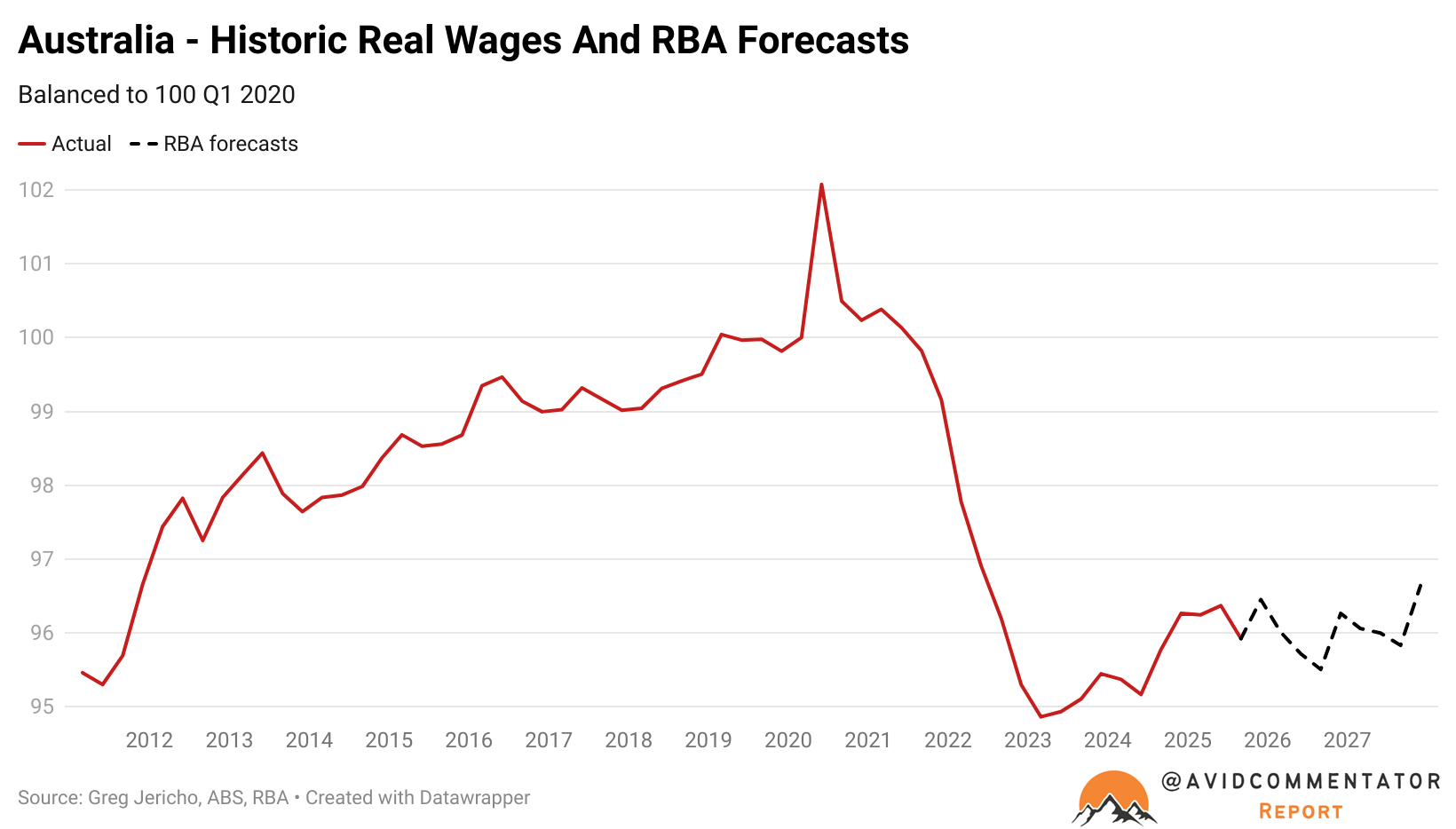

In the second last line of the RBA’s exhaustive forecasts out to December 2027 was their projection for real wage growth in year-on-year terms at 6-month intervals.

According to an analysis from Greg Jericho, the policy director at the Centre for Future Work, what they have projected is effectively two separate recessions for real wages in technical terms.

One starting in the March quarter of 2026 and lasting for three quarters, and another starting in the March quarter of 2027 and lasting for three quarters.

In the first, real wages are expected to contract by a total of 0.97%, followed by a contraction of 0.45% in the second.

Overall, at the end of the RBA’s forecast period in December 2027, real wages are expected to be just 0.28% higher than the post-pandemic peak recorded in June this year and end up roughly where they were in the December quarter of 2011.

While real wages were growing prior to the pandemic, their rate of growth in the final years prior to the pandemic was anaemic

Between June 2016 and the final data point unimpacted by the pandemic in December 2019, real wages grew by just 0.35% cumulatively over that three-and-a-half-year period.

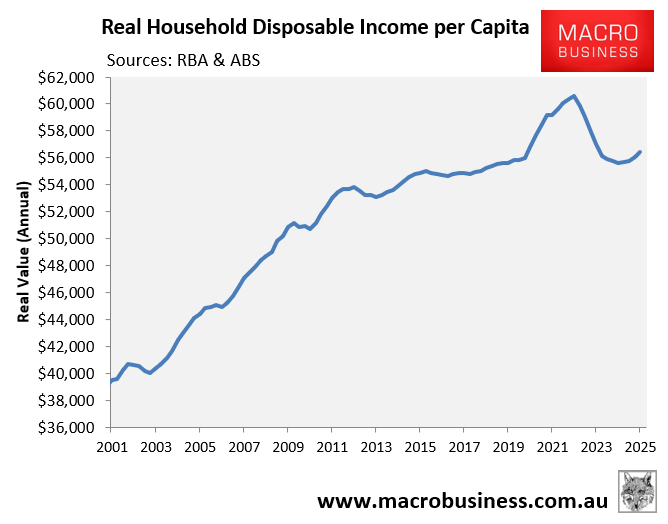

This dismal performance is not isolated to real wages; when looking at real household disposable income per capita, which is often referred to by economists and the media as “living standards”, there is a similar trend of relative stagnation from the conclusion of the mining boom.

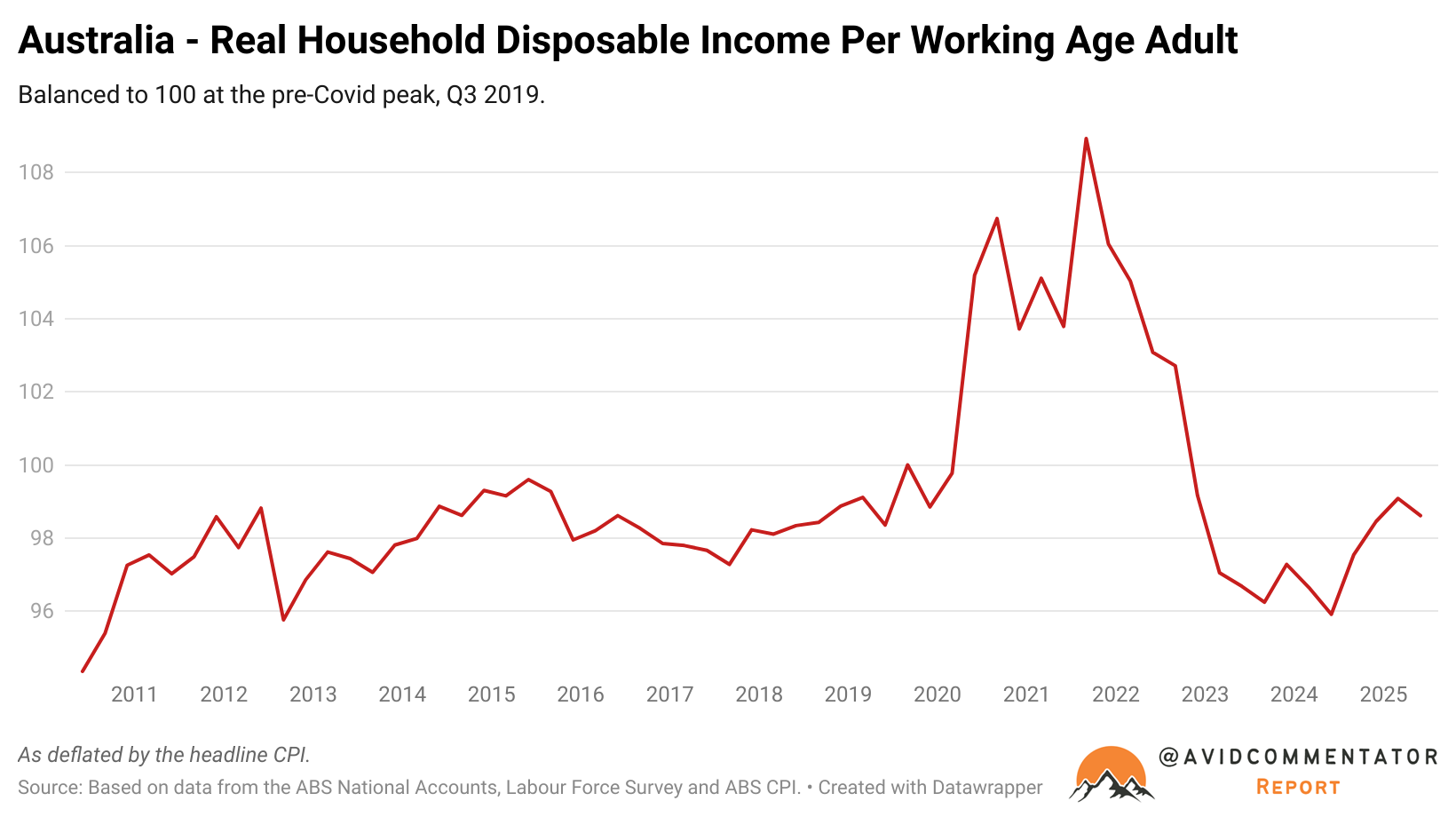

However, once the figure is deflated by the working age population and not the overall population, it reveals that living standards have not improved above where they were in 2012.

The reason why this is arguably the more relevant metric is due to the fact that what we have effectively seen in the era of a ‘Big Australia’, is children getting replaced by fully grown adults, which artificially pushes real household disposable income per capita higher.

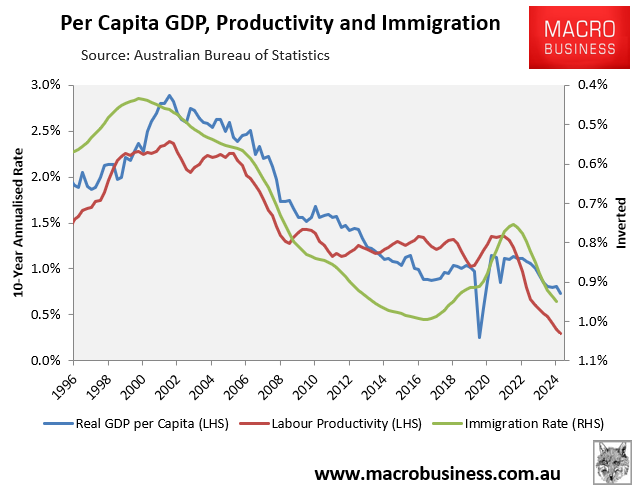

Meanwhile, productivity continues to nosedive to record lows by some metrics, leaving the rate at which wages can sustainably grow without being inflationary at an uncomfortably low rate.

In the words of HSBC Chief Economist Paul Bloxham:

“The economy is already growing at, or even a bit beyond, its speed limit.”

“The problem we’ve got is weak productivity, and so just a little lift in growth and once again, we’ve got an inflation challenge.”

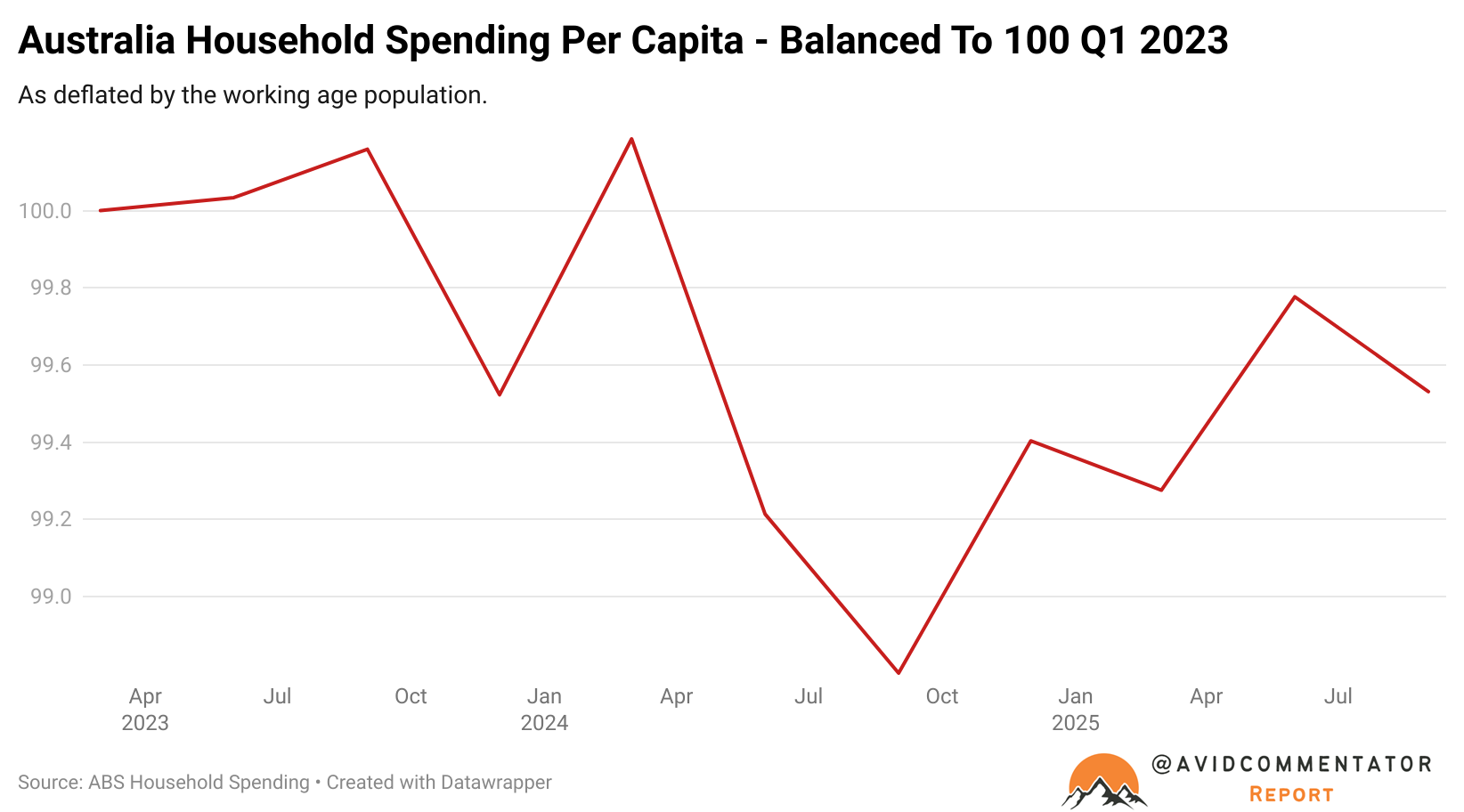

Yet when household spending per capita is viewed through the same aforementioned working-age population lens to adjust for population composition, households are spending less today than they were two and a half years ago.

Ultimately, policymakers face some very serious challenges on the road ahead.

Attempting to balance economic growth, interest rates, inflation, and migration will be perhaps the most difficult task of their professional lives, and the stakes could scarcely be higher.