Australia’s housing market depression

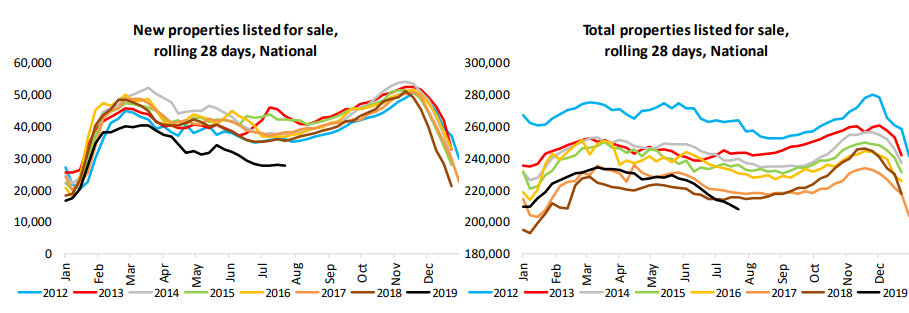

When Australia closed out the 2017 calendar year, the total number of properties listed for sale reached a level considered, at the time, deeply depressed.

With just a little over 200,000 homes listed for sale, it was dramatically below what had become normal in the early to mid-2010s, when the 220,000 to 240,000 homes for sale at year’s end were roughly par.

Source: CoreLogic

Fast forward to the present day, and this is a level of listings and options on the market that prospective buyers would kill for.

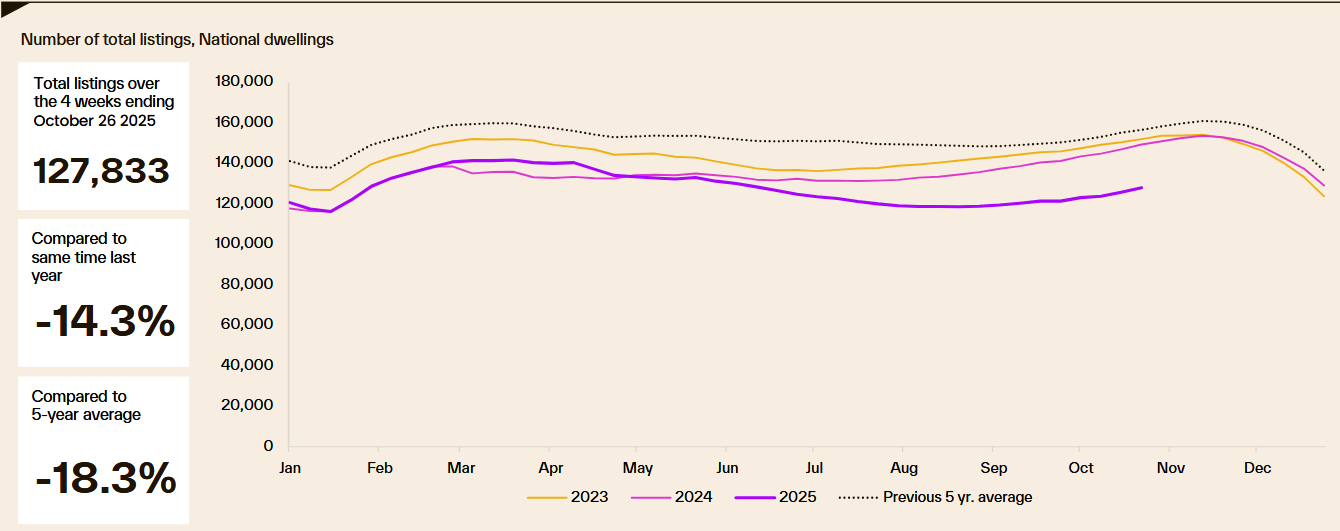

As of the latest from Cotality (formerly CoreLogic), there are just 127,833 properties for sale nationally.

Even compared with the deeply depressed five-year average, which encompasses multiple years of the pandemic and the drought in stock that followed, total listing numbers are down by 18.3%.

Source: Cotality

While the later months of 2024 and early 2025 brought hope of a recovery in total stock on the market, which had returned to 2023 levels, in reality the continuing rental crisis and the surge in demand from property investors to record highs has delivered a shortage of stock on the market not seen in at least a decade.

This factor is a largely appreciated driver of the COVID-era property boom and continues to support the market to this day.

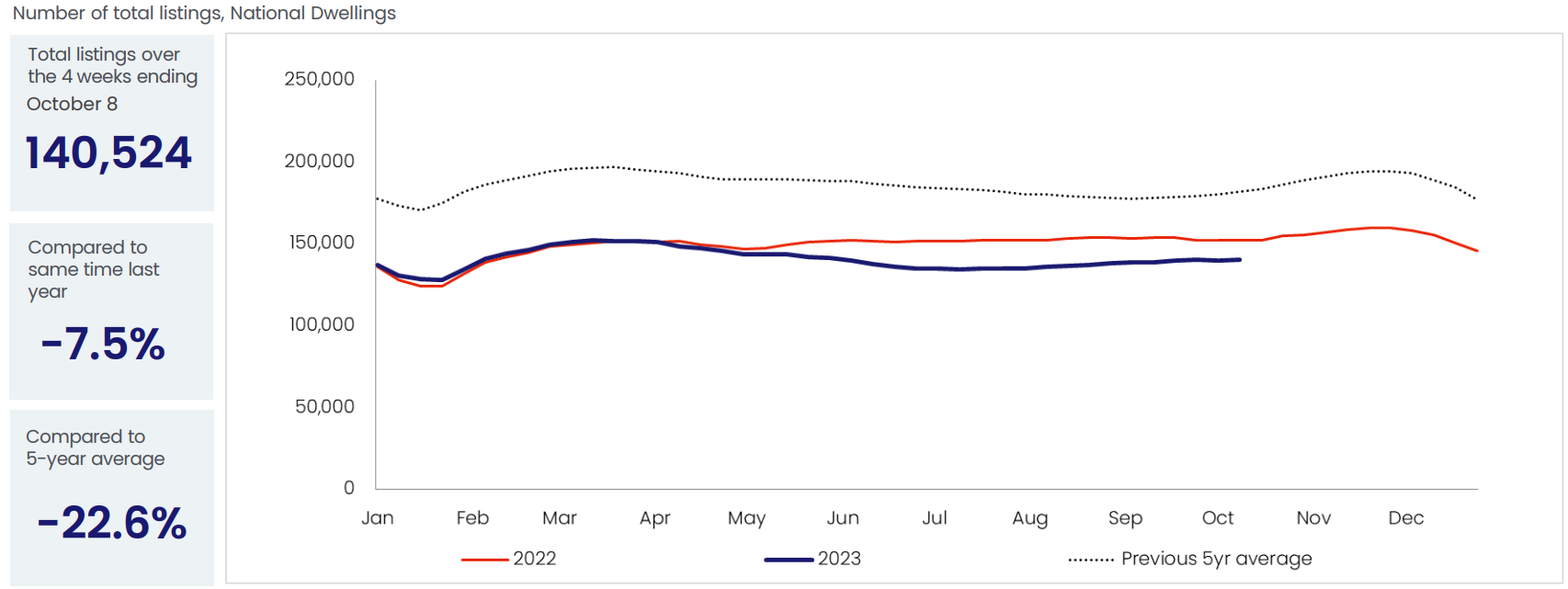

As lockdowns and Covid restrictions acted as a brake on new listing numbers, demand surged as Australians sought greater space or different surroundings.

But as listing numbers plummeted again and again, what happened next was simple economics: price growth.

Listings just kept dwindling even after lockdowns ended.

Source: CoreLogic

In short, the market was never allowed to recover from the shock of the pandemic.

Instead, it’s been one source of demand being added after another, while aging demographics play a significant role in reducing new listing numbers and act to stifle levels of turnover.

To be completely fair, it’s not like the federal government has made a secret of its desire for higher property prices.

In December of last year, Housing Minister Clare O’Neil appeared on ABC Radio to discuss housing issues.

Here is a copy of the key part of the transcript.

Interviewer:

Why don’t you want to see house prices drop? Because if you’re a young person looking at what’s ahead of you, you definitely want to see house prices come down.

Clare O’Neil:

Well, that may be the view of young people. That’s not the view of our government. We want to see sustainable price growth…

Interviewer:

But minister, if house prices don’t come down. Doesn’t that this system is stacked against young people. And it is just not going to work for them?

Clare O’Neil:

Our government’s policies are not going to reduce house prices and we want house prices to grow sustainably.

The Takeaway

What we have seen transpire over the last 5 years is, in many ways, an expression of the most basic fundamentals of economics.

The pandemic drove the amount of stock on the market to depressed levels, resulting in conditions favourable for price growth.

Coupled with the result of intervention after intervention, from a near-zero cash rate to the Albanese government’s 5% deposit scheme, it has never had the time it needs to recover as a balanced market.

The big question is: can a market with a more balanced level of supply support additional price growth or even the current price levels?