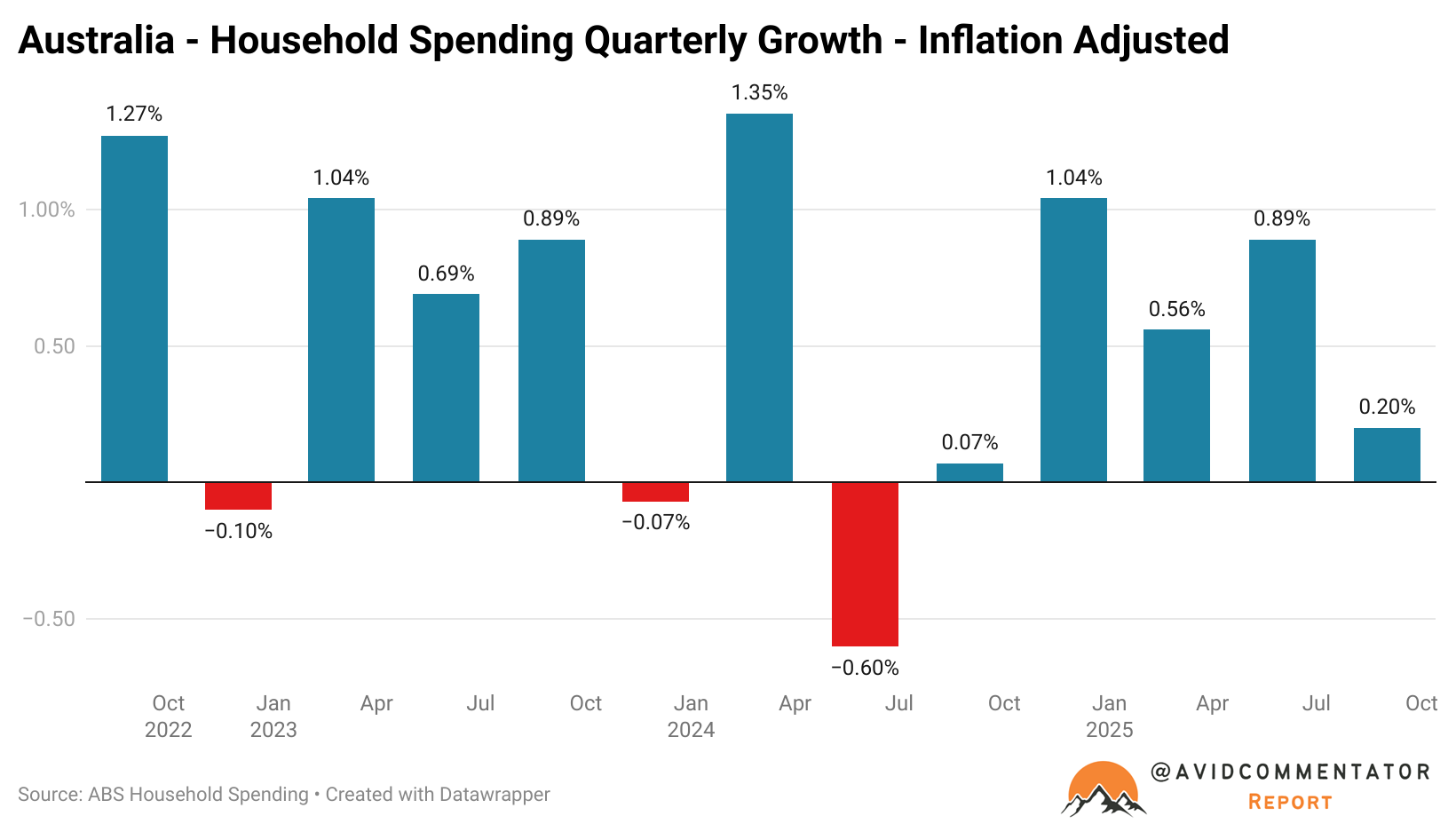

With the release of the latest ABS household spending data, it was revealed that in inflation-adjusted terms, households had only grown their spending by 0.2% in the September quarter.

This result was down significantly from the 0.9% achieved in the June quarter and the weakest result since September last year.

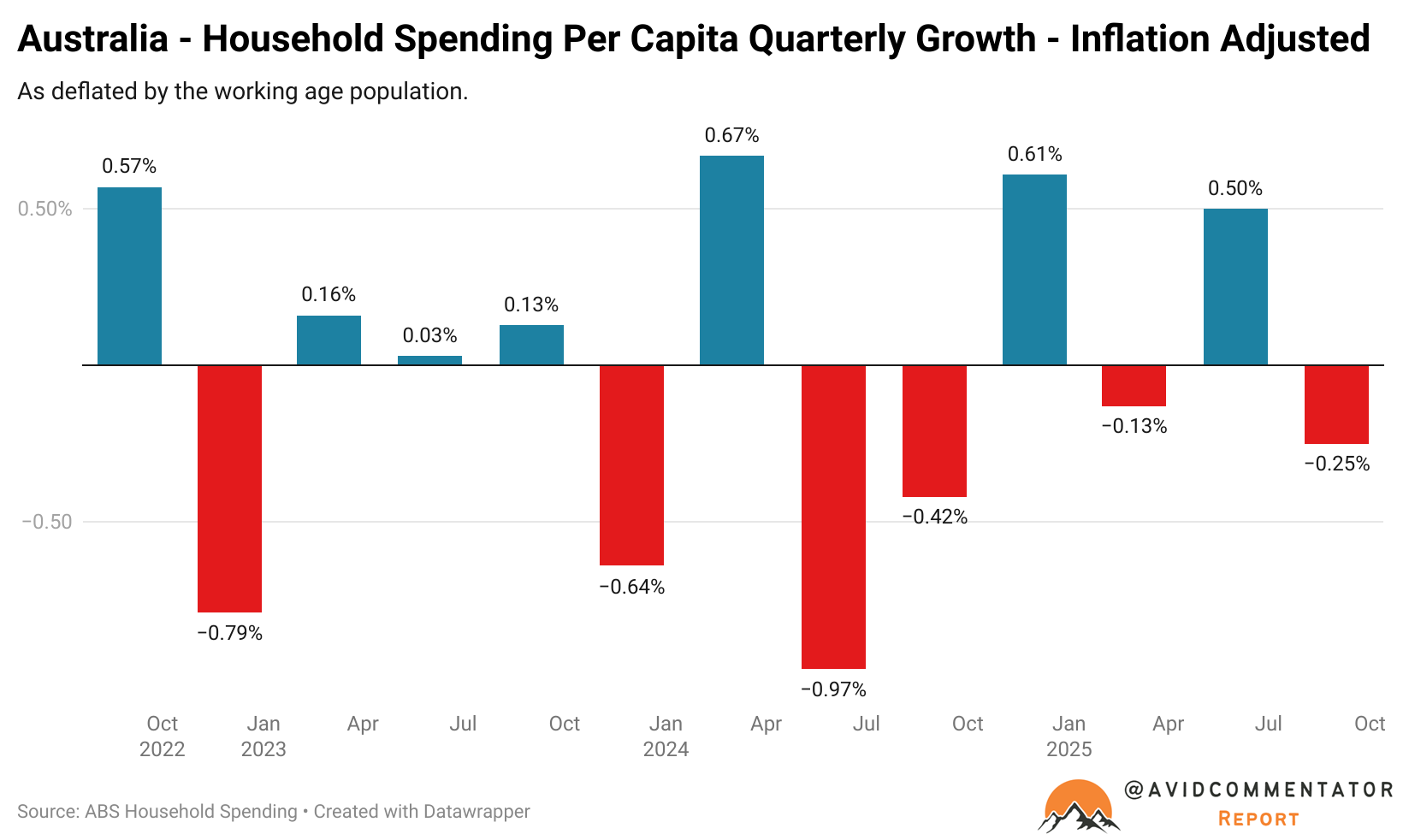

In per capita terms once deflated by the working-age population (which will be the metric referred to for much of today’s analysis), the news is even less favourable.

The quarter saw a contraction of 0.25%—the fifth contraction in the last eight quarters.

It is here that it’s worth taking a trip down memory lane, all the way back to December 2018.

This is where growth in household spending per capita stalls and this peak is not equaled again until June 2022, amidst surging ‘revenge spending’ stemming from the pandemic.

Between December 2018 and the latest data, household spending per capita has risen by just 2.61%.

If we consider the first quarter of 2023 as the true starting point for post-pandemic data, per capita household spending has fallen by 0.47%.

In short, households in aggregate have been going absolutely nowhere for the best part of three years.

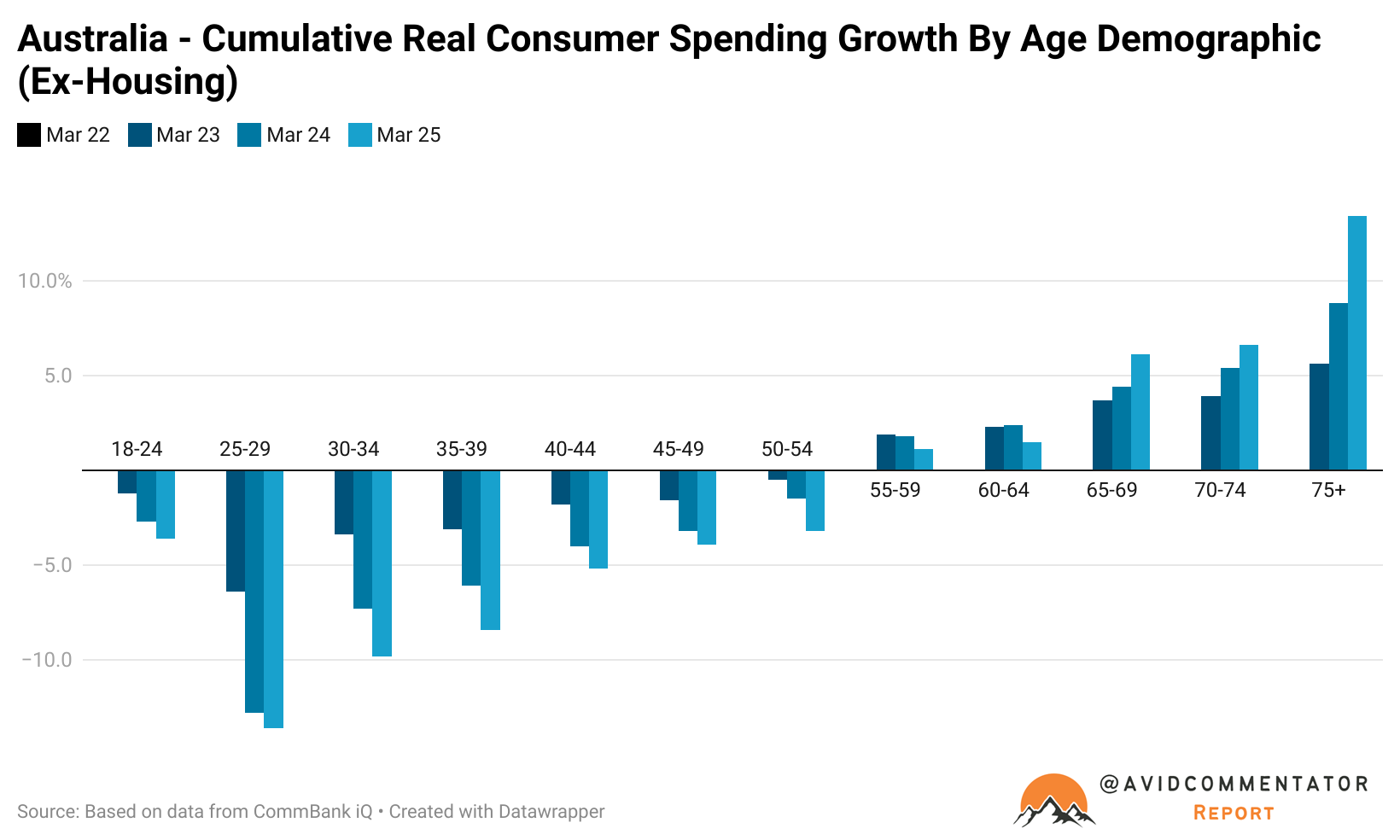

But this only tells part of the tale.

By looking at a breakdown of household spending growth (ex-housing) from CommBank iQ, it reveals that different household age demographics have fared dramatically differently.

For households aged 25 to 29, they have seen what is literally a technical depression in their spending growth in the three years of data on offer.

At the other end of the spectrum, the 75 and over demographic has seen extremely robust growth.

The Takeaway

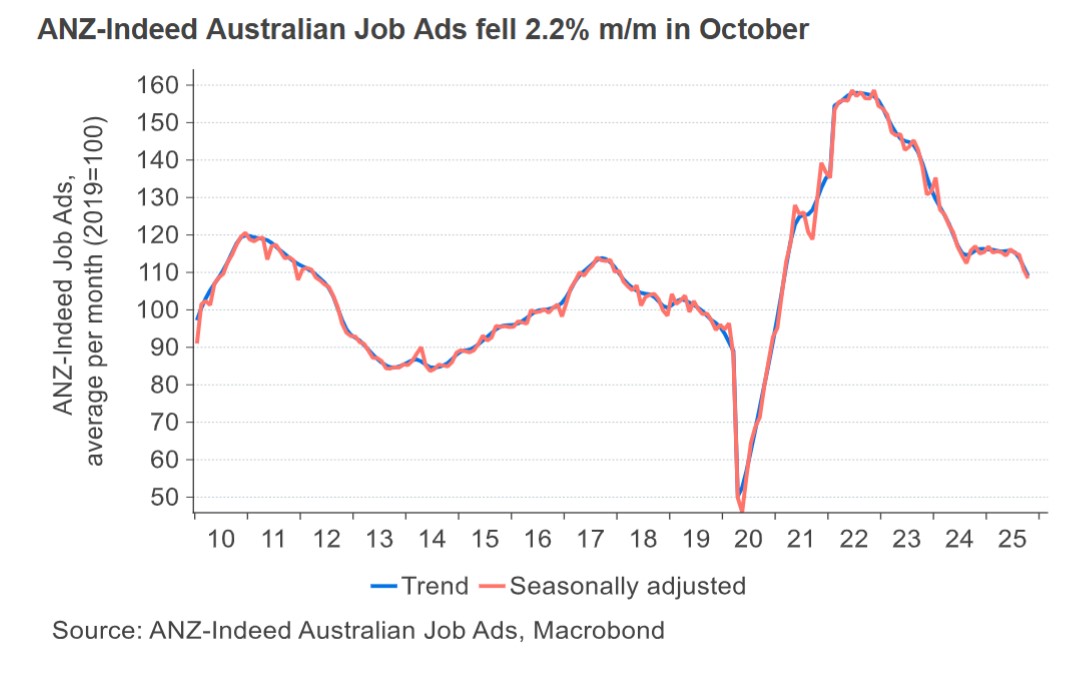

Amidst rising unemployment, declining job ads, and a dwindling number of expected rate cuts, risks are arguably rising that the Australian household sector is heading for stall speed, despite still extremely robust levels of working-age population growth, largely driven by migration.

The big question going forward is what would the Albanese government do about it?

If the reacceleration in population growth seen in the working-age population figures and national accounts is correct, then higher migration may already be playing a role in supporting the economy.

If that proves to not be enough in 2026, the government may require a different strategy in order to add more scaffolding to hold up an already heavily government-support-dependent economy.