While Japan welcomes almost 37 million visitors per year and is widely considered one of the safest places in the world, in quarters more focused on economics, the focus is often placed on its status as a cautionary tale.

In some ways, this characterisation is entirely fair. Japan is the developed world’s poster child for engaging in a debt-driven economic boom, which pumped asset prices into the stratosphere, only for it to all collapse into a lost decade.

It would take almost three and a half decades for Japan’s main stock index, the Nikkei, to recover back to where it was in late 1989.

Meanwhile, in Japan’s housing market, in 1989, the value of the land on which the Imperial Palace sat in Tokyo was greater than all the real estate in the U.S. state of California combined.

Yet despite the collapse of Japan’s massive debt bubble, there was something of a silver lining. They were left with the expansive and high-quality infrastructure network built up over the boom years, enormous levels of industrial capacity and a highly cohesive society.

The Last Decade Vs the Lost Decade?

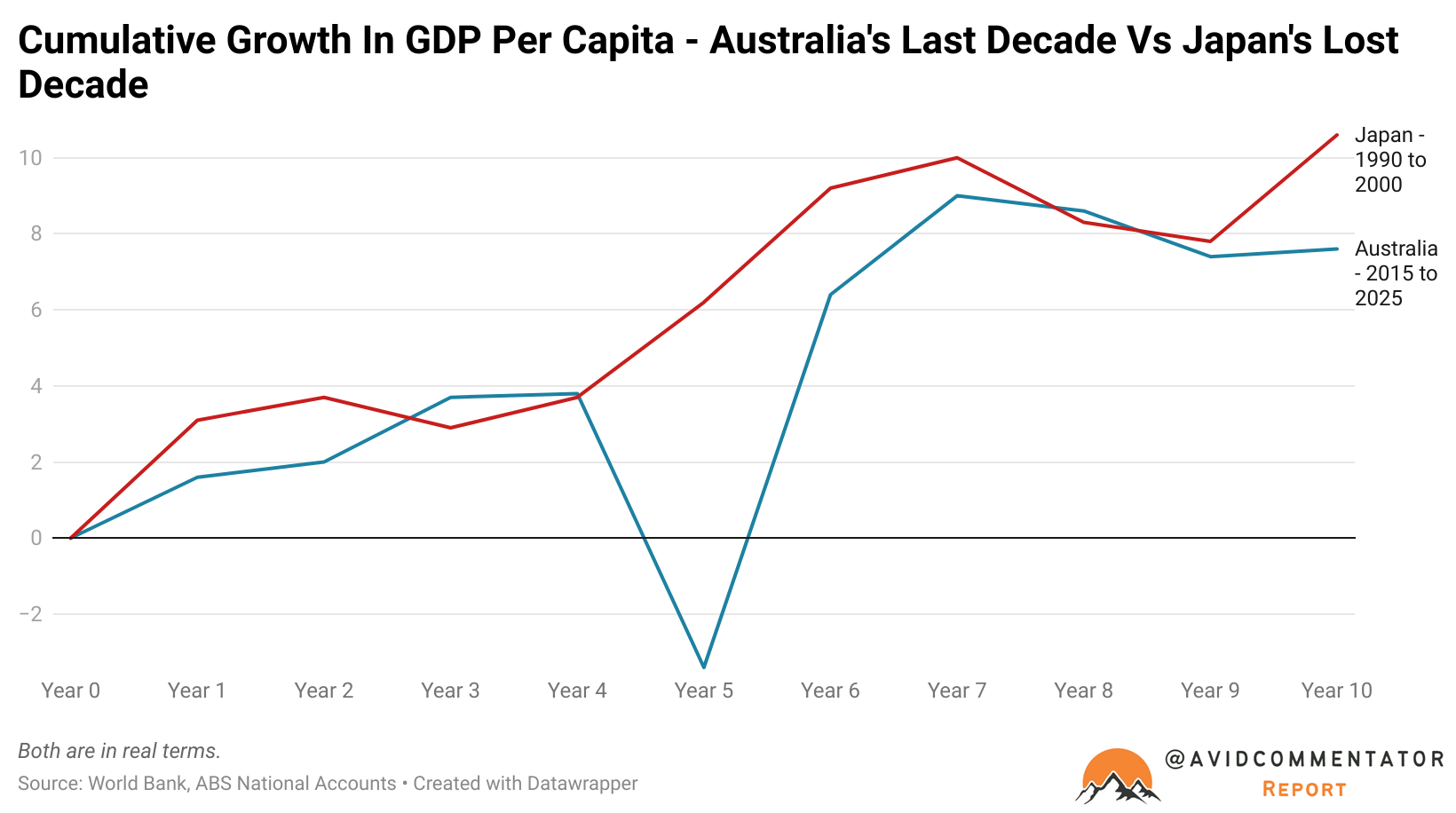

It’s here that we take a step back and contrast Japan’s dreaded ‘Lost Decade’ with the Australian economy’s performance over the last decade in terms of GDP growth per capita.

For Japan, our journey begins in 1990, which saw the asset bubble swiftly begin to unwind.

Between December 1989 and December 1990, the Nikkei index shed almost 40% of its value. By September 1992, it had lost over 60% of its value.

Yet despite these deeply challenging conditions and multiple years of flat-out economic contraction seen during the Lost Decade era, at the end of that decade, Japan’s cumulative GDP per capita growth was greater than Australia’s has been over the last decade.

The Takeaway

It’s certainly true that Japan faces a long list of different issues, including demographic decline, the highest level of government debt in the developed world and rising global trade barriers.

Australia is following Japan down many of the same challenging paths, despite having Japan as a cautionary tale about issues that are best avoided.

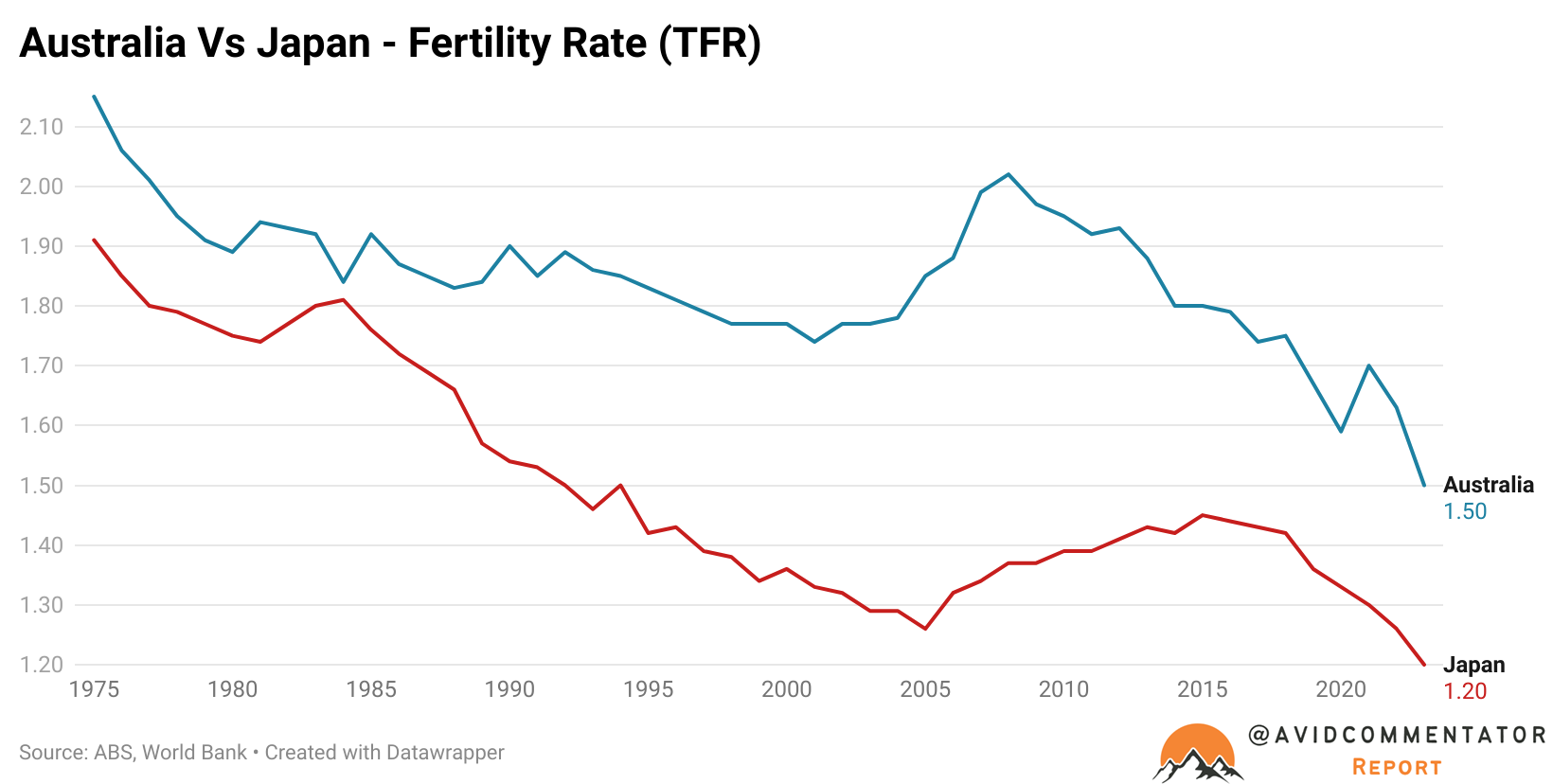

Australia’s fertility rate today is not dramatically removed from where Japan’s was in the late 2010s.

Meanwhile, Australia’s vice is not central government debt, it is household debt. And we also face growing issues with debt at a state level.

On the avenue of trade, Australia is heavily desensitised to the direct impact of a potential downturn in the global manufacturing cycle.

But it is arguably more exposed than most through its strong economic ties to China, which is running the largest manufacturing trade surplus as a percentage of global GDP in the history of the world.

Japan walked away from its boom a cohesive and safe nation, able to enjoy the fruits of the massive infrastructure construction push to this day and beyond.

Regardless of the timing of the next economic cycle, Australia faces a distinct challenge: a significant structural infrastructure deficit, a society increasingly divided on the general benefits of migration, and a legacy of debt that will burden the nation’s households and the broader economy for years to come.