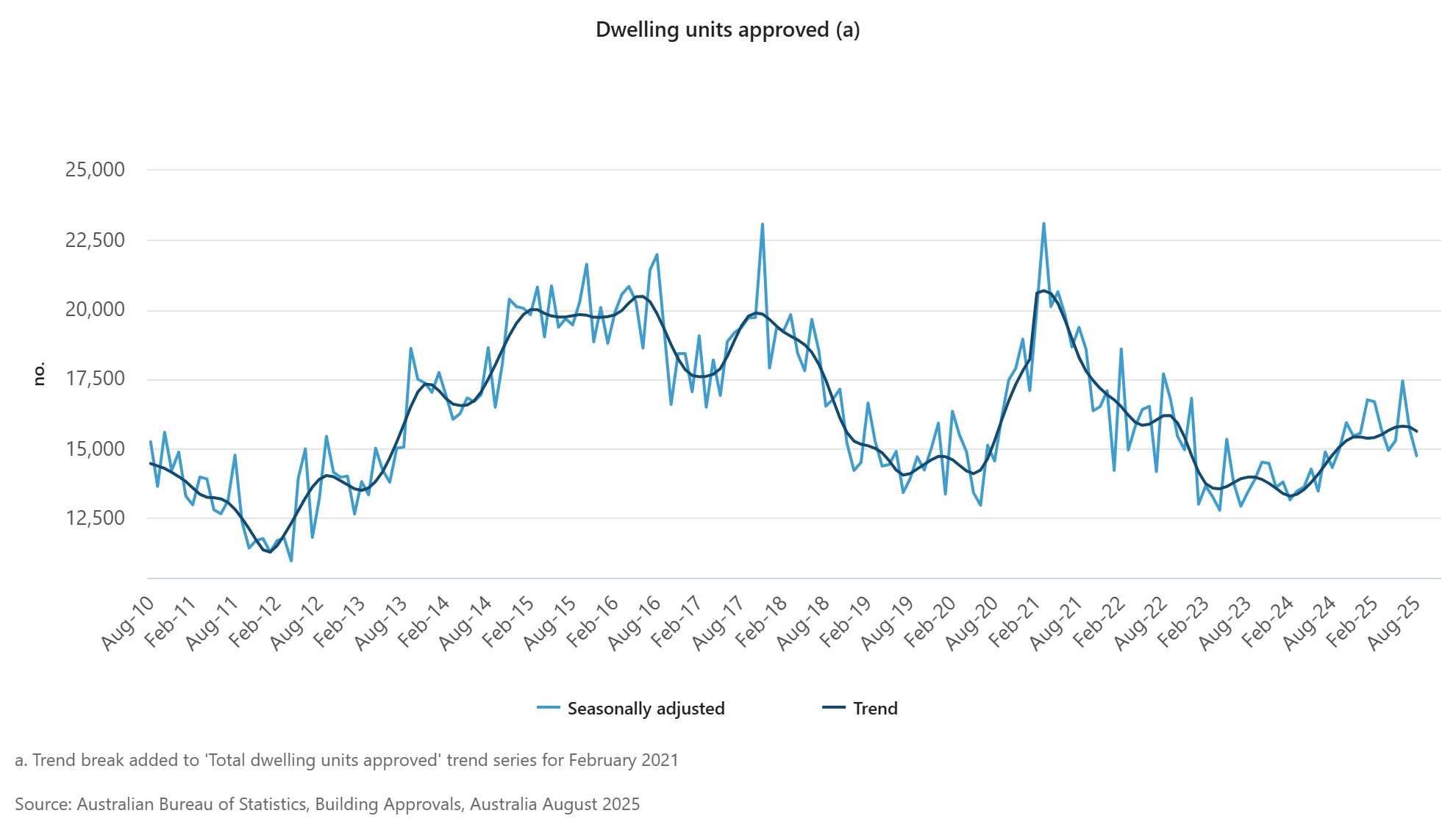

With the release of the latest ABS Building Approvals data for August, it was revealed that dwelling approvals had fallen by 6.0% on a month-on-month basis but were still up 3.0% year-on-year.

However, looking at a chart of trend approvals shows they had rolled over recently. This provides a concerning sign that there may not be much room for growth in the current homebuilding cycle without an external positive catalyst.

There was already a broad consensus that the Albanese government would come up well short of its target of building 1.2 million homes over the 5 years from June 2024 onwards. But this recent data is a concerning sign that home construction may end up so weak relative to population growth that the nation’s housing shortage may persist to at least the mid-2030s.

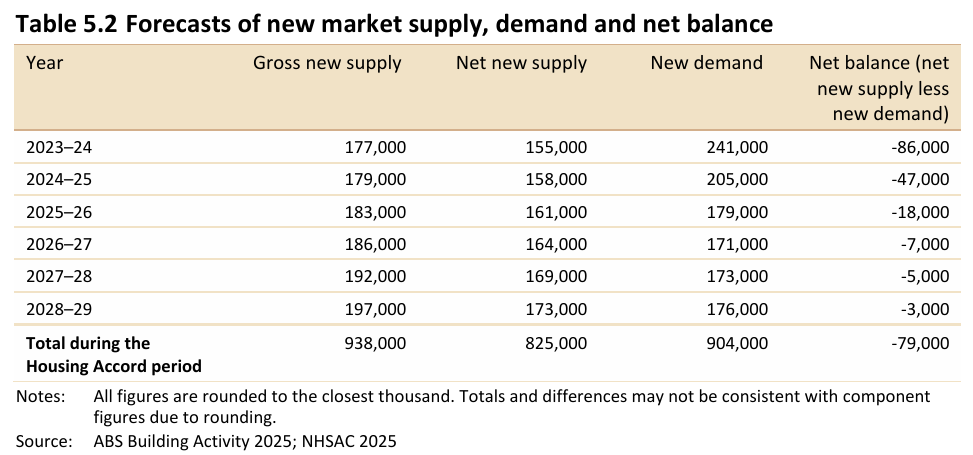

As things currently stand, the expectation from the Albanese government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council is that housing demand growth will outstrip housing supply growth until at least mid-2029.

It’s worth noting that this is based on the migration forecasts from the Centre for Population being realised and the nation not seeing yet another surprise to the upside in net overseas migration, as has become common in the last 3 years.

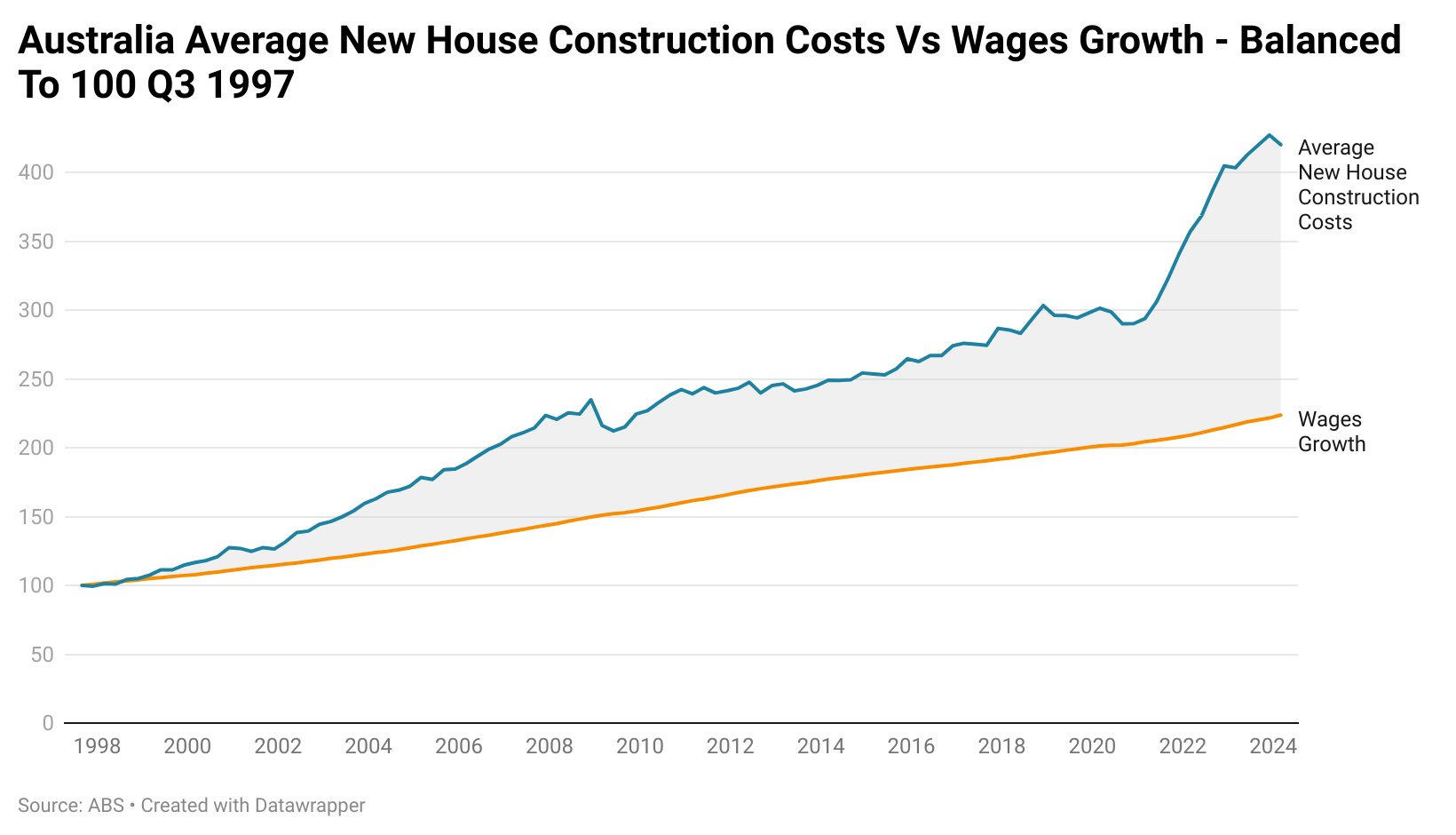

The issue primarily stems from the escalating cost of new home construction compared to income levels.

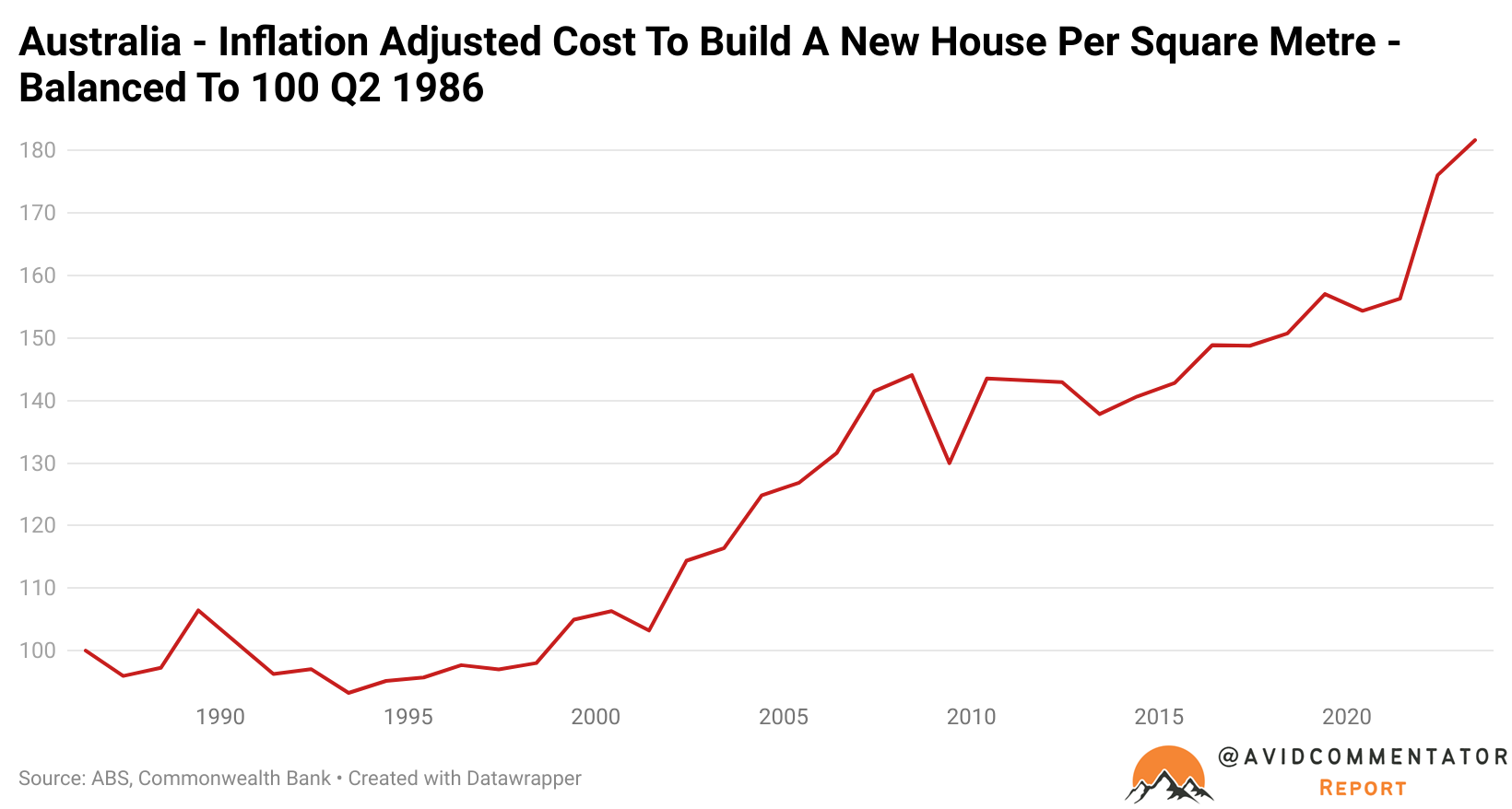

It’s also not just an issue of larger houses, as some have suggested. The cost of building a new house per square metre in inflation-adjusted terms has rocketed since the early 2000s. I previously covered this in much greater detail in a long-form article at Burnout Economics.

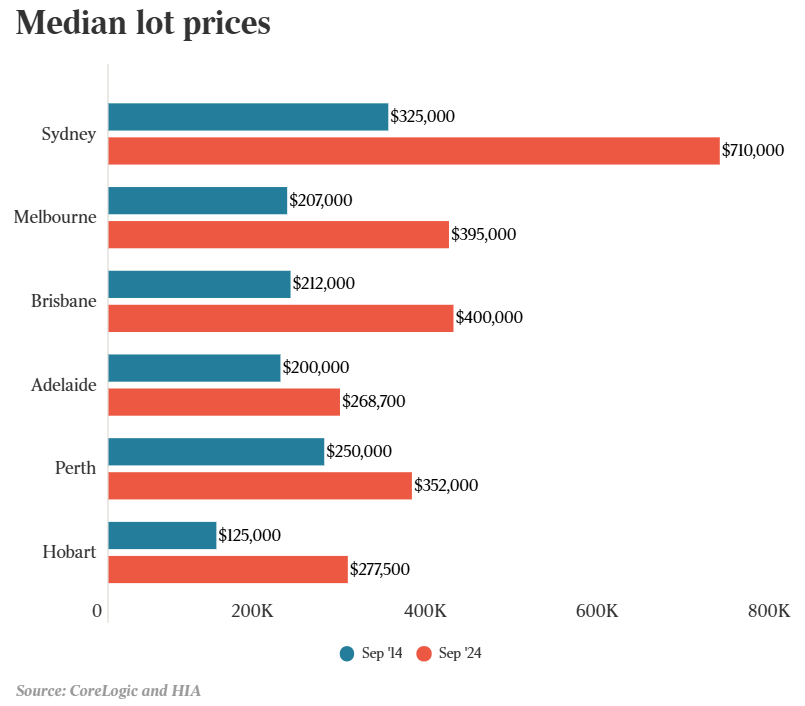

On the other side of the new home building cost equation, the cost of land has also skyrocketed across the nation’s major cities, despite the size of new home blocks decreasing dramatically.

The Takeaway

Australia is in the grips of a perfect storm when it comes to housing.

On one hand, new homes are increasingly expensive to build relative to incomes and rate cuts are increasingly priced in to be far more limited than anticipated.

On the other hand, housing demand is expected to persist at a level greater than supply growth even if the Centre for Population’s immigration forecasts are realised.

When the Albanese government first proposed its goal of building 1 million homes in five years and later revised it to 1.2 million homes, it was put out there as an aspiration.

In reality, one million new homes in the next five years would not end the nation’s housing shortage, as estimated by AMP.

Even 1.2 million new homes wouldn’t be enough if the underlying population growth assumptions remain the same as laid out in the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council’s report.

It’s a deeply challenging set of circumstances, where there are some easy and obvious answers. However, they are not politically desirable for the Albanese government at this point.