Following the release of the ABS monthly inflation data for August, the outlook for interest rates held by various banks changed in a matter of hours.

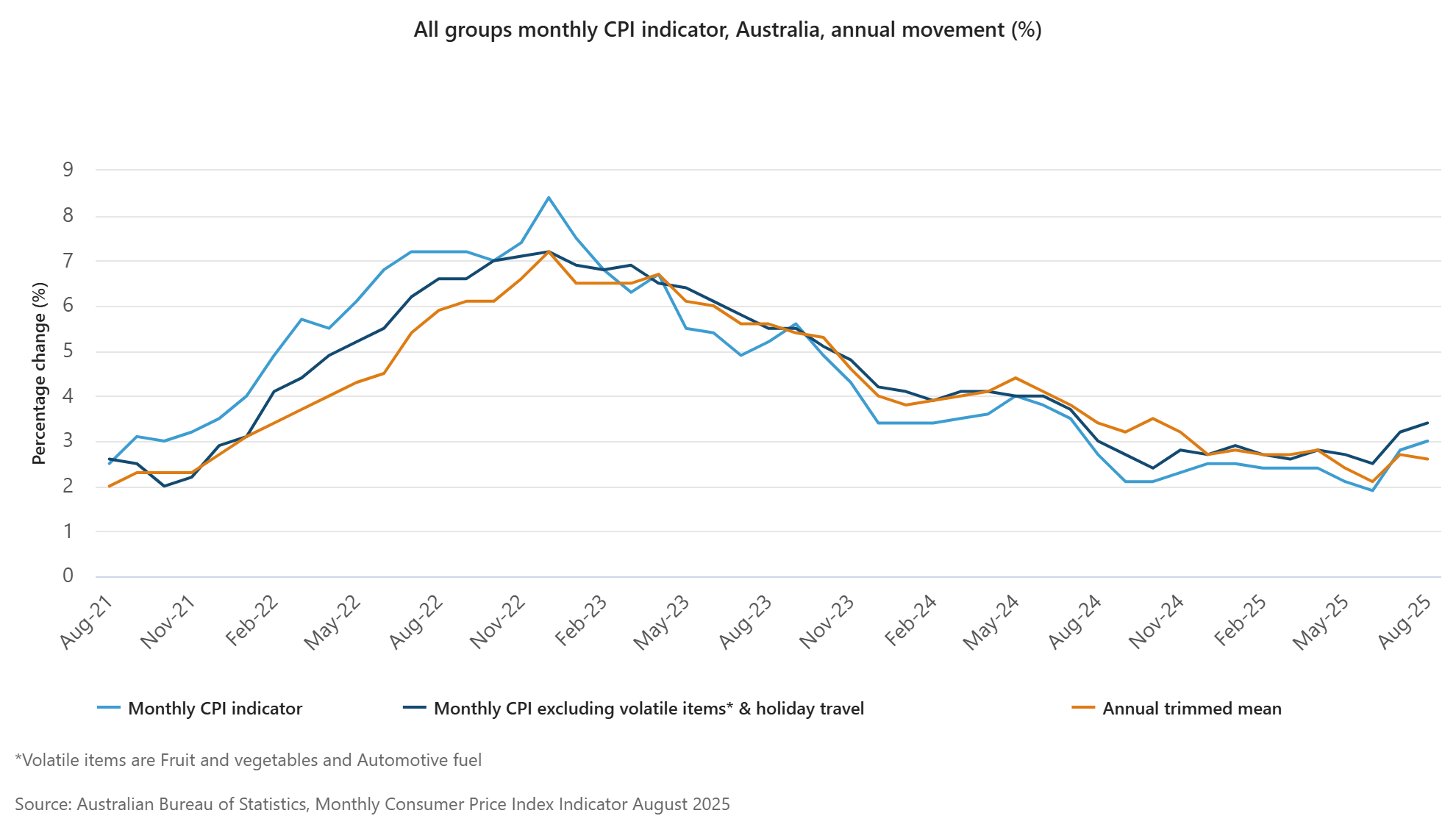

The figures showed that annual headline inflation rose to 3.0%, up from 2.8% in July, hitting the top end of the RBA’s target band for the first time since July last year.

Excluding volatile items and the holiday travel metric, inflation hit 3.4% on an annual basis, its highest reading since July last year.

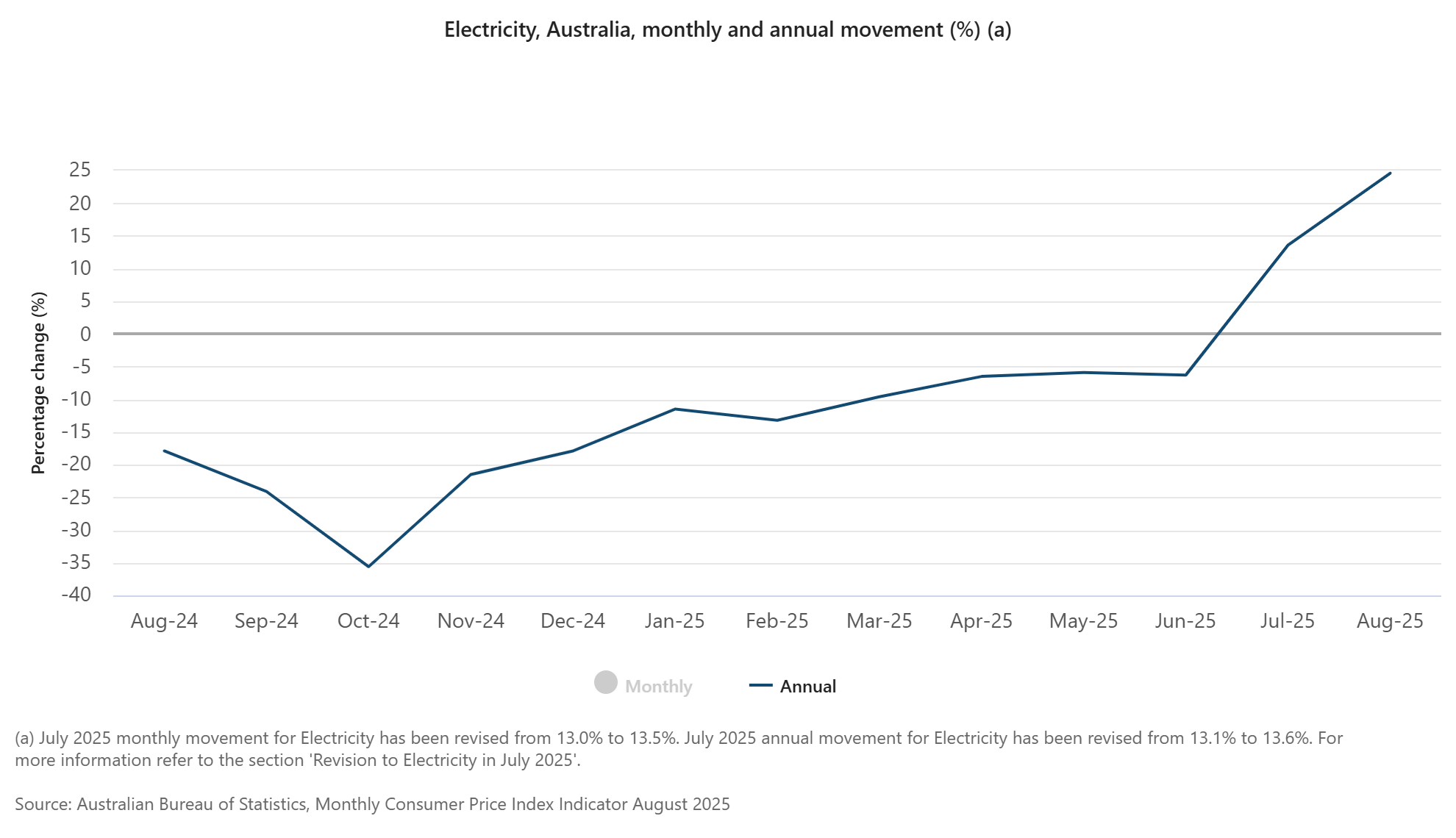

The trimmed mean figure performed better, registering at 2.6% year on year; however, this is due to the exclusion of the significant rise in electricity prices, as the positive effects of various subsidies are no longer reflected in the data.

As the various bank economists analysed the data, they quickly revised their outlook for rate cuts.

Prior to the inflation print, NAB had two rate cuts penciled in for November and February. It now sees the RBA on hold until May next year.

Deutsche Bank warned that the “trimmed mean is stickier than we expected”, noting that further rate cuts were delayed until next year.

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Bank warned that a November rate cut was no longer a “done deal” following the CPI data.

It’s certainly true that inflation is stickier than some anticipated, but the big question is whether or not it will be the sole defining metric of the current rate cut cycle.

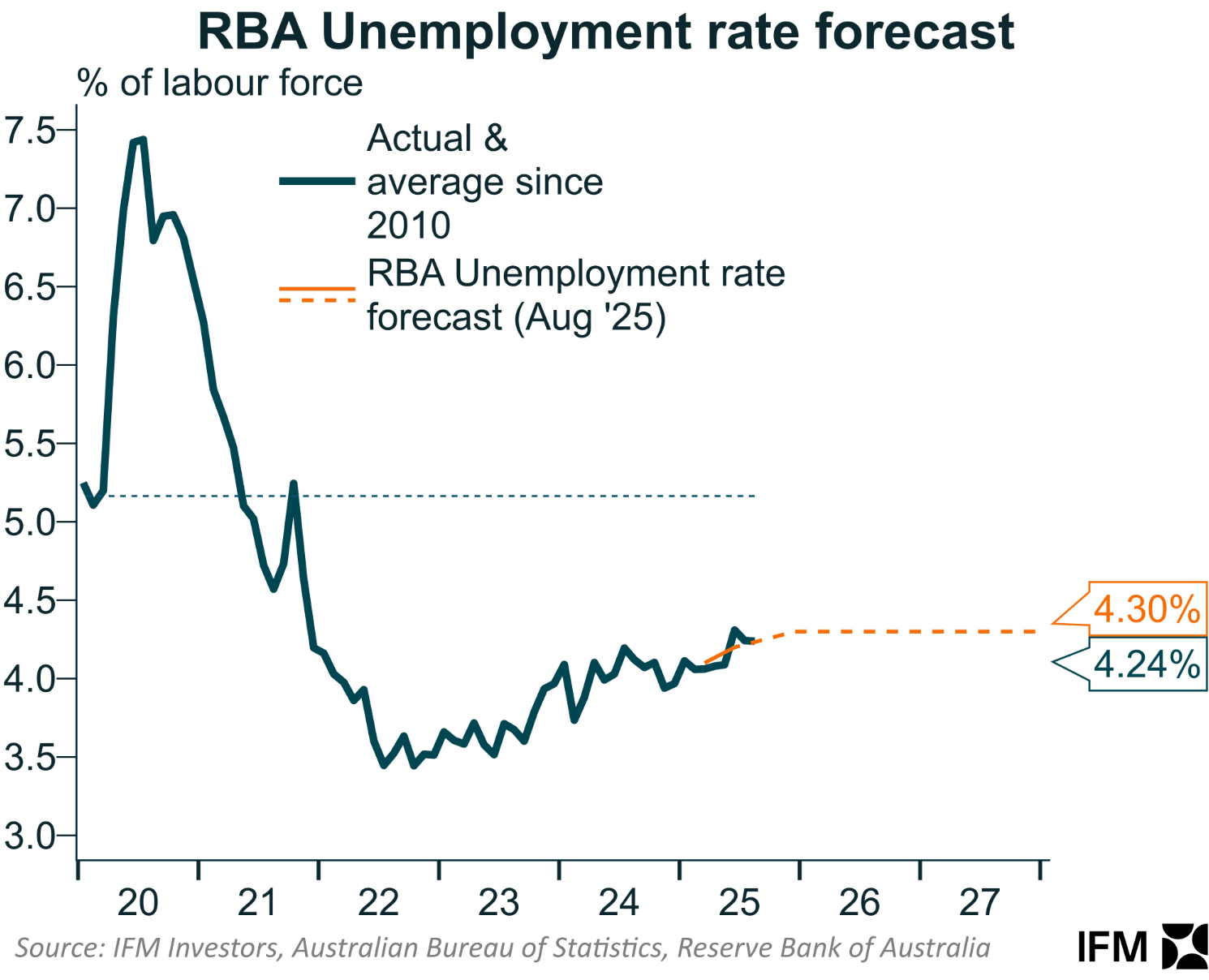

Currently the RBA has a peak in unemployment of 4.3% pencilled in all the way out to mid-2027.

Source: Alex Joiner IFM Investors

Yet a rise in unemployment of less than 0.1 of a percentage point would see that figure exceeded, if only slightly.

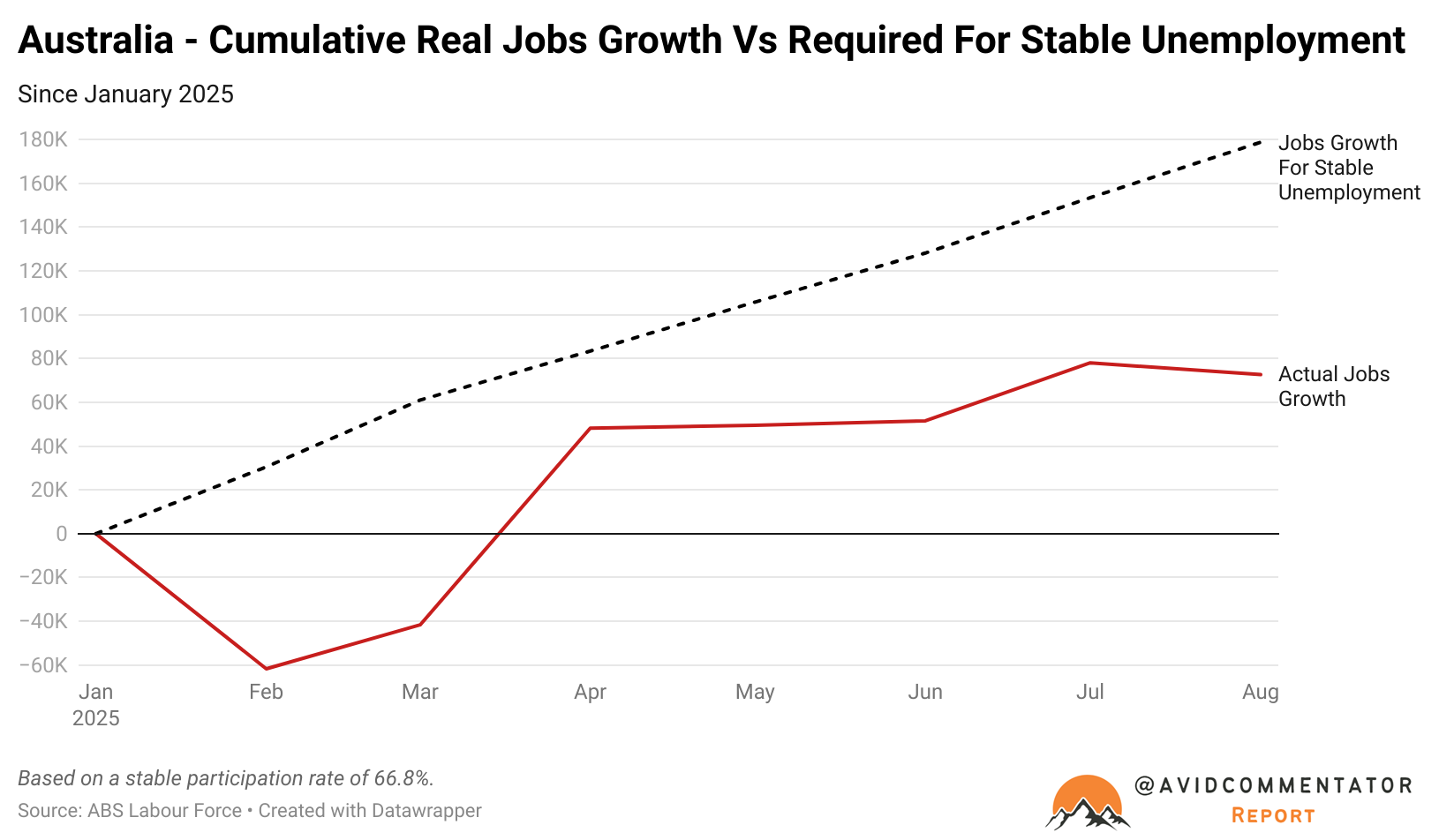

With the economy not producing enough jobs to keep up with the growth in the size of the labour force, assuming a stable participation rate, unemployment appears set to rise unless job growth can refire in the coming months.

This would leave the RBA in a challenging position; in a matter of potentially just a few quarters, unemployment could be rising to a level significantly higher than its long-term forecasts and inflation could still be simmering at a deeply uncomfortable level.

At that point, what do Michele Bullock and the RBA do?

Do they let inflation run hotter than the RBA would like in order to cut rates in an attempt to protect the labour market?

Or do they keep rates roughly where they are to contain inflation and leave the issues of a deteriorating labour market to fiscal policymakers?

One suspects that if the labour market deteriorates badly enough, the RBA will be left with little choice but to cut rates, regardless of issues with simmering inflation.

But the big question is where would that line be drawn? How high would the nation’s jobless rate have to rise before the pressure, both internally and externally, was enough to force their hand?

In a scenario in which the labour market fails to produce enough jobs to keep up with working-age population growth, this question could come to define the short- to medium-term future of the Australian economy.