Following the Great Pandemic of 2020, the global economy is entering a robust recovery. This new business cycle is not like those that have come after the previous two crises, the Global Financial Crisis and Tech Wreck. Those two crashes were led by the US and the recoveries led by China. This time around, the crisis was led by China and the recovery will be led by the US.

The difference is crucial to asset returns over the coming cycle. Aggregate global growth may appear to be the same at the headline level, but with the US the growth engine and China the caboose, the range and order of asset cars arrayed between them will be very different. So will be the returns for each.

Moreover, these cyclical forces will further be buffeted by epochal shifts in structural forces shaping the global economy which have, if anything, changed even more dramatically in the past few years.

What this means is that now is the time for investors to abandon Australia for global assets.

Structural forces

Liberalism

As John Maynard Keynes once observed: “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.” For much of the world over thirty years, this idea has been liberalism. The notion that economies grow faster and human progress is advanced more fully by unfettered economic freedom.

This is true. Free-thinking individuals motivated by higher living standards (and, yes, sometimes greed) do deliver immensely more of the innovation and productivity gains that are the secret sauce of capitalist advancement. The entire global economy is living, breathing proof of it.

That is not to say that liberalism comes in only one form. The post-colonial movement towards greater global freedoms has been under challenge now for a decade. Led, in particular, by China. The opening up of economic freedom in the Middle Kingdom since the 1990s has lifted a staggering number of people out of poverty worldwide. But it is now clear that it did so while its political freedoms remained repressed. In fact, for the past ten years, Chinese political freedoms have galloped backward into tyranny. The Communist Party of China has become little more than a gangster organisation dedicated fulsomely to power and the control of trillions in wealth.

At the same time, under pressure from the immense wealth of great winners of global liberalism, developed markets have seen a marked erosion in their public policy capability. Billionaires and corporations have warped the sensible centre of policymaking to also become a kind of duopolistic gangsterism in which two political parties compete over the same warped liberal outcomes. One could argue that this is not much better than Chinese illiberalism but that rather misses the point. Liberal societies retain all kinds of bulwarks for freedom in cultural expectations, the law, their parliamentary systems, as well as the right to protest for change. None of these exists in China, and the difference is stark for day-to-day living.

Even so, it is clear that the battle for supremacy between emerging market illiberalism and developed market liberalism was, until very recently, being won by the former. But that has suddenly changed.

COVID-19 is the major reason why. The China-spawned pandemic may never have reached foreign shores if had transpired within an open political system. That has aroused deep global suspicion of the Chinese politcal economy. At the same time, developed market liberalism has been forced to renovate the commons.

An outstanding example of change for the better is the USA. The election of the Trump administration in 2016 was a grenade thrown from behind the barricades mounted by those losing from gangster liberalism and globalisation. The shock of a right-wing populist regime capturing American working-class support radically altered the political calculus of the American left.

Combined with the pandemic, Trump was enough to shunt American politics back to the sensible centre, and away from gangster liberalism. This immeasurably strengthens liberalism’s core appeal. The forthcoming Biden administration infrastructure package is a triumph of policymaking that will both lift growth and living standards for years to come, especially in the forgotten working classes, as well as be self-funding via increased productive capacity. Gangster liberalism is in retreat.

At the same time, the appeals of the illiberal Chinese system are clearly waning. The CCP is disliked worldwide for its pandemic. Its diplomats have turned hostile. Moreover, and this is the key point, its economic development model is fast running out of steam. Productivity has collapsed and it is now China’s gangster liberalism that is the outstanding example of a political economy delivering inequitable and unsustainable debt-fueled growth.

The CCP understands this itself. Its solutions are in some ways appropriate and in others destructive. On the one hand, it is trying to restructure its economy away from the gangsterism that has driven over-investment in construction. On the other hand, the CCP is deliberately assaulting every developed market it can to generate a mindless nationalism at home, for it to manipulate.

The period ahead will likely see mixed successes on both counts. The economy will slow in trend terms as it slowly changes. The politics will get more aggressive as the first project is insufficient. Both come to a head in Taiwan.

Globalisation versus Cold War 2.0

The crowning achievement of liberalism for the past twenty-five years has been globalisation. The shifting of industrial production from developed markets to lower-cost jurisdictions has been enormous and ceaseless. This “hollowing out” resulted in chronic growth underperformance in developed markets as emerging markets boomed. In turn, inflation trended ever lower taking interest rates with it. In developed markets, capital flows adjusted by moving from hard economic producers to hard assets. From factories to houses, as it were. This has held up developed market growth via asset-price appreciation and over-consumption. As they sucked in imports, emerging markets enjoyed ceaseless export growth which pushed their capital to productive assets in the industrial economy.

This paradigm is now breaking owing to the global shifts in liberal ideology described above.

Led by the Anglosphere, the push back against emerging market illiberalism has already put the brakes on globalisation and the shift of production to emerging markets has slowed. This will continue in trend terms and will lead, sooner or later, into acute crises of sharp reversal. For instance, as the Taiwan conflict rises.

This will end in the structural Balkanisation of the global economy into two strategic blocks. One liberal empire governed from Washington. Another illiberal empire governed from Beijing.

The swing blocs in this scenario are Europe and Asia. Both will play the great powers off against the middle but, ultimately, will be forced to back the liberal forces. In Europe’s case, for its own intrinsic good and so that it can face down a resurgent Russia.

In Asia, China will aim to achieve strategic goals via economic coercion and by characterising the conflict as a racial struggle against a colonialist West. But Asia will seek a counter-balance in raw US power anyway. It has no love of China. Indeed, many states have deeper historical enmities with China than developed markets do.

As such, the American liberal empire will remain far larger in economic and military terms than the illiberal empire of China for as far as the eye can see.

Technology and climate change

If liberalism is the key idea behind human progress, and globalisation its economic expression, then technology is its material good. The industrial revolution, the rise of colonialism and its subsequent fall, and the rise of globalisation are all technological phenomena.

It is sometimes said that one reason behind the stagnation of developed markets over the past few decades is that they ran out of ideas for great technological advancement. There may be a grain of truth to this, though the internet begs to differ. Either way, that is not what lies ahead. Three great technological revolutions are coming fast that will disrupt everyday life for the better. As much as they did in the glory years post-WWII.

The first is driven by the necessity of climate change. In the next few decades, entire power grids will either evolve or collapse. The age of centralised energy is all but over. Ahead lies a radical evolution to the decentralised and local. What could give greater expression to freedom than that? Moreover, as it is completed, energy costs will continue to decline every year, sourced from sun and wind every day and stored in little boxes of chemicals.

The productivity and income gains implicit in this are immense. Every bit as large as the steam and oil revolutions before it.

The second shift is in robotics. Any and every repetitive function in the economy is going to be inhabited by a robot. This should not be feared. It will liberate humanity from the menial.

There are two types of functions that will persist. A builder or tradie will still be in employ given the complex problem solving and subtle biological functioning that they utilise every day. Everybody else will be required to move up the knowledge value chain. There, they will earn more so there is no cause for fear.

That’s the key. Technological advancement destroys some jobs but the productivity gains that come with it lift incomes for both capital and labour, creating demand and investment in new and more efficient segments. Everybody gets richer over time.

This brings us to the third technological shift, an amalgam of the first two. In the next decade, transport will transform radically. Most people will no longer need to own a car. Instead, a self-driving fleet of vehicles can be anything you want whenever you want.

Electric cars and trucks driven by robots will take over our streets much more quickly than anybody thinks. And with it will come a staggering productivity gain as:

- 80% fewer vehicles are needed to service the same effective miles driven.

- The price of ownership can’t compete with crashing toll fares as the cost of labour is eliminated and power is next-to-free.

- Electrical efficiency decimates downtime and maintenance, while robots kill the road toll.

And let’s not get started on aircraft. Just over the horizon are solid-state batteries that will run jumbo jets.

In short, if you know where to look, technology is entering a new productivity golden age.

Demographics

As they say, demographics are destiny.

China’s One Child Policy, which was brought into effect in the early-1970s and is credited with preventing around 400 million births from 1979 to 2010, initially produced a population pyramid optimal to economic growth. That is, where the largest segments of the population were neither young nor old, but in the middle (i.e. working age).

However, the demographic blessing provided by the One Child Policy has turned into a curse, with the United Nations forecasting that the number of working-aged people to dependents in China is set to almost halve over the next 50 years. Accordingly, demographics will increasingly become a net drain on the Chinese economy as the dwindling share of working-age population is forced to support an ever-growing elderly population.

Indeed, the demographic situation facing China is almost a mirror image of that faced by Japan in the early-1990s – a period that was followed by three consecutive ‘lost decades’.

There is one more point to make. Chinese urbanistion has passed 61%. It is on its way to 70% and higher over the next decade. But the number of people shifted per annum to meet these goals is well past historical peaks. Peak urbanisation saw close to 25m people per annum moving. Now it is below 20m and falling. Given much of the build-out for this ongoing shift has been completed in advance, China is now building out urban environments at a pace for which there is no productive future. This is going to slow.

By contrast, demographics across the US and emerging markets are far more favourable owing to their younger populations and higher birth rates and/or immigration. Yes, these nations will also experience population ageing and rising dependency, but at a much slower rate than China. This means that demography will be a far bigger drain on China’s growth than most other nations.

The Australian satrap

Australia’s modern geopolitical history is that of the perpetual satrap. From British Empire outpost to the collapse of Singapore to American satellite ever since. We’ve spent twenty years toying with the notion of becoming a Chinese client state but that moment has passed. It is now all the way with the USA.

And thank god for it. What kind of sad little nation would give up the freedom that made it so rich and relaxed for higher house prices and commodity exports?

Within the changing structure of geopolitics and the global economy, Australia faces both great opportunity and threat. Iron ore will lose its currency in the years ahead as China slows structurally, if not acutely and in crisis. Very likely, our fossil fuel exports are also doomed as climate change accelerates, over a longer time span.

The accelerated decoupling from China ahead will be difficult. Very much more so as the moments of great power conflict arise, most obviously around Taiwan.

Yet, Australians are resourceful people. Never more so than when challenged. At such moments in history, we have reshored and rebuilt industries furiously like indefatigable ants. We will do so again as needed. The people will prevail despite the slump of Canberra into gangster liberalism.

As our dirt exports decline, climate change shapes as Australia’s greatest saviour, despite our best efforts to render “no” as an answer. We genuinely are a renewable superpower in the making. Both in terms of clean energy output and the energy-intensive industries so carelessly thrown offshore for decades.

As energy declines towards its zero marginal cost in Australia before elsewhere, and we find ourselves ever less friendly with a hostile China, these will make a comeback.

Cyclical winners and losers

Chimerica reversed

Amid the structural trends, the key to understanding the unfolding business cycle is that it is the reverse of the two previous during which American growth sagged while Chinese growth boomed.

Developed markets have learned their lesson. In the US, there is now a clear-eyed focus among monetary and fiscal authorities to put growth outcomes ahead of inflation concerns. Both the Federal Reserve and US Treasury have shifted boldly to regimes that seek to run the economy “hot”. Their goal is to lift wages for workers previously dislocated by globalisation.

Conversely, the Chinese development model has run out of puff. After a decade (and more) of overbuilding, it faces a chronic problem of over-indebtedness, falling productivity, and stagnating growth. It has tried with fits and starts to address this since the rise of Xi Jinping but with limited success.

The problem is, every time it slows credit to misallocated sectors, wider growth slows sharply as well. The illiberal gangsters that have benefited so fulsomely from the old model scream blue murder. The CCP fears mass unemployment leading to insurrection. Spooked, it has repeatedly reversed out of the structural reforms needed.

Yet, if it does not undergo the needed structural reforms to higher-value-added growth and consumption, Chinese growth will stagnate completely and the CCP faces an even more difficult future.

So, China has embarked on another round of structural reform. The new Five Year Plan was explicit about shifting resources from unproductive building to more productive services and technology.

Right now it can afford to do this, and drive the reform effort further than previous iterations. Thanks to the shift in the US (and less so in Europe) towards supporting their own growth profiles at higher levels for longer, China will enjoy a strong external sector. It is also investing heavily in its new economy. So the fading old economy has two major growth offsets.

This is unlikely to be smooth. We can expect China to hit the brakes and then accelerator again for construction as growth slows too much. But, for now, and while the global economy recovers for several years at least, the brake is being progressively pushed.

Moreover, beyond a few more years, the simple truth is China is running out of stuff to build because it is running out of people to move.

Europe

The European economy remains a perversely export-driven basket case. The Eurozone economy is the largest continental economy in the world. Yet it operates like a tiny mercantilist state, ruled over by Northern European disciplinarians. This makes it a gigantic parasite fastened to global demand growth.

There has been a minor shift amid the pandemic towards supportive fiscal deficits but these might be considered barely sufficient to hold the currency bloc together.

Europe will bounce out of the pandemic as it eventually delivers enough vaccines and will enjoy a year of catch-up growth but that will soon fade as any kind of material growth driver for the global economy.

Europe and particularly Germany are simply too exposed to the Chinese growth engine for their own good and as it slows so, too, will they.

Australia’s triple shock

We have already seen that the Australian economy will weather its imprisoned pandemic and vaccine failure well. Both will cost us a lot more money than they should have but that’s water under the bridge. Ahead, the Australian economy will slow into weak growth as its post-COVID catch-up phase passes.

Property has another year or eighteen months to blow off before APRA pulls the pin on it. What follows is another drift in prices for a few years. Forget rate hikes, the RBA is more likely to have to cut.

The major reason is China. Its accelerated cyclical slowing is focused upon steel-intensive growth. Iron ore prices will fall a long way as demand fades while supply returns. Vale’s normalisation and new supply from every corner of the earth will arrive owing to the extreme price signal today.

As described above, the Chinese need to restructure, and that will set the course of iron ore in trend terms. But Beijing will also see iron ore prices crashing upon Australia as a cherry on top. Indeed, the strategic imperative to move China’s most important commodity supply chains out of the American liberal empire means that there is a risk of policy intervention to accelerate the collapse. Either via state-sponsored investment in alternative suppliers or price controls.

A second China shock is looming as well. As the global economy reopens, Chinese tourists and students will not return in the previous numbers. Bilateral nations are too fraught.

As iron ore tumbles, house prices stall, and the immigration drivers of growth in the last cycle fail to rematerialise, the Australian dollar will fall a long way. How far will depend upon how we respond.

If the RBA cuts, we could head into a circumstance akin to the late 1990s when Australian yields lagged the US by so far that the AUD fell below 50 cents. Or, a new government might unleash fiscal spending and the dollar not fall quite so far.

The tumble in the AUD won’t happen all in one go or without crisis. As said, Chinese restructuring has always been an ebb and flow affair, and periodic pops for iron ore are likely. Even if the master trend remains down.

The best sectors for investment will be in renewable energy. Despite our own worst efforts, the great transition will march on. The assets are just too good and it is now a matter of economics, not policy. All Canberra is discussing these days is how much to slow it down.

Outside of that, the reshoring and technological trends discussed above will be very slow to arrive relative to other nations as we do our best to protect the unprotectable.

In short, another lost Australian decade is in the offing and it won’t end until the AUD falls much further and stays down for years to trigger a rebuild in long-forgotten tradeable sectors.

Emerging markets to hell

In one sense, the outlook for emerging markets is good. Balkanised global supply chains will move into strategically friendly blocs. We can see this today in a furious re-alignment of semi-conductor production. For other widgets, the production that exits China will most often shift to other low-cost emerging markets within the liberal bloc, in Asia and Central America.

On the other hand, the outlook for emerging markets is poor. First up, they can’t get vaccines. Those that have are mostly from China, and there are efficacy question marks over these. Emerging markets will be the last to recover from the endogenous impacts of the pandemic.

Worse, the outlook for commodities is weak. Wall St believes that US stimulus and growth leadership will trigger an onslaught of demand for copper and other climate-related metals. The truth is the stimulus for hard assets is moderate. Most of it targets human development. Today’s big bounce in commodities is short-cycle catch-up growth.

More likely is that, as China slows and its demand falls, plus recycling of vehicles and other widgets booms with electrification, we’ll need fewer commodities, especially iron ore and copper.

Chinese demand is just too big and US demand is just too small.

In other words, just as emerging markets emerge from the pandemic, they’ll be hit by terms of trade shocks similar to what’s ahead for Australia via iron ore. Emerging markets are huge commodity exporters.

Worst of all, emerging markets face a battery of difficulties in the reverse Chimerican new world order. In this world, Chinese demand for emerging market exports falls every year, along with CNY, and the US dollar rises as well.

This puts fundamental pressures on emerging market external accounts just as financial pressure comes to bear on external borrowing.

Think of the Asian Financial Crisis as an analogy, which transpired as US growth boomed into the millennium and the US dollar thundered. 2015 is another example, as emerging markets were crushed between Chinese restructuring and a tightening Federal Reserve.

With the US leading the cycle, its growth and inflation exceptionalism will make it difficult for the Fed to turn tail and bail out emerging markets, as it did on both previous emerging market crisis occasions. At least, not before major contagion back into US markets.

These crises are not imminent. Post-virus reopening and catch-up growth are ahead first. But they are already upon the horizon as China tightens post-COVID policy and the US opens the fiscal pump.

Assets

Debt

Developed market debt securities have enjoyed a secular bull market as underlying economies were hollowed out by globalisation and inflation fell away. But that paradigm is now breaking for the structural reasons described above.

For fixed interest securities the implications are profound. Inflation so long quiescent is rebounding. It has a long way to run before it becomes any kind of sustained threat, and need not be such at all if well-managed. But the bottom is in and the secular bull market for developed market debt is over.

Ahead is no sudden, giant back-up in yields to blow up the global economy. Rather, we’ll see a series of slow cycles of inflation bouncing along the bottom as reshoring, carbon mitigation, fiscal support and rising wages for the displaced workers of globalisation.

Debt will need to be traded with a higher frequency than in the past to catch these ebbs and flows.

Houses

While the pandemic has lasted, a new house price boom has taken hold globally. This is driven purely by extraordinary policy support. Direct fiscal transfers to lift income, zero and negative interest rates, easing rules for banks, are all working their magic. This will last for a few years as western science kills off China’s virus.

There is more ammunition in the chamber to support these assets so there is no imminent reckoning. A long, flat trend to higher inflation will be encouraged by central banks, not snuffed out by imminent credit tightening. Corrupt politicians will constantly intervene. But the best of times for these assets is right now. Ahead they will be challenged on and off by the new secular forces of deglobalisation. Higher (if not threatening) inflation, geopolitical conflict, aging populations and deleveraging present a less seamless outlook than the last thirty years of non-stop cheapening credit.

And there are emerging risks abroad that none of us could imagine previously. War in Taiwan would crush Australian income as Chinese exports cease. House prices would tumble even though the AUD will absorb some of the blow.

Then there is the end of immigration. Virtually no Australian outside of the Morrison cabinet and a few liberal gangsters wants to see it ramp up again. It is such political poison that even the woke Australian Labor Party is turning against it.

The local leadership class will be last to embrace the renaissance of liberalism underway in the free bloc of states but come it will as Australian workers matter again.

Equities

Global equities are very expensive today, held aloft by intense policy support. Price/earnings multiples will have to come down over time. The question is how?

A global profits boom is underway and will put a decent dent in the multiple by growing the earnings. For the time being, global economic reopening and US economic exceptionalism plus policy largesse are driving a historic bull market that has further to run.

But there is obviously a risk that post-pandemic, capital values will fall. There are several potential culprits for this.

Policy error is the major risk. If fiscal or monetary authorities get spooked by inflation then a sudden repricing or bear market is possible. The highest risk of this today is in China as it tightens and shakes out its heavily indebted construction-related sectors, as we have already seen repeatedly in rising SOE defaults and junk debt yields.

Second, the trials of emerging markets more broadly amid a US dollar bull market shapes as a major stress test for valuations a year or two out.

Third, we could see an acute geopolitical crisis arrive in Taiwan or elsewhere.

Fourth, we might lose a handle on the pandemic again.

These are all risk not base cases for a year or two. As well, you will note that all of the major known risks to the bull market are especially pointy for Australian assets. This is why the Australian dollar is stuck under 80 cents instead of roaring above 90 cents already, as it would have done in the previous two cycles with iron ore prices so high.

Conclusion

Australia has had a very good pandemic but normalisation will bring back all kinds of structural challenges to growth that existed before it, along with new ones.

These include household over-indebtedness leading to early (macroprudential) tightening for property, challenging household balance sheets despite high savings. Over-exposure to China will go through another convulsive unwind, challenging income. Our largest resource sectors are overbuilt not underbuilt, challenging investment. The great immigration fraud is broken leaving massive oversupply in all kinds of services sectors. Badly hollowed out tradable sectors offer no offset until the AUD is much lower for much longer.

With the exception of renewable power, we will be the last to benefit from the technological revolutions to come, owing to the liberal gangsters that own our politicians.

Once we get past the policy supports of the pandemic, most Australian assets have little growth underpinning to drive them forward. Only bonds appear to have value because global markets have not yet differentiated our yields to match this gloomy outlook.

Conversely, the growth outlook for some other developed markets is very good in the short and medium term. Led by a revitalised progressive American liberalism with years ahead of exceptional growth.

The conclusion for investors is that offshore assets beckon with better returns and greater structural tailwinds. Further, the risks are also lower. Intermittent crises invariably result in a falling AUD, which cushions any downside from falling stock markets.

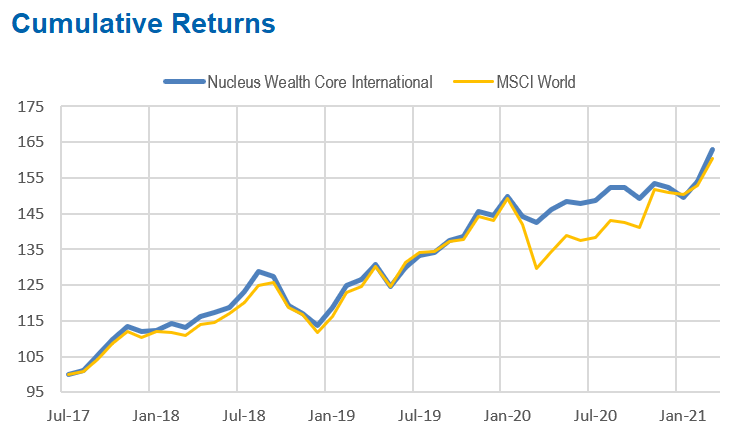

David Llewellyn-Smith is Chief Strategist at the MB Fund and Nucleus Wealth. The MB Fund/Nucleus Wealth Core International fund is one way to get quality international equities exposure. The fund has outperformed the MSCI World index for four years with consistently lower volatility:

If you are interested in knowing more about the fund then contact us below: