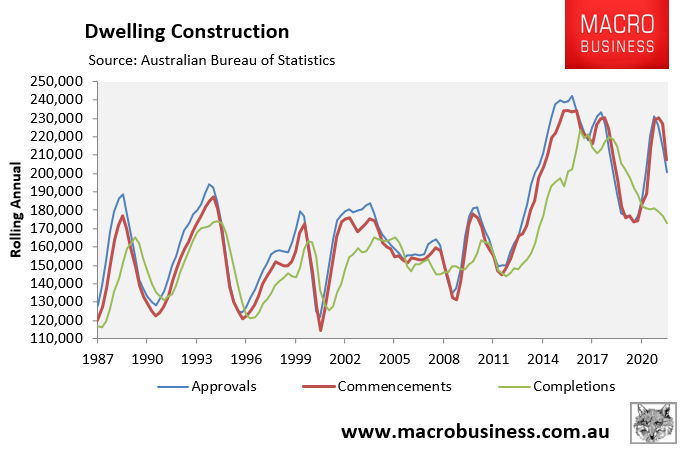

Australia’s quarterly dwelling construction data shows that there is a gaping gap between dwelling approvals and commencements and dwelling completions:

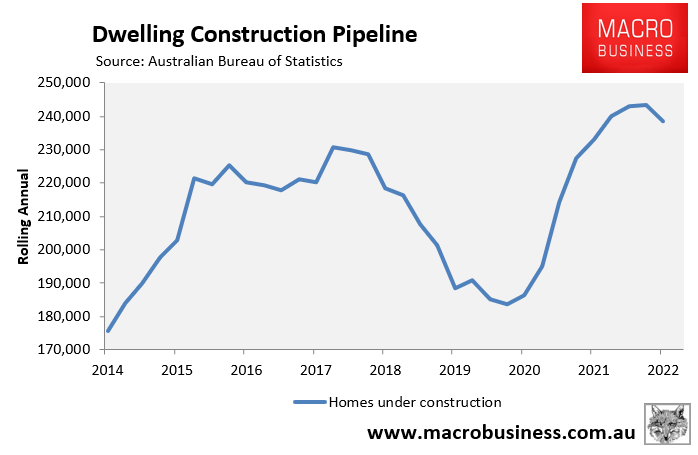

Because of this disconnect, Australia’s dwelling construction pipeline was sitting at a high 238,000 in the December quarter of 2022:

Last week, reports emerged that thousands of homes approved for construction have been put on hold amid soaring materials and financing (interest rate) costs.

Analysis from KPMG, estimated that 10,500 dwellings with planning approval in Victoria were yet to break ground by the end of March, up from 5,000 a year earlier.

In New South Wales, 16,400 dwellings with approval had failed to break ground by the end of March, up 2,600 in the last 12 months.

According to KPMG economist Terry Rawnsley, the rising cost of construction over the last three years – which has increased 29% in Sydney and 32% in Melbourne – is prompting developers to postpone certain projects.

“In the past we’ve never seen anything like this 30% increase over a 12 or 18 month period so we’re kind of in uncharted territory on the cost front’’.

“Two years ago a developer might have looked at building homes, which might have cost them $350,000 each to build but will now cost $500,000”.

“Two years ago, they thought they could sell them for $550,000, but maybe now it’ll only sell for $450,000 or $500,000, so they’ve paused that for the time being”, Rawnsley said

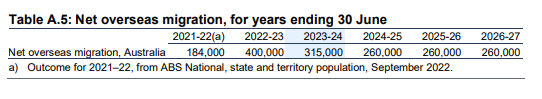

The cancellation of projects is obviously a disaster for Australia’s housing crisis, since it has arrived at the same time as the federal government projects a record 1.5 million net overseas migrants to land in Australia over the next five years:

Source: 2023 federal budget

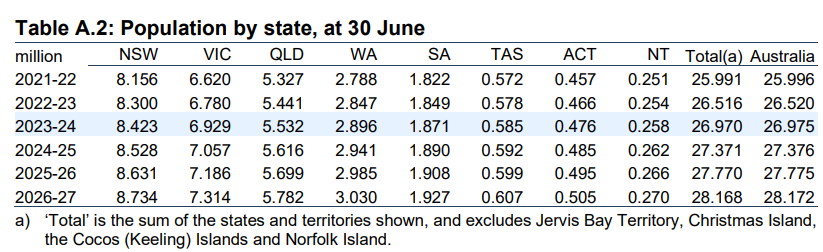

In turn, the federal budget projects that Australia’s population will swell by 2.18 million in just five years:

Source: 2023 federal budget

That’s the equivalent of adding five Canberra’s or one Perth to the country’s current population – in only five years!

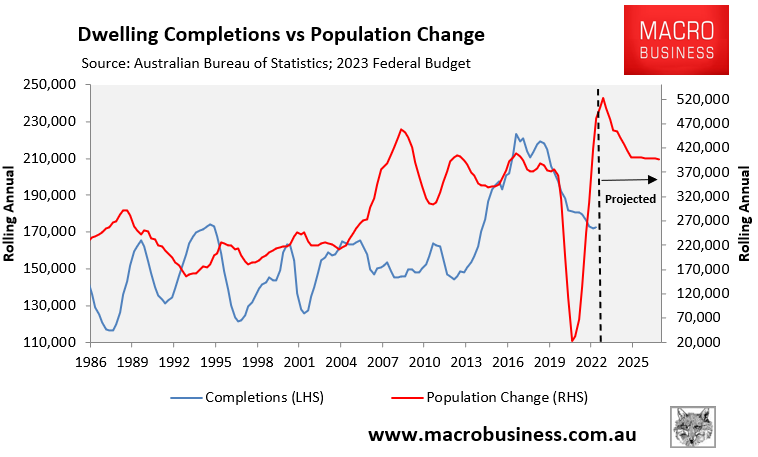

Australia did not build enough housing for the record numbers of migrants that landed in Australia in the 15 years leading up to the pandemic:

Therefore, providing housing for an extra 2.18 million people in five years will obviously be an insurmountable task, especially when the entire housing construction industry is suffering widespread insolvencies amid soaring materials prices and financing (interest rate) costs.

In turn, Australia’s housing (rental) crisis will continue to worsen, which will throw thousands of Australians into homelessness.

If the Albanese Government genuinely cared about ending the nation’s housing shortage, it would run an immigration program significantly lower than the growth of the overall dwelling stock, not the other way around.