The latest ABS Labour Force survey painted a deeply mixed picture of the job market.

On the one hand, this single print presented a compelling picture: a substantial increase of 42,200 new jobs, all full-time in net terms, and a robust growth in hours worked.

However, a longer view reveals a decidedly more challenging picture.

As noted by Sydney Morning Herald journalist Shane Wright on Twitter, the economy has only created 82,000 jobs since April, including the bumper October print.

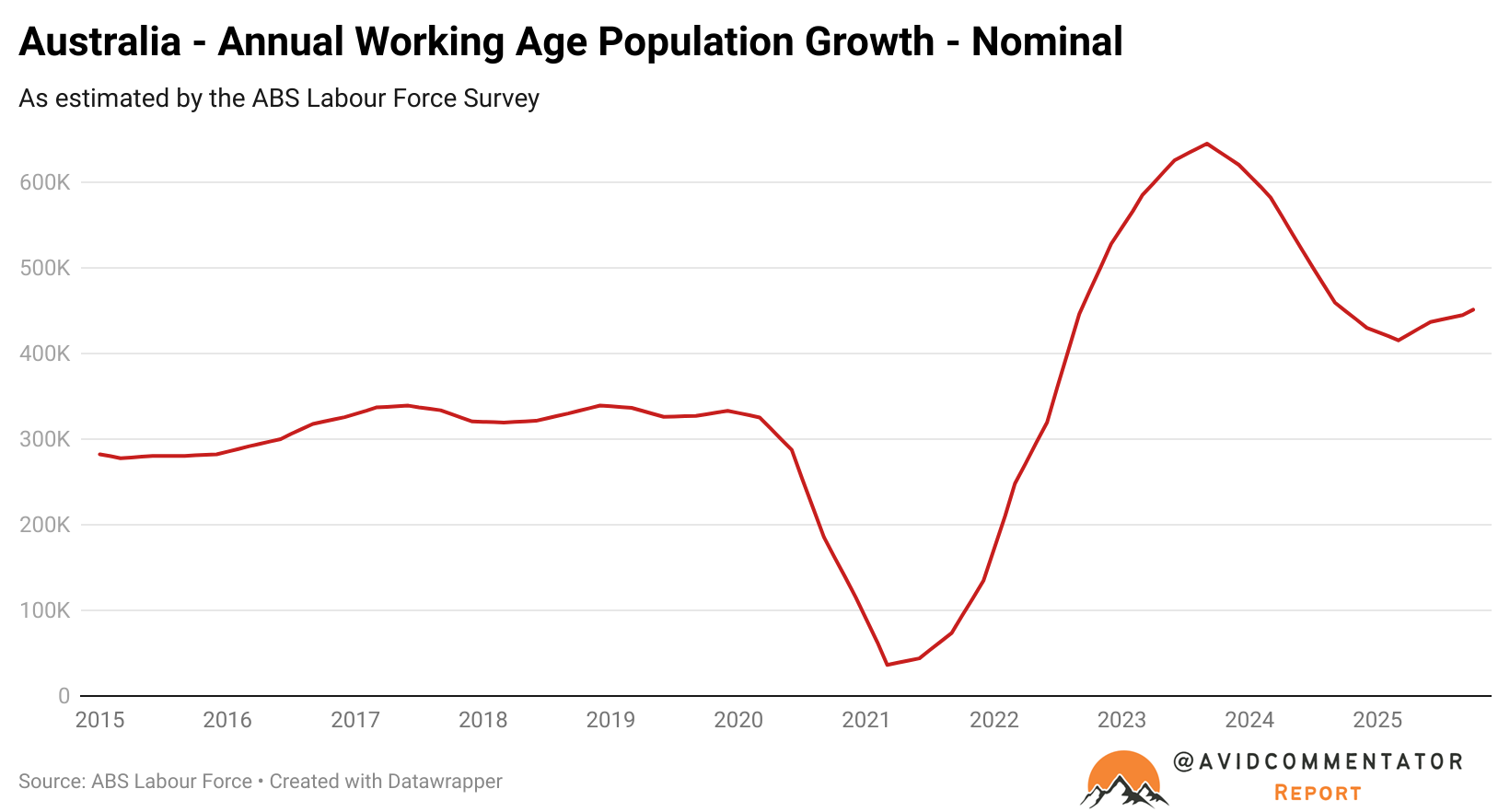

While this is not a horrible level of job growth over an average six-month period, it has arrived at the same time as Australia’s working-age population and, by extension, the labour force are still growing swiftly.

As a result, the job growth is not enough to prevent unemployment from rising.

This brings us to an interesting question: where could this demand for additional labour be coming from?

The true gold standard for labour market data in Australia is the ABS Labour Account.

The problem is, the current Labour Account data we are working with only covers up to the end of June and we won’t have the updated snapshot for the September quarter until the middle of December.

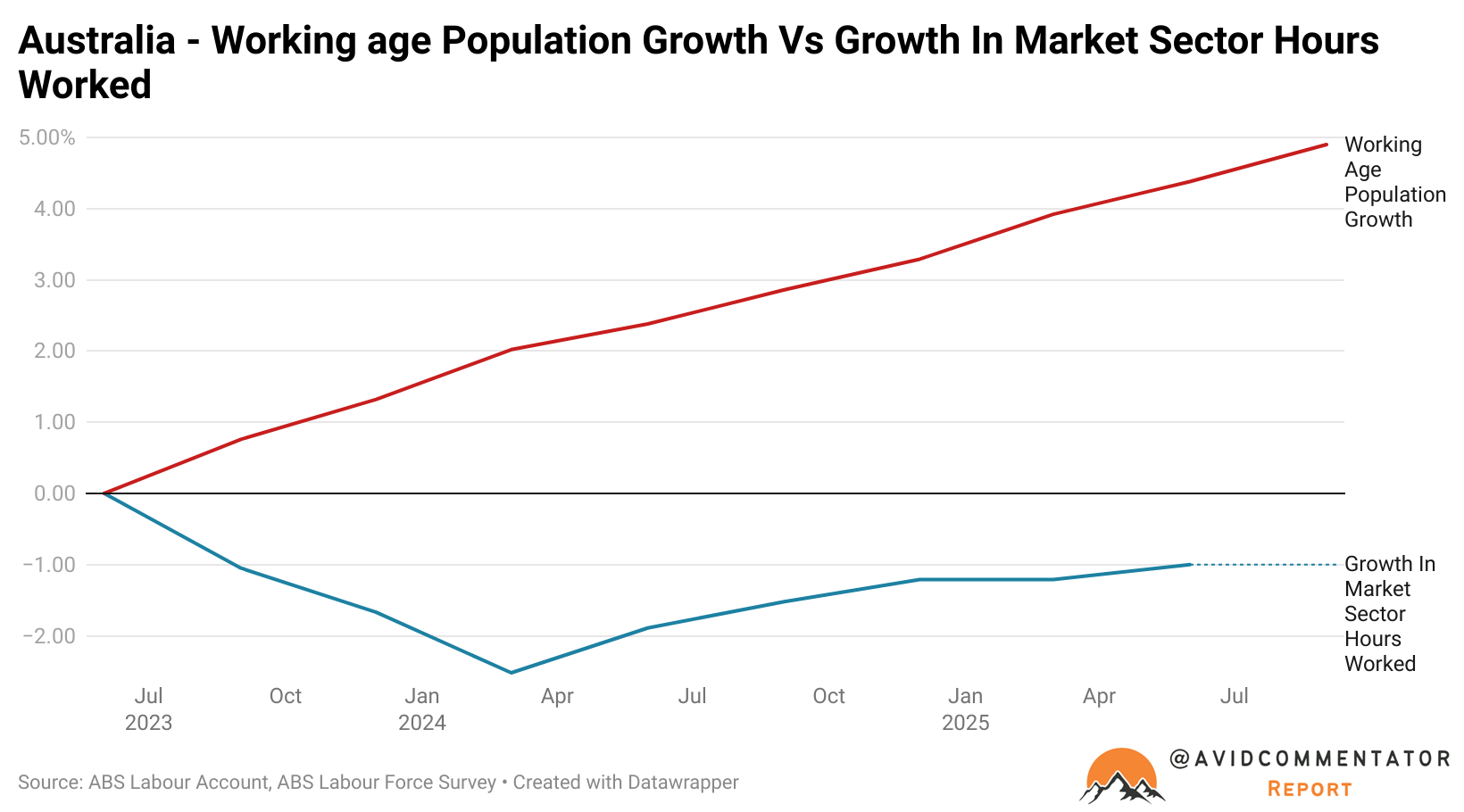

Based on the figures from that data, growth in hours worked for the market sector has been sub-par for much of the last two years.

While there was something of a recovery from a lower base from the end of Q1 2024 to Q4 2024, since then the growth in the Labour Account has been weak.

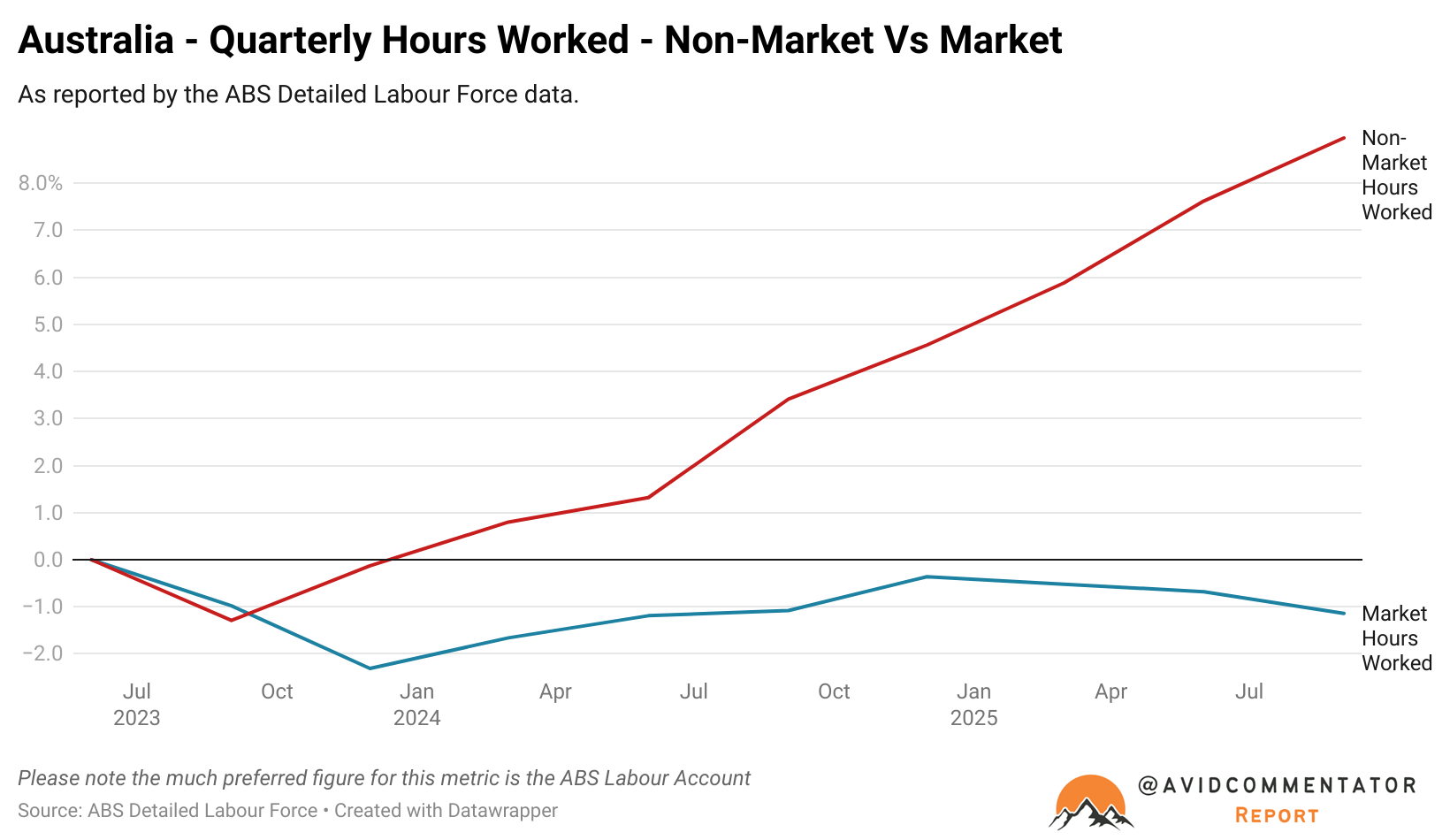

If we step back and take in a broader view of hours worked across the economy from the ABS Detailed Labour Force data, it reveals that hours worked grew by just 0.05% in the September quarter, the weakest performance in growth in hours worked since the December quarter of 2023.

The ABS Detailed Labour Force data also possesses a breakdown of hours worked in the non-market sector (i.e., public administration and safety, education, and healthcare and social assistance) versus the market sector (all other industries). But the ABS has emphasised on multiple occasions that the Labour Account data is the significantly more accurate measure of this sort of metric.

So it’s far from perfect as a distributional indicator, but it is at this stage all we have until the middle of next month.

Examining hours worked in the market sector over the last 12 months reveals that growth stalled out in December last year, and since then the number of hours worked has continued to contract.

Meanwhile, the number of hours worked in the non-market sector has marched ever higher.

It shares this characteristic with the Labour Account data, where despite more or less flatlining levels of job growth in those sectors, hours worked has continued to grow.

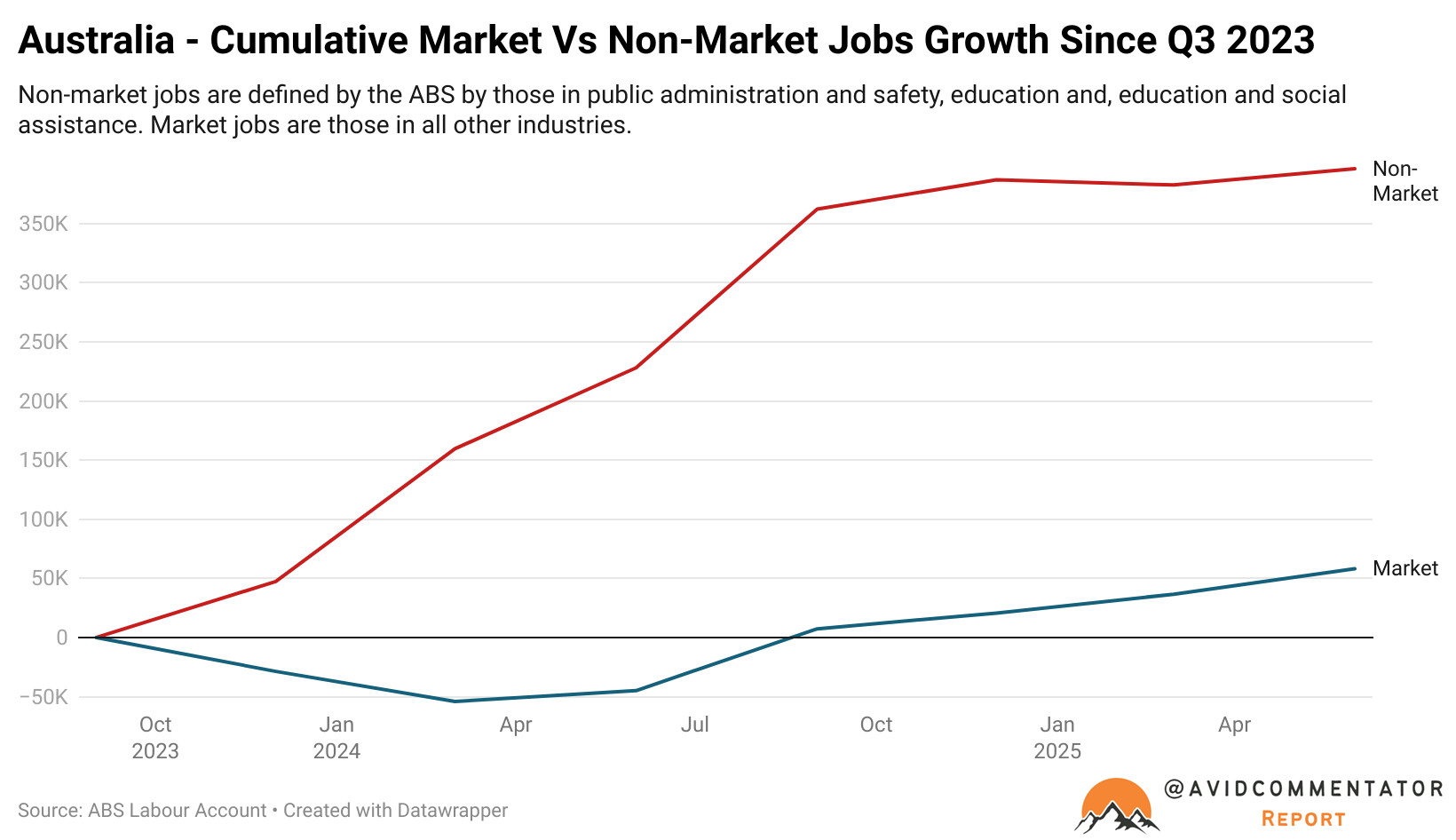

This leaves us wondering whether the purported robustness of the Australian labour market is again being heavily driven by taxpayer-funded employment growth.

Based on recent experience, we shouldn’t be surprised.

Ultimately, the defining question of our time for the labour market may be how big can government get as a proportion of the economy before that impulse supporting the labour market runs out of steam.

At some point, the jig will be up.