Japan’s economy smokes Australia’s

Many often invoke Japan as a cautionary tale in discussions about Australia’s future and the appropriate level of migration, emphasising the importance of avoiding its fate.

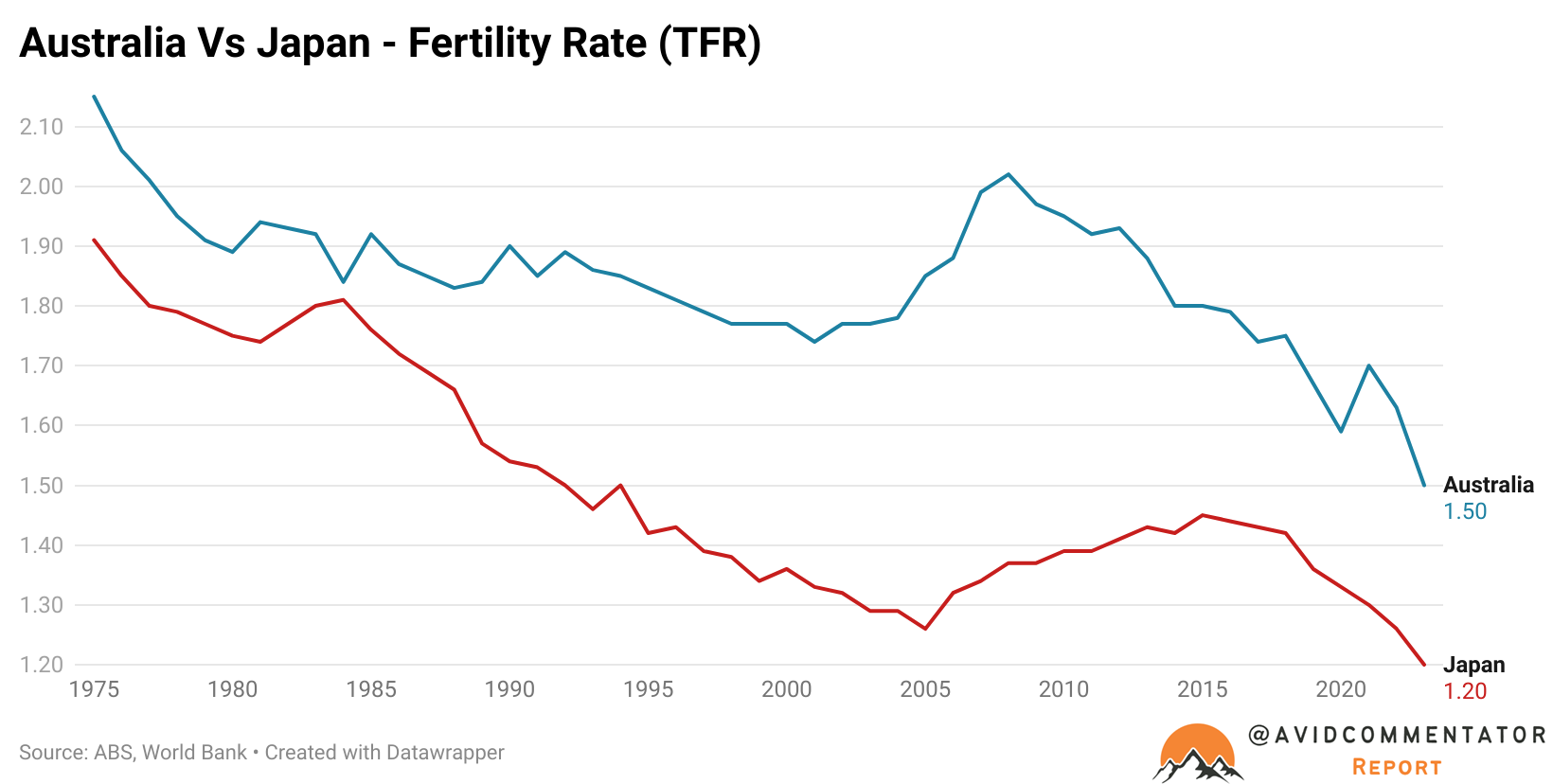

Viewed purely through the lens of fertility rates, that is undoubtedly the case; Japan has had a below-replacement fertility rate for over 50 years and, at a national level, has not done nearly enough to ensure the required social and economic changes to arrest that fall adequately.

That being said, Australia’s fertility rate today is only fractionally higher than Japan’s was in 2015, with 1.50 children per woman for Australia in the latest data versus 1.45 for Japan in 2015.

Beyond that rather obvious quantifiable issue, is Japan’s economy really so bad? Are we really doing so much better in Australia that we can consider ourselves superior?

The Headlines

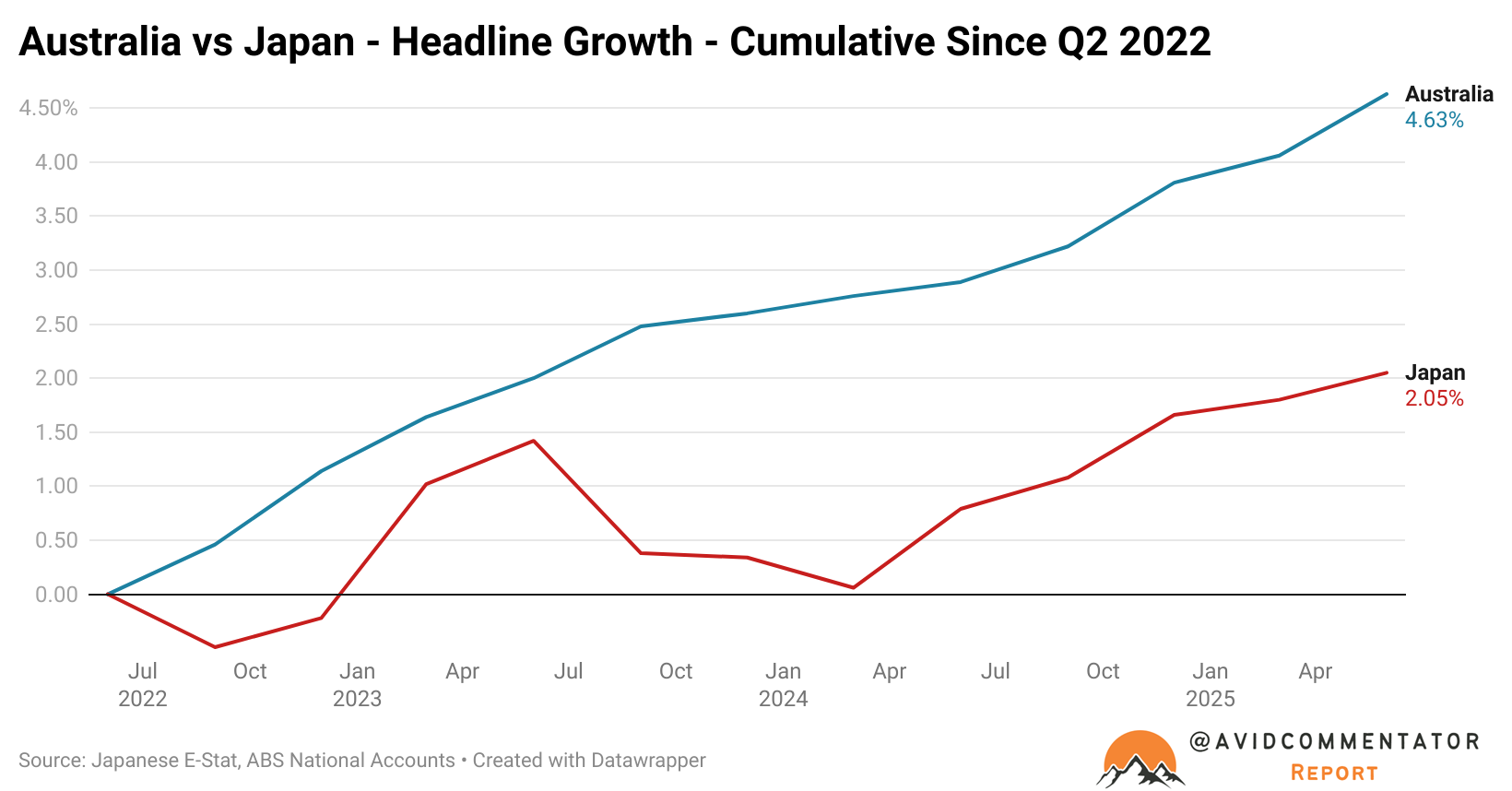

If we look at things purely in headline terms, then it’s certainly true that Australia is outperforming Japan.

For today’s purposes, we will be using Q2 2022 as our baseline, given that this is essentially when the support of stimulus and pandemic revenge spending in the two respective economies began to peak.

Since then, the Australian economy has grown by 4.63%, and the Japanese economy has grown by 2.05%.

The Reality In The Street

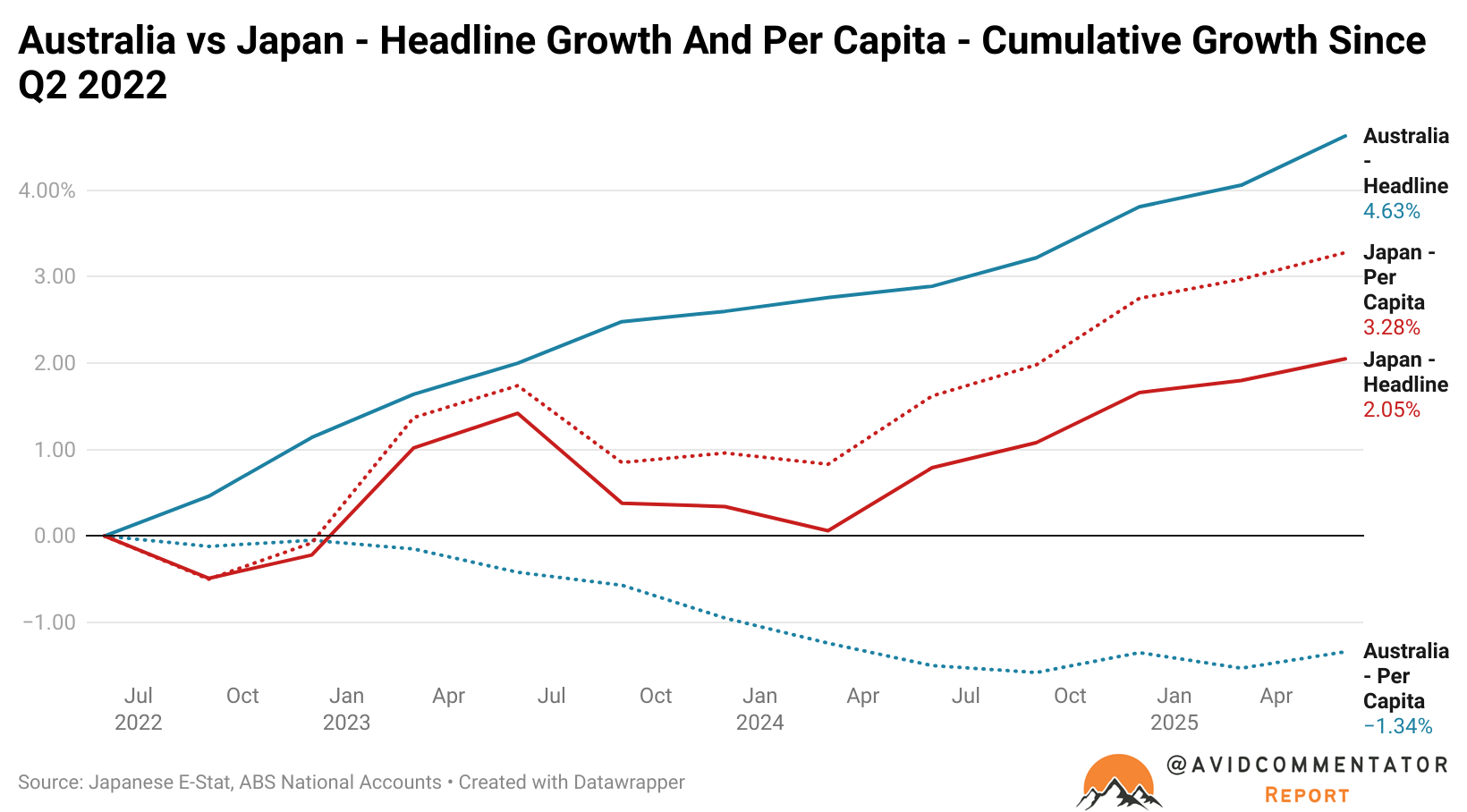

As you might expect, the reality of that growth for the average person in the street is not so simple.

Over the same time, Australia’s GDP per capita has contracted by 1.34%, while Japan’s has expanded by 3.28%, an outperformance for the average person in the streets of Japan of 4.62 percentage points.

In summary, Australia and Japan are pursuing two distinct economic strategies, with Japan being compelled by its circumstances, while Australia is doing so primarily by choice.

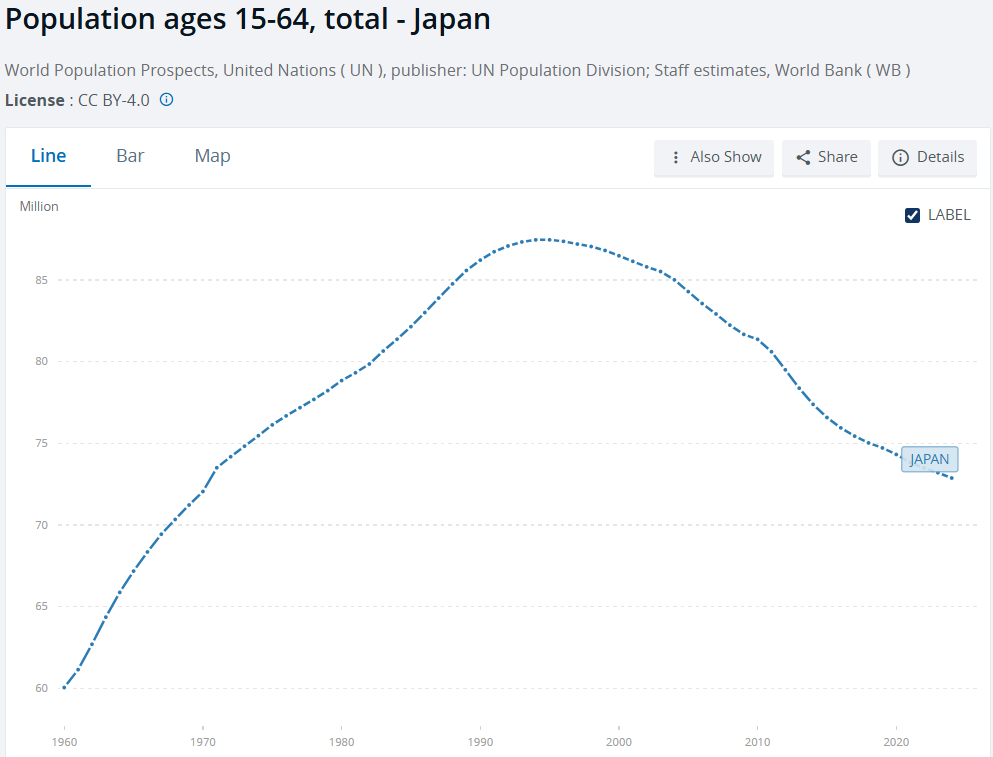

In Japan, the contracting population, and in particular the significant ongoing declines in the working-age population, have forced firms to more efficiently deploy the labour force Japan has, improving productivity.

The ongoing contraction in the population aged 15 to 64 should be putting the brakes on broader Japanese economic growth. Yet it isn’t, with the economy continuing to grow despite facing significant challenges in the form of a recession and inflationary pressures.

Meanwhile, Australia is effectively pursuing the complete opposite strategy; outsized levels of working-age population growth are boosting headline GDP but acting as a significant drag on productivity.

The Takeaway

While it’s certainly true that some aspects of Japan’s circumstances should be treated as a cautionary tale to be avoided, the unfortunate reality is that those are the parts of Japan’s path that Australia is inadvertently following, albeit for differing reasons.

Australia is doing the complete opposite of the parts of Japan’s economic strategy that are succeeding and delivering growth for its populace.

Instead of workers being redeployed in pursuit of the greatest possible productivity growth, Australia’s strategy of poorly targeted high migration and growth in the size and scope of taxpayer-funded employment has delivered anaemic productivity growth, despite some outstanding performances in some aspects of the economy, such as agriculture.

It is undoubtedly possible for Australia to follow a different path: one focused on productivity and growth driven by private enterprise. However, that would require some major changes to how the economy and our society operate.

And our political class isn’t ready for that, even if the electorate is.