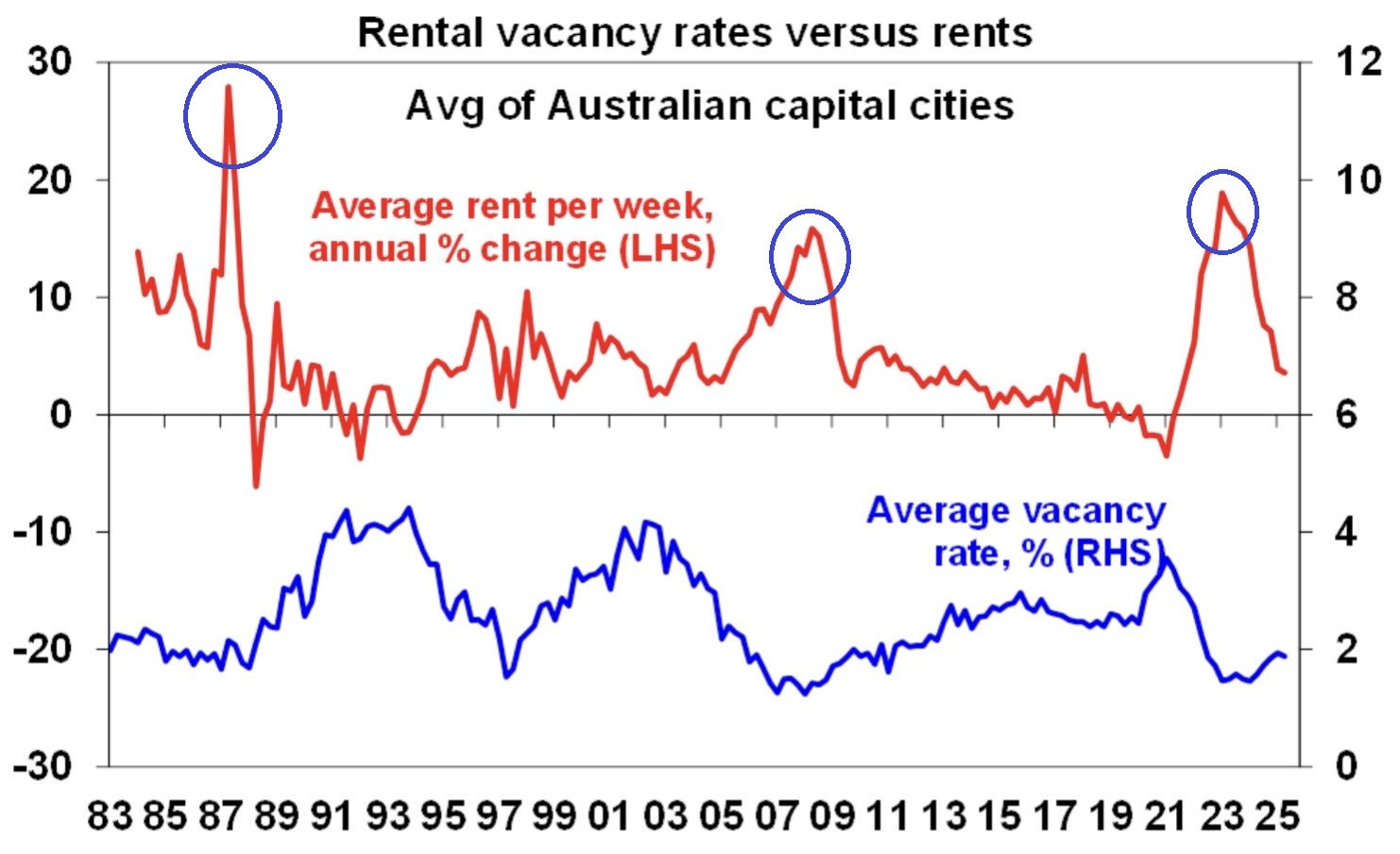

Recently, AMP Chief Economist Shane Oliver posted the chart below on Twitter (also known as X) detailing the path of rental vacancy rates and asking rents since the early 1980s.

As I have somewhat crudely illustrated in the chart below, with the three blue circles, there have been three major surges in asking rents over the last 40 years: the mid-1980s, the run-up to the Global Financial Crisis, and immediately after the pandemic.

Before getting into the numbers, it’s worth noting that part of the reason for the very different peaks in growth in asking rents is down to differing rates of wage growth and inflation during the various eras.

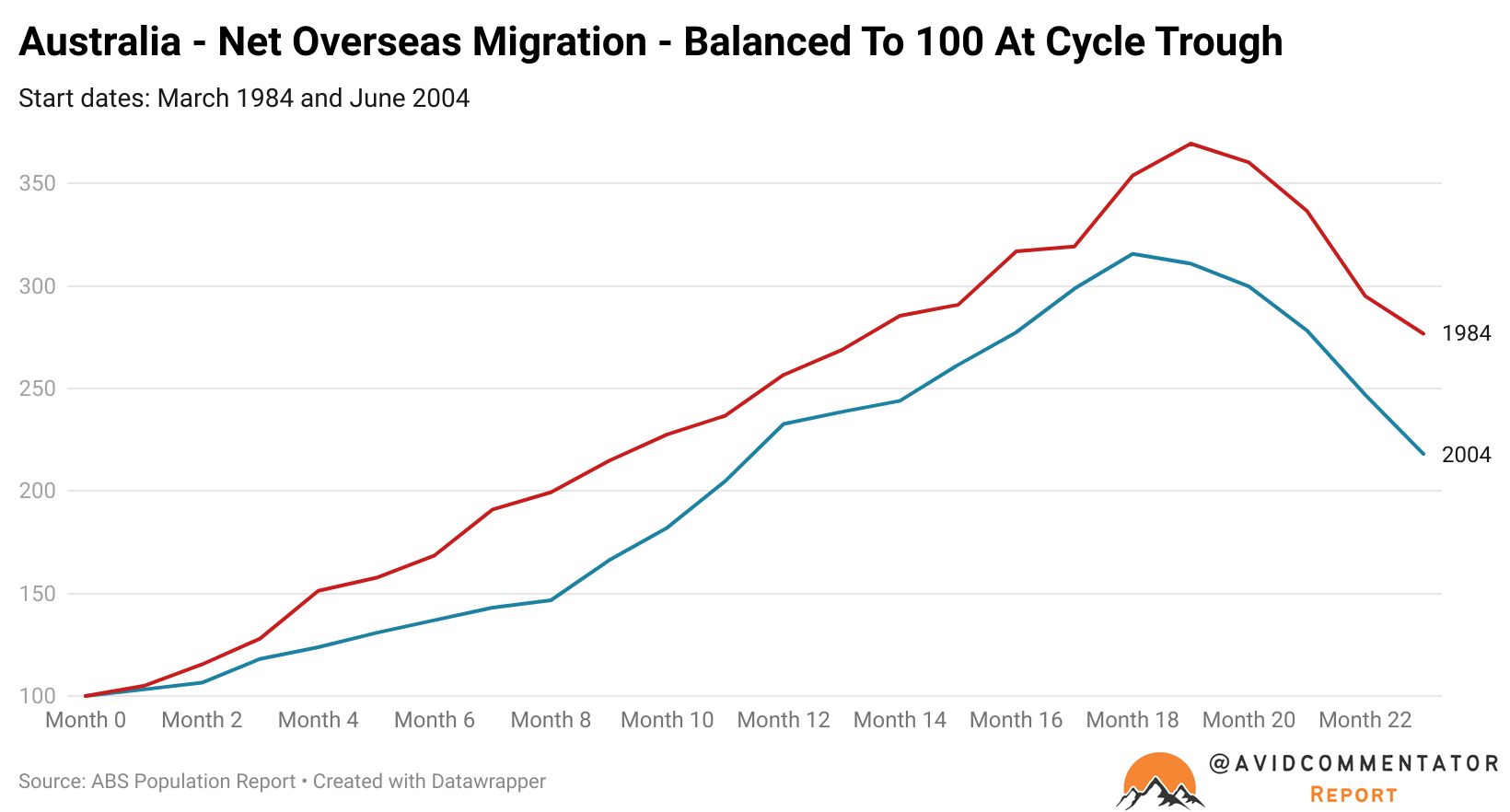

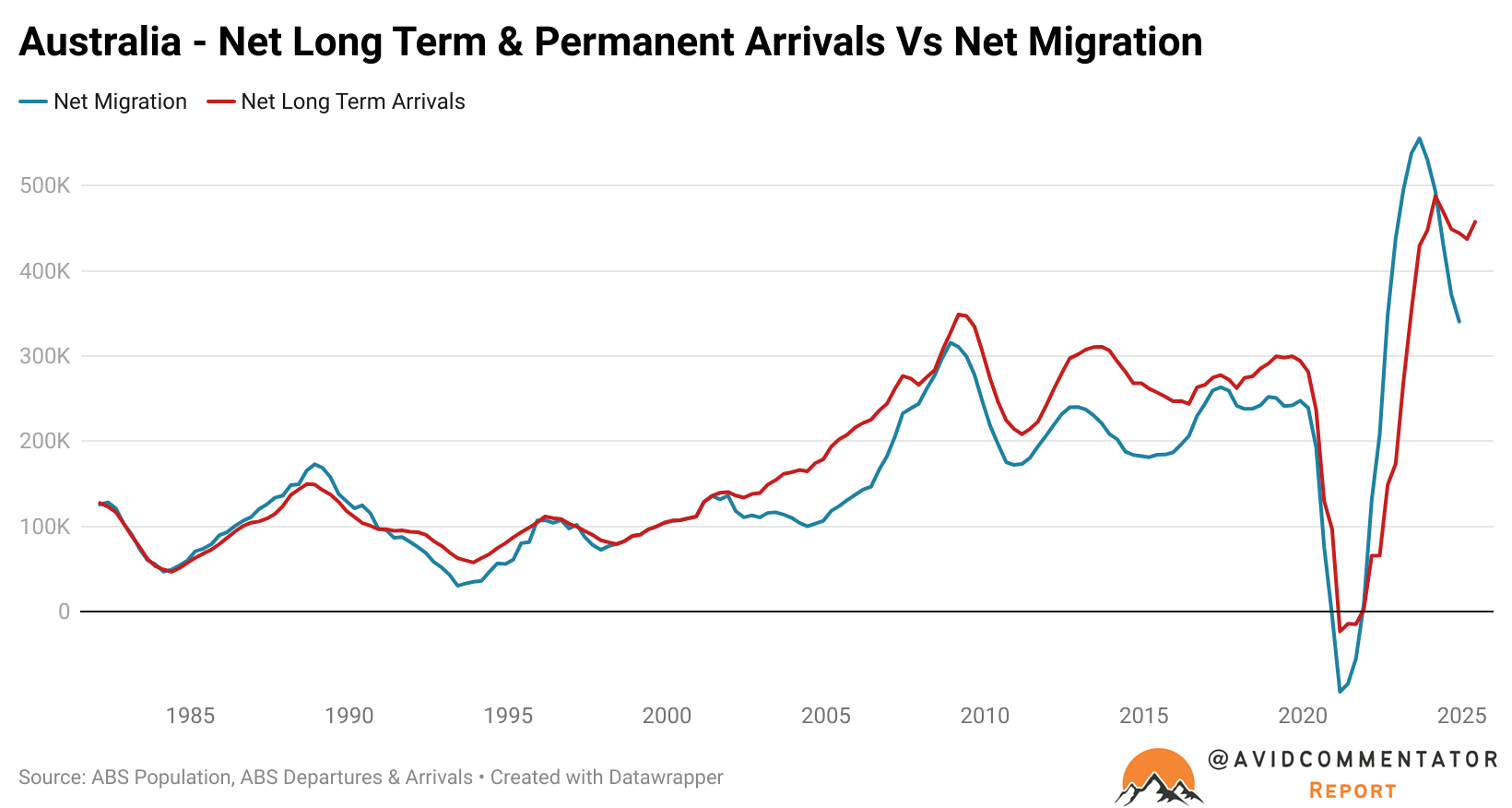

Looking at the relative performance of net overseas migration prior to and during the first two surges in asking rents on AMP’s charts, the correlation between the two is swiftly clear.

During the mid-1980s cycle, annual net overseas migration went from 46,800 in March 1984 to a peak of 172,900 in December 1988, a relative rise of 269.4%.

During the mid-2000’s cycle, annual net overseas migration went from 100,000 in June 2004 to a peak of 315,700 in December 2008, a relative rise of 215.7%.

Given the outsized rises in migration, it’s unsurprising that this additional housing demand resulted in such significant surges in asking rents.

Unfortunately, due to the fact that statistics during the pandemic produced very low and even negative numbers for the annual rate of net overseas migration, the current cycle can’t be measured in the same way as the previous two.

In the final quarter unaffected by the pandemic, Australia recorded an annual net overseas migration figure of 247,600 people.

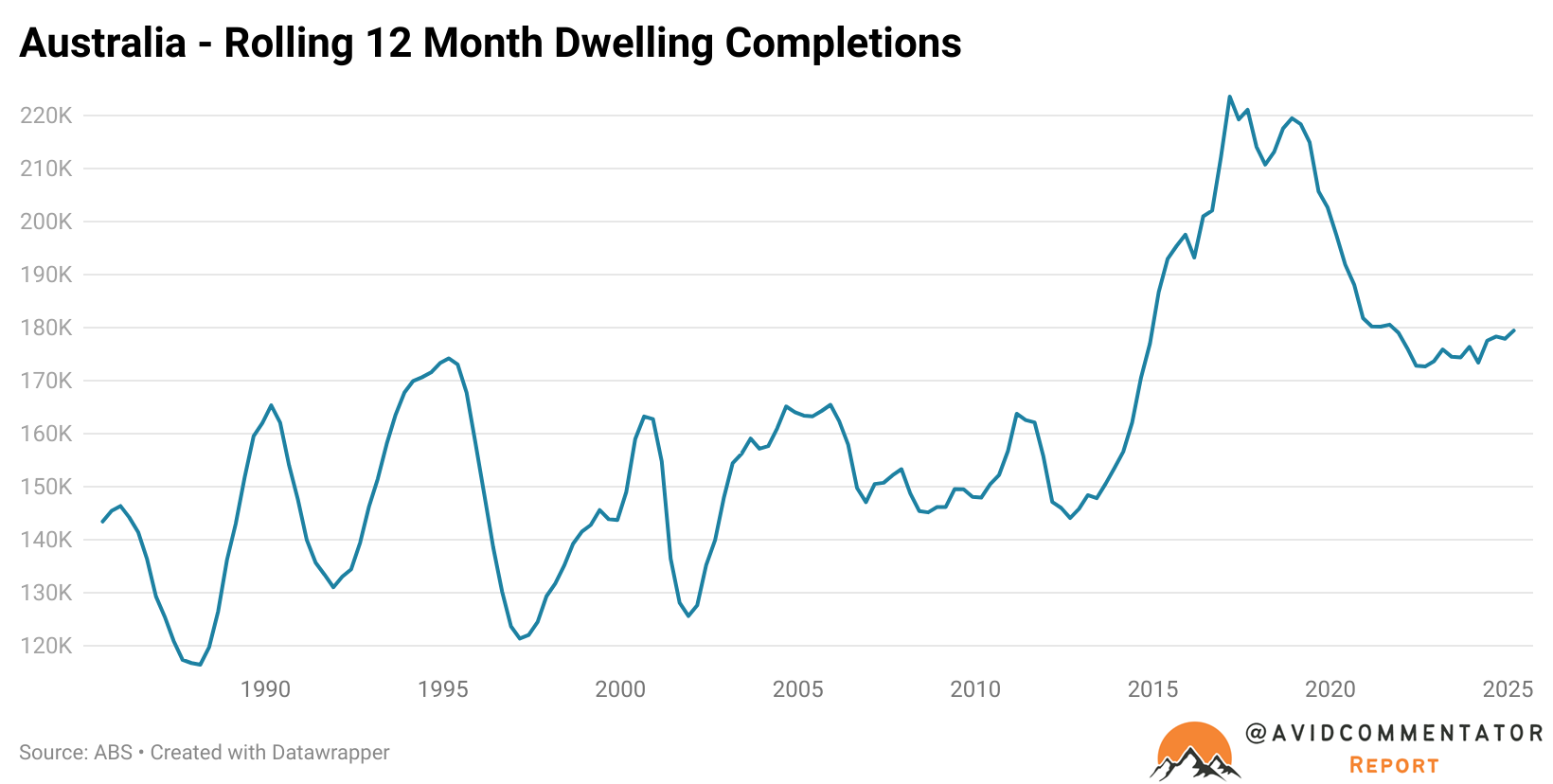

At this point, a robust dwelling completion cycle was still contributing to keeping growth in asking rents under control.

Since then, dwelling completions have fallen significantly, and most industry experts and economists do not forecast a return to pre-Covid peaks in their forward estimates.

According to the latest data from the ABS, which covers up to the end of the March quarter of 2025, annual net migration is currently 316,000.

While this is down significantly from the peak of 555,800 in the September quarter of 2003, it’s still 37.6% higher than the final pre-pandemic reading.

However, the damage has already occurred.

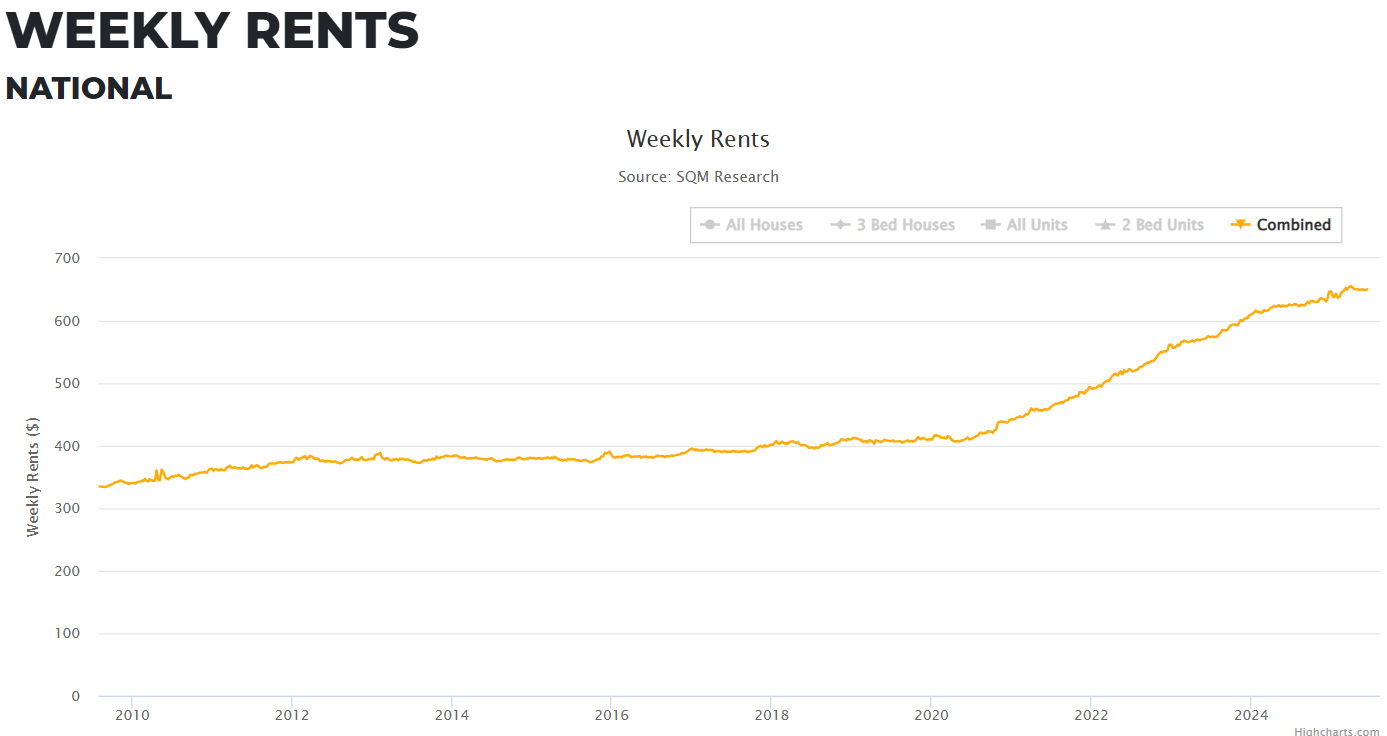

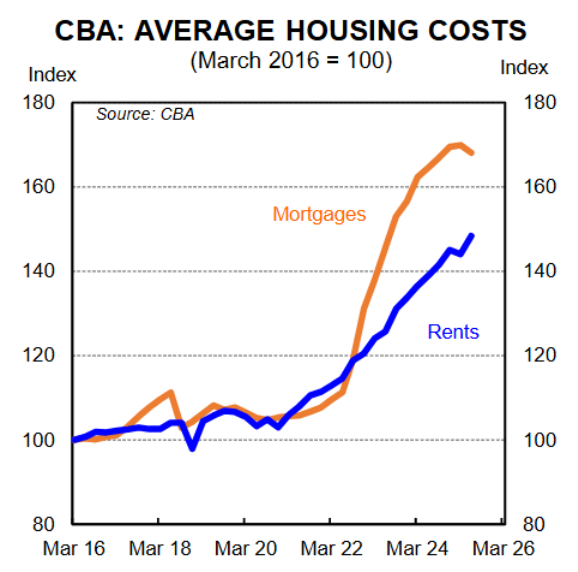

According to data from SQM Research, asking rents are up by more than 50% at a national level compared with their pre-pandemic peak and average payable rents are up by approximately 45%, according to data from the Commonwealth Bank.

The Takeaway

While there are arguments to be made that the periods prior to the three historic major surges in rents held a relative degree of rental affordability for their respective eras, the surge in the migration intake associated with all three helped to provide landlords with the market leverage to pursue outsized increases in rents.

Given the negative impact on household formation for younger demographics that resulted from the surge in rents in the mid- to late 2000s, one would imagine that the government would want to be deeply careful of pursuing a migration intake that could once again get so far ahead of housing supply.

Alas, that has unfortunately not been the case, with the Albanese government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council reporting that the housing shortage will likely persist into the next decade.