Recession warning light flashes for Aussie economy

As the Australian economy progresses, increasingly driven by the expanding size of government and the rising population, warning lights are beginning to signal that not everything is well.

Like a real car, it’s possible that the warning lights are being thrown up due to a faulty sensor, in this instance, the deterioration of multiple labour market indicators.

When there was one indicator, the labour force account pointing to the weakening state of employment growth, it was a significant concern.

A few weeks ago, I highlighted this deterioration in an article on Burnout Economics.com.

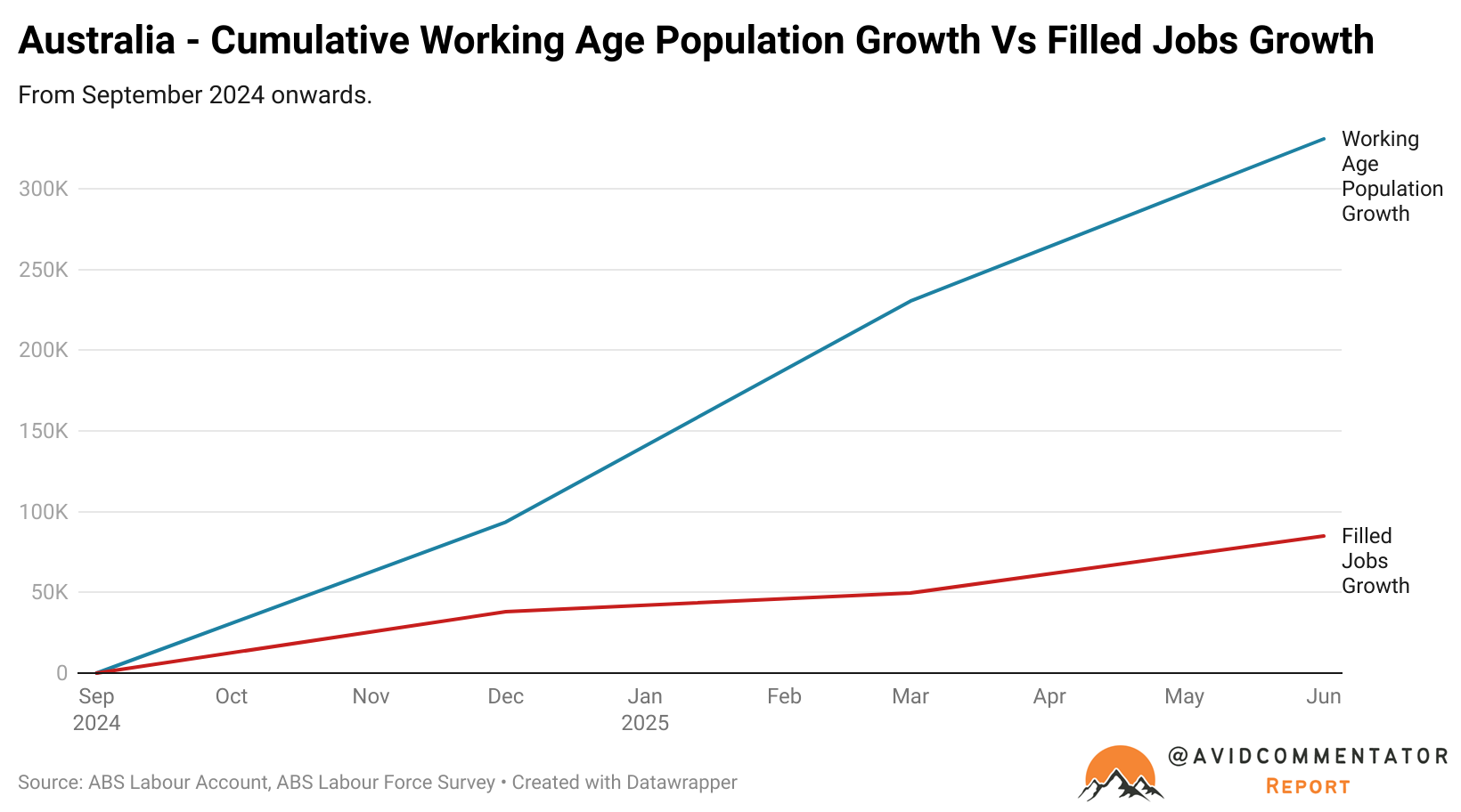

The latest ABS Labour Account data provided further fuel for concern, revealing that just 35,300 jobs were created in the June quarter.

This marks the third straight quarter of weak jobs growth, at least relative to the still highly elevated rate of working age population growth, with just 11,500 jobs created in the March quarter and 38,000 jobs in the December quarter of last year.

Across the last three quarters of data combined a total of 85,000 jobs were created in net terms, while the working age population has expanded by over 337,000.

Then with the release of the August Labour Force data, the warning lights on the dash began to further multiply.

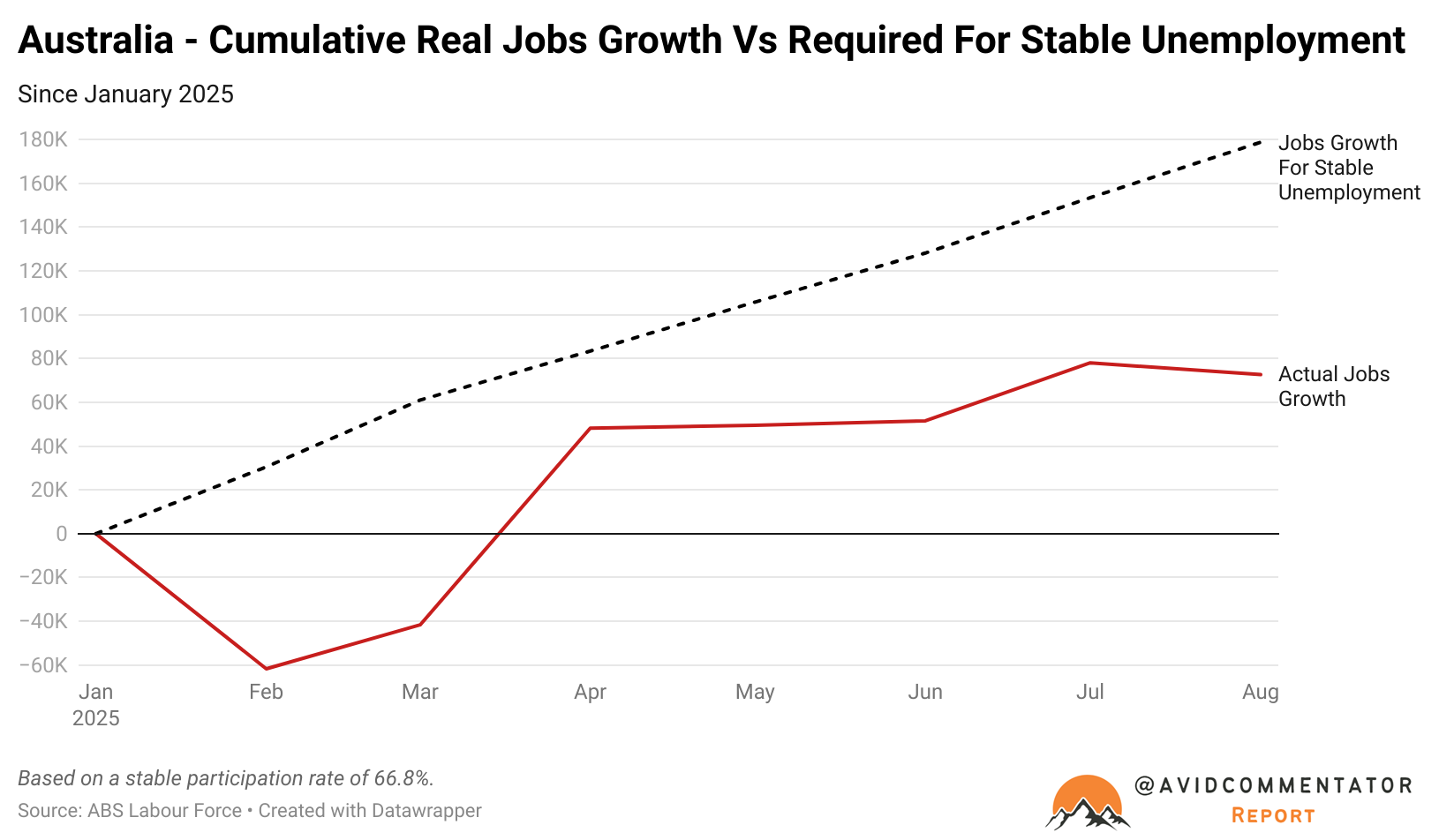

For the month of August, 5,400 jobs were lost, with 40,900 full-time positions shed and 35,500 part-time positions gained.

While this was an extremely poor result, particularly when put into context with the still extremely high rate of working-age population growth, a rise in unemployment to around 4.44% was prevented by a fall in the participation rate.

Zooming out and taking a longer view of the data, the economy has created just 72,600 jobs since January, with 40,500 being of the full-time variety.

While 72,600 jobs created in 7 months is not an awful number in a vacuum, when put into context with the working-age population expanding by 267,500 across the same time, it swiftly becomes clear the challenge the Australian labour market faces.

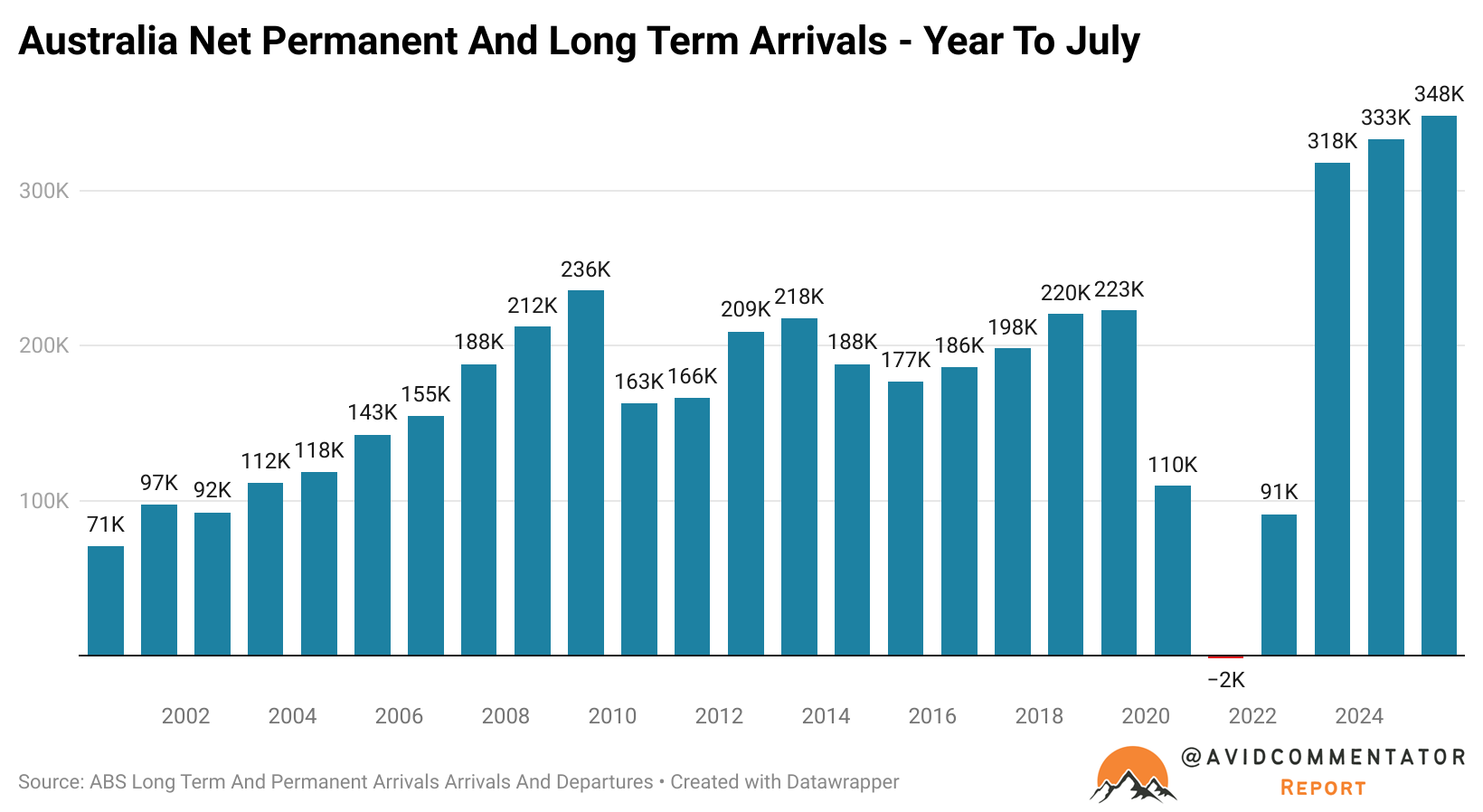

With net long-term and permanent arrivals pointing to a migration intake that will likely remain above pre-Covid norms, the labour market needs to produce robust jobs growth just for the unemployment rate to stand still.

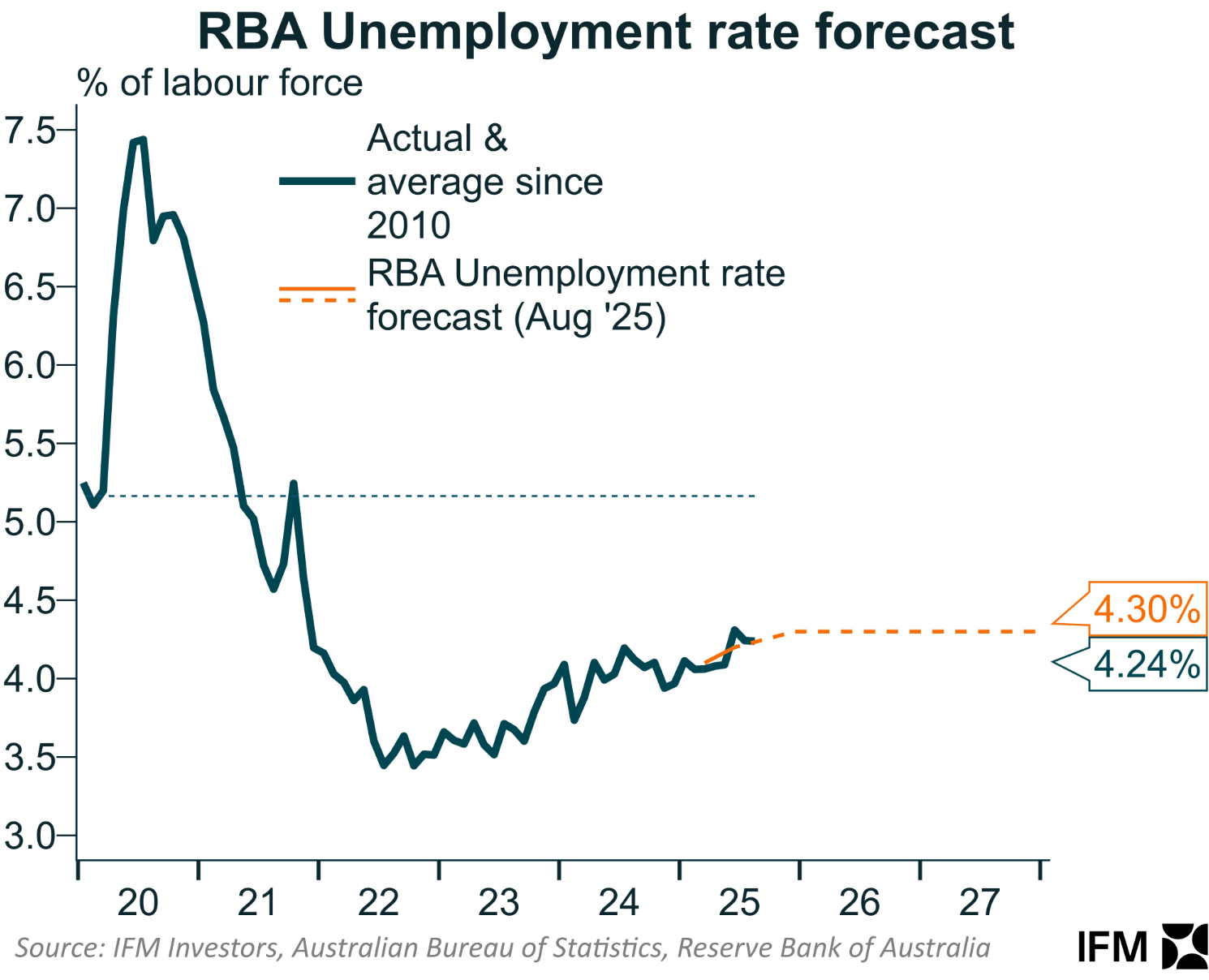

If labour market conditions continue to deteriorate or even remain roughly where they have been since the start of the year, it’s only a matter of time before the RBA’s unemployment forecast of 4.3% is exceeded significantly, with unemployment just 0.06 percentage points away from that figure today.

Chart: Alex Joiner IFM Investors

Should that scenario materialise, the primary concern would be the impact on household confidence levels.

Currently the RBA and the nation’s businesses are pinning their hopes on increased spending supporting the economy and, by extension, private sector jobs growth.

Whether or not those hopes are realised in the next 12 to 18 months will play a defining role in the longer-term future of the nation’s economy, as will the response of the Albanese government.