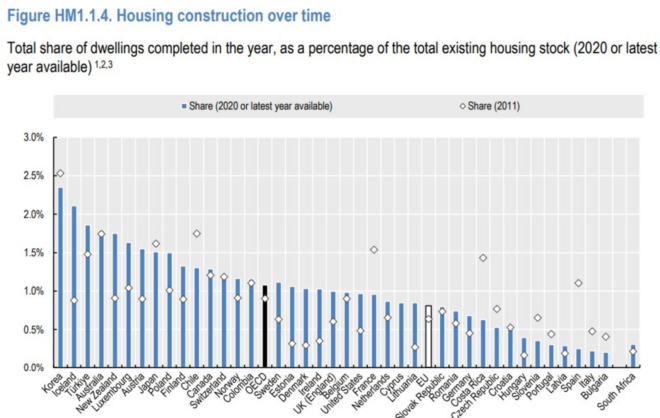

The OECD’s Affordable Housing Database shows that Australia has built significantly more dwellings per capita than most other OECD countries:

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database

In 2020, Australia ranked fourth in the OECD for home building.

Australia’s residential construction rate also remained constant from 2011.

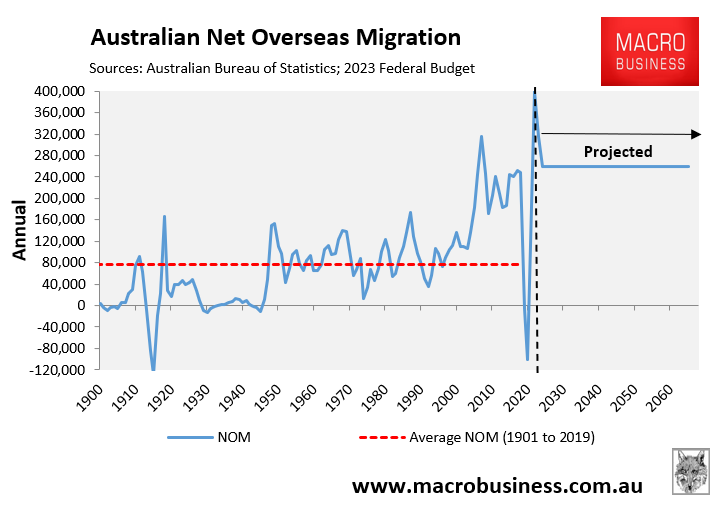

The primary issue is not Australia’s inability to build houses, but rather the fact that Australia has one of the world’s largest immigration programs, ensuring that housing demand always exceeds supply.

In the 20 years leading up to 2001, Australia’s net overseas migration (NOM) averaged 95,000 persons per year, while population growth averaged 217,000.

Australia’s NOM averaged 182,000 in the 20 years to 2021, and population growth averaged 320,000 people a year. And this time span encompasses the pandemic’s negative NOM.

If the May Federal Budget’s aggressive immigration projections come true, the housing supply problem will only worsen.

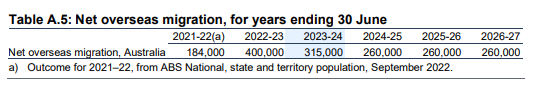

According to the Budget, NOM will hit a record high 400,000 in 2022-23, before decreasing to 315,000 in 2023-24.

It will subsequently fall to a historically high 260,000, where it will remain thereafter:

Source: 2023 federal budget

As a result, the Federal Budget anticipates a record 1.5 million net overseas migrants arriving in Australia over the next five years, more than the population of Adelaide.

In turn, Australia’s population is expected to grow by a record 2.18 million people during the same five-year period, which is equivalent to adding five Canberras or one Perth to the country’s existing population.

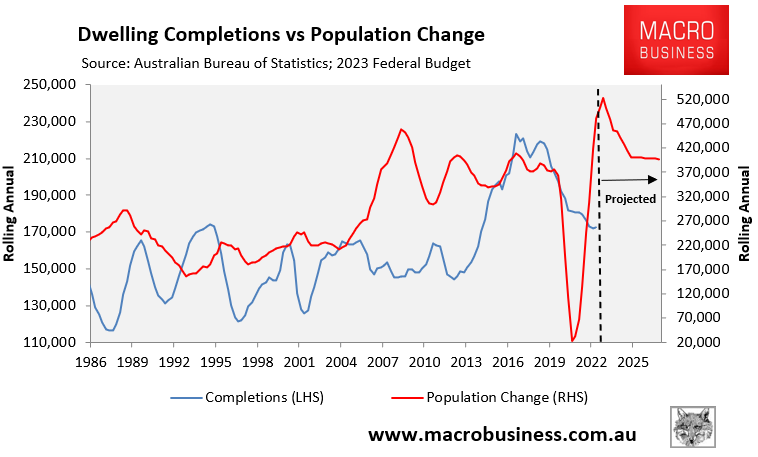

The following chart, which compares dwelling completions to actual and expected population growth as indicated in the Federal Budget, captures the immensity of Australia’s housing supply crisis:

As can be seen, Australia’s rate of home construction increased dramatically in the 2010s.

However, this construction boom was unable to keep up with the significant surge in immigration-driven population growth that began in the mid-2000s and is projected to reach new heights in the future.

The housing shortage in Australia will worsen

Even under ideal housing conditions, building homes for such a tremendous increase in population is an impossible task.

It’s even worse when the entire housing construction industry is on the verge of collapse due to widespread insolvency and soaring material and financing (interest rate) costs.

According to ASIC data as of 14 May, 1872 home builders have declared bankruptcy in 2022-23, the highest number on record.

Among the above-mentioned insolvencies are industry giants such as Porter Davis Homes, which went into administration in March with over 1500 homes partially completed, as well as a bevy of smaller builders.

It is anticipated that builders responsible for approximately 5200 homes worth a total of $2.2 billion have gone bankrupt since 2021.

As a result, there are fewer builders left to meet the country’s housing needs in the face of unrelenting immigration demand.

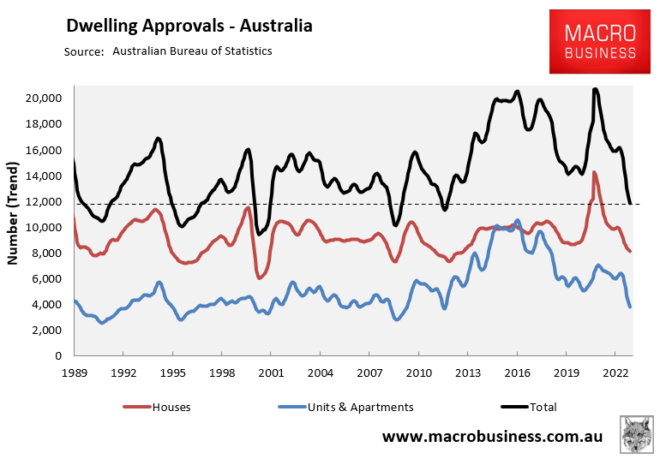

The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ dwelling approvals numbers April were a complete disaster, with overall approvals falling to a 13-year low:

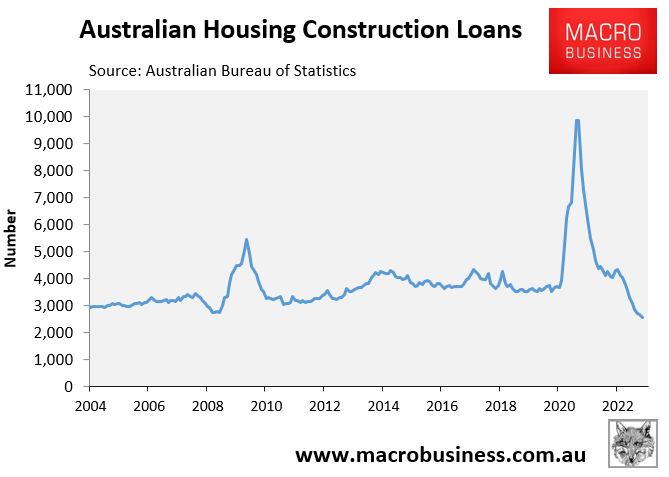

The number of loans taken out to build new homes also crashed to its lowest level on record, down 74% from its January 2021 peak:

To add insult to injury, Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy stated last week in Senate Estimates that the decline in dwelling approvals is expected to last until 2025, with investment in new dwellings likely to fall by 2.5% this year, 3.5% in 2023-24, and 1.5% in 2024-25.

Blind Freddy can see that growing Australia’s population by 400,000 to 500,000 people per year while building fewer homes means the country’s housing situation will worsen, resulting in higher rents and increased homelessness.

It’s the immigration, stupid!

Australia’s housing shortage is a direct outcome of two decades of excessive immigration, which is officially projected to reach record highs in coming years.

Australia will never build enough homes as long as its population continues to grow rapidly as a result of extreme levels of immigration.

We did not construct enough homes during the 15 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration preceding the pandemic. And we surely won’t under the Federal Budget’s planned record immigration influx.

If the Albanese Government actually cared about ending the nation’s housing shortage, it would operate an immigration program that was significantly lower than the nation’s ability to supply new homes, not the other way around.

It is past time to stop blaming a ‘lack of supply’ and face the immigration elephant head on.