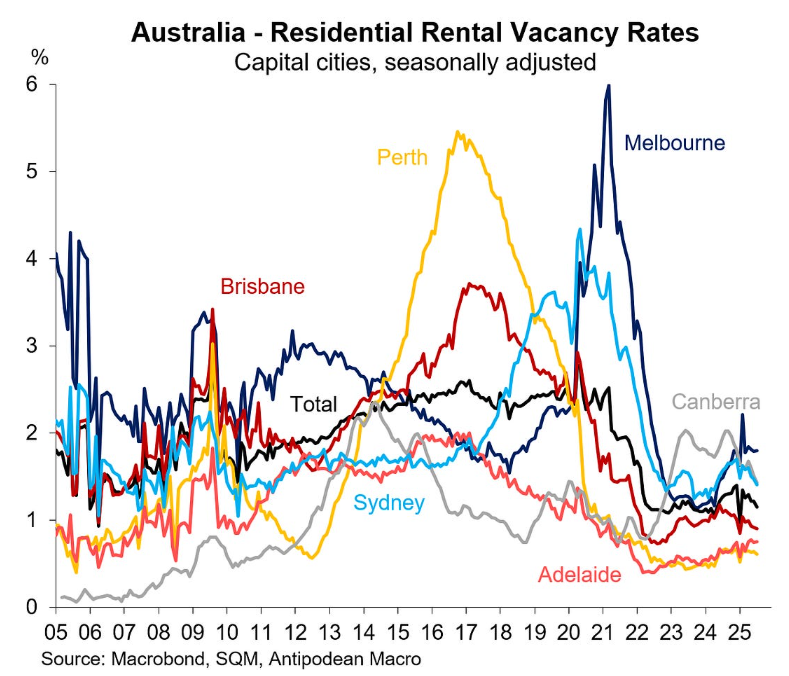

When Australia’s international borders reopened in early 2022, the nation was already well in the midst of a rental crisis.

As a result of the pandemic, demand for rentals surged significantly, first in regional areas as people sought to make their exodus from lockdown-impacted cities and then in the capitals as individuals stuck at home with family or in sharehouses sought to form their own households.

Chart: Antipodean Macro

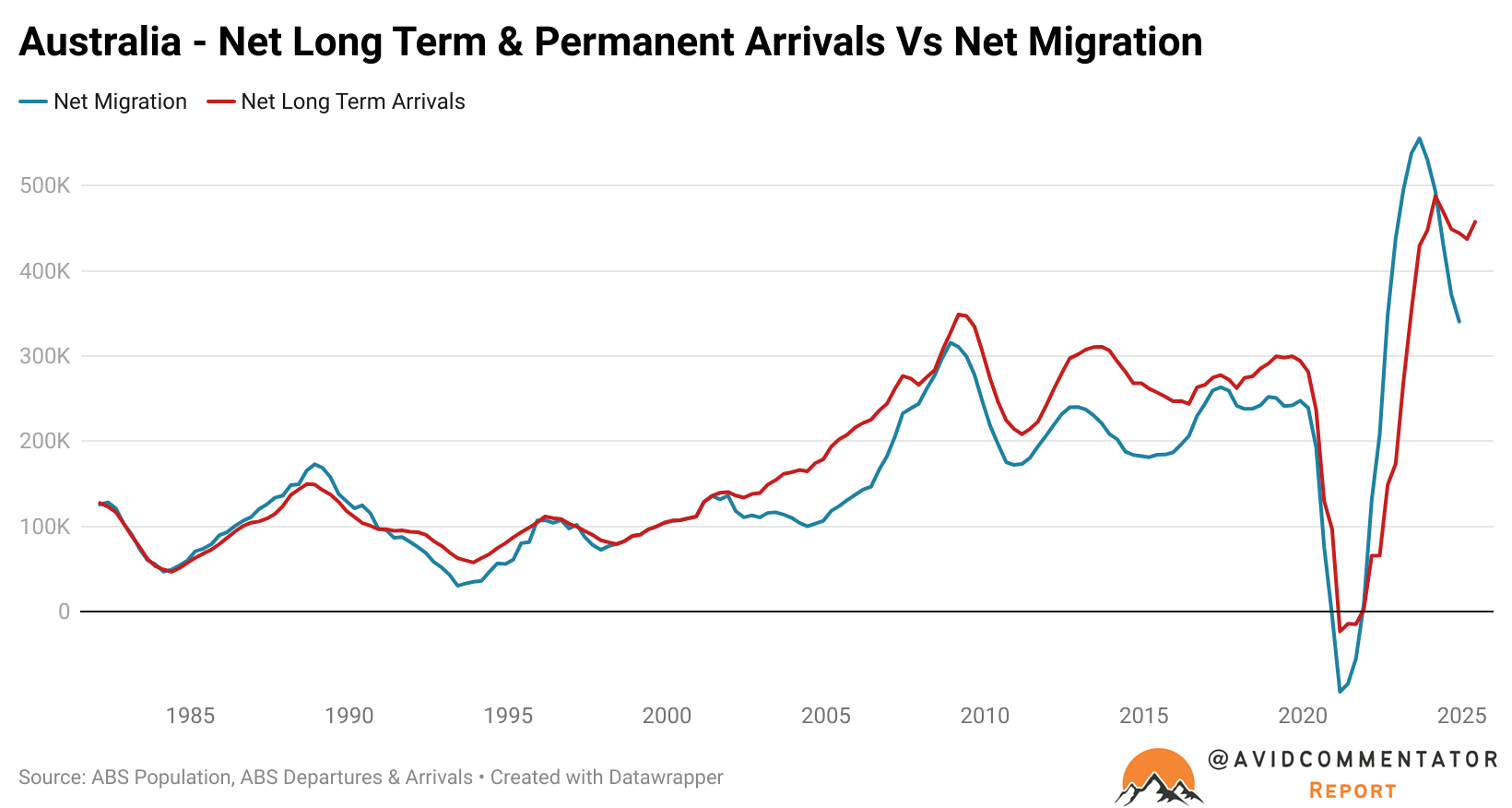

Then, as the international borders reopened in early 2022, the flow of migrants into the country was dramatically higher than expected.

In the words of the ABC’s Alan Kohler:

For the year ended June 2022, Treasury’s forecast was 41,000; it turned out to be 203,590.

For both 2022-23 and 2023-24, the forecast was 235,000; it turned out to be 535,520 and 445,640.

For 2024-25, the forecast was originally 260,000, and it then increased halfway through the year to 340,000.

In short, migration levels continued to surprise to the upside of Treasury and Centre for Population forecasts, placing significant stress on housing supply and exacerbating already challenging conditions in the nation’s rental market.

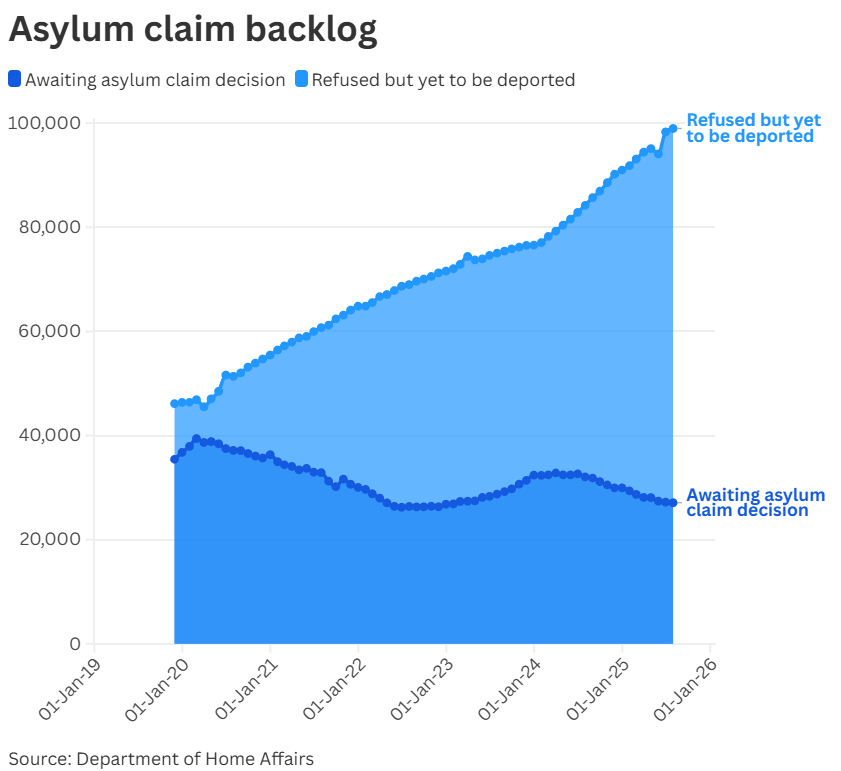

Meanwhile, News.com.au recently reported that:

International students are overwhelming Australia’s asylum system with bogus refugee applications, as the country’s deportation backlog surges towards 100,000.

As of July 31, there were 98,979 people whose protection visa application had been denied but were yet to be deported while 27,100 were awaiting a decision, according to the Department of Home Affairs.

Chart: News.com.au

Those 98,979 are currently on bridging visas and the overwhelming majority are out and about going about their business in the nation.

Dr Abul Rizvi, the former deputy secretary of the Immigration Department, estimates that there are roughly 50,000 who have exhausted the appeals process yet remain in the country unlawfully.

Yet despite the enormous growth in the number of failed asylum seekers, just 162 were deported during the 2024-25 financial year.

Based on the average household size at a national level, the nearly 100,000 failed asylum seekers currently occupy over 39,000 homes.

Meanwhile, more homes still are occupied by individuals who came to Australia on a student visa but have since dropped out of study to pursue a different visa to stay in the country.

According to Salvatore Babones, the Associate Professor Sociology and Criminology at the University of Sydney, there is a “emerging phenomenon” of increasing dropout rates as international students “recognise you can get in on a university visa and switch”.

“This is the new scam,”

“We have many universities, mostly regional, that have dropout rates of (more than) 50% after the first year.” Babones said

But despite the clear incentive provided by the abject failure of the government to deport failed asylum seekers who have exhausted their avenues of appeals, the issue continues to persist.

Dr Rizvi has concluded that issue of unlawful non-citizens remaining in the country has been ignored by successive federal governments because the cost of deporting them all “would be eye-watering”.

In the words of Dr Rizvi:

“Many ministers have asked that question, and the response they’re given is, ‘Yes, Minister, we can do that but you’re going to have to find us a huge amount of money.’ Most likely in the hundreds of millions, if not more,”

“You’re going to have to build huge numbers of detention centres, then there’s going to be a huge amount of legal costs as these people appeal their deportation decisions. Many of them will be difficult to deport even after that.

“Most governments, when confronted with those facts, have just said, ‘Let’s let it go through to the keeper.’” Rizvi said.

The Takeaway

If the Albanese government had the courage to confront the issue of failed asylum seekers head-on and much more carefully vet temporary visa applicants before they enter Australia, tens of thousands of homes could be freed up, improving the nation’s rental crisis.

While it may not be a panacea or a comprehensive solution to the crisis, considering its severity, it would offer a pathway for the government to initiate positive changes in the issue within a comparatively short timeframe.

One would think this would be particularly pressing given that the federal government’s own National Housing Supply and Affordability Council forecasts that rental market conditions will remain challenging out to the end of this decade.