Over the last 25 years, China has undergone an absolute meteoric rise as an industrial and economic power, inadvertently dragging Australia along for the ride.

At the turn of the new millennium, China possessed the sixth-largest economy in the world, sandwiched between Italy and France in the rankings and possessing an economy just one-quarter the size of Japan’s.

Today, China is the world’s second-largest economy by a huge margin, with an economy more than four times the size of third-place Germany’s.

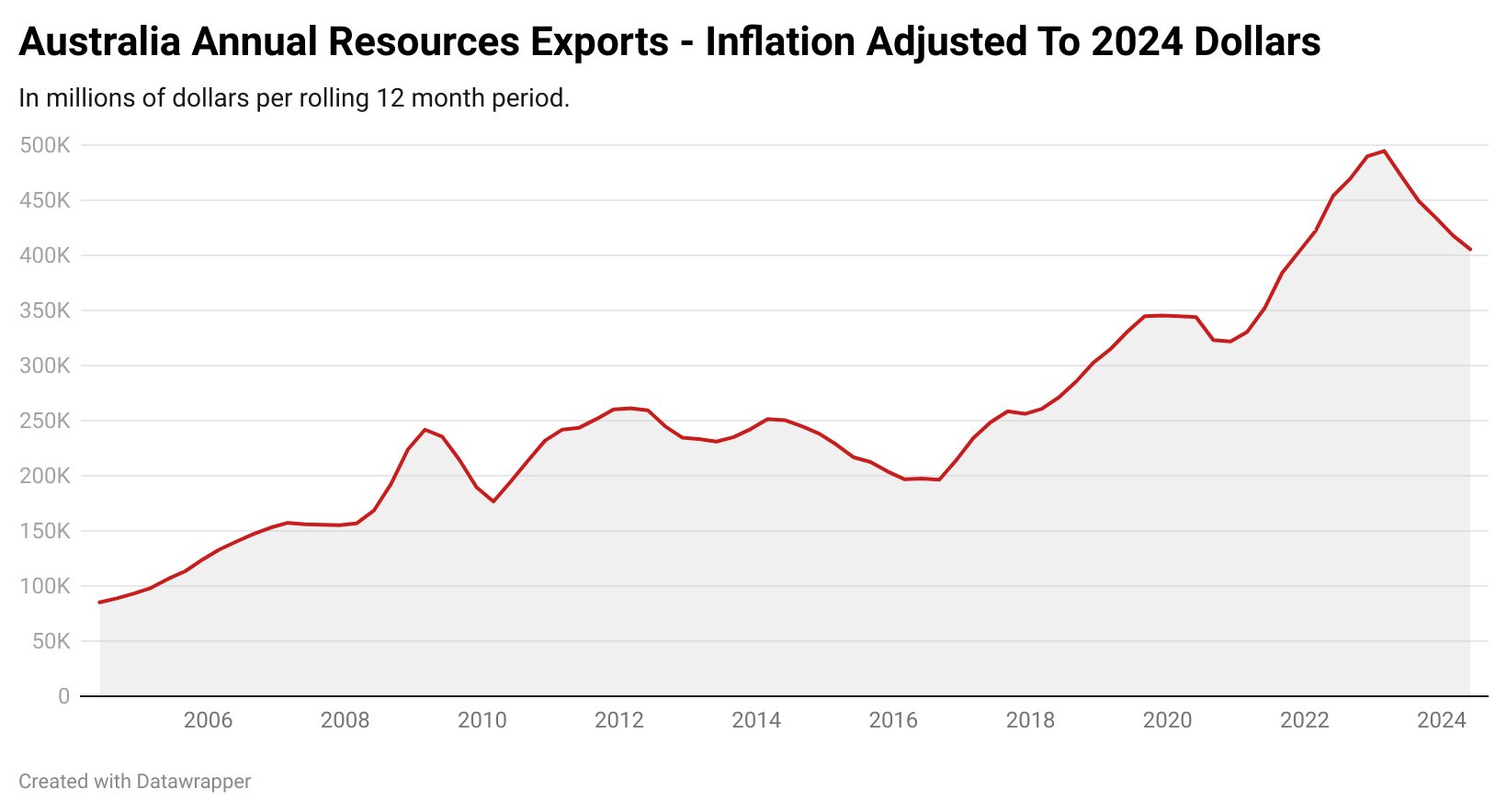

Over that time, the inflation-adjusted value of Australia’s resource exports has skyrocketed, with China being the number one destination for the nation’s exports of natural resources by a wide margin.

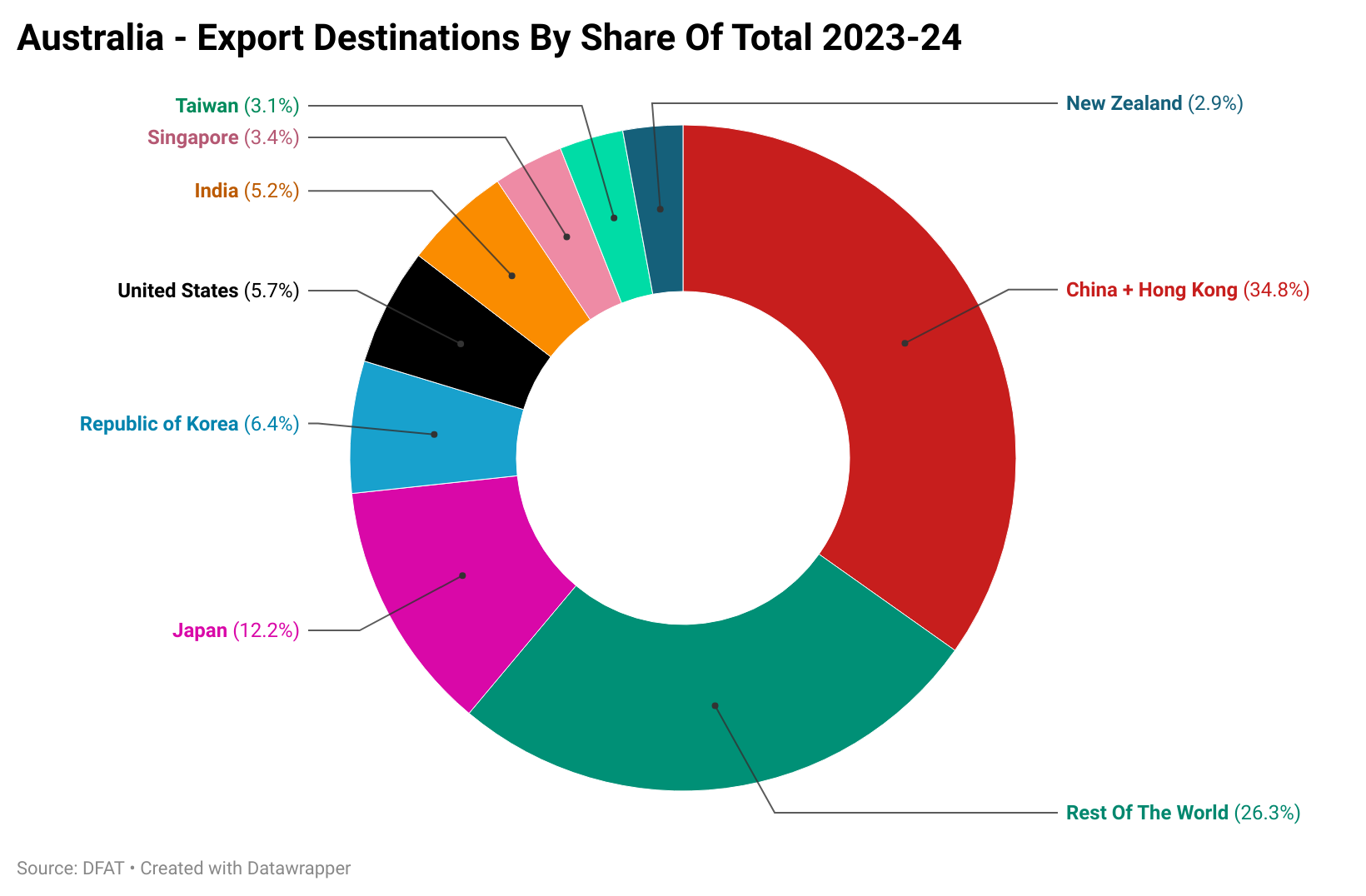

During the 2023-24 financial year, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade recorded China as being a larger recipient of overall exports than the next 5 nations (Japan, South Korea, the U.S., India, and Singapore) combined and then some.

Two of the nation’s primary exports over that time have been iron ore and coking coal, the most basic elements powering the industrial powerhouse that is China’s steelmaking industry.

Today, China is the world’s largest steel producer, literally outproducing the rest of the world combined.

But with such huge industrial capacity comes the requirement of finding a customer to consume that steel.

For the longest time, one of the main sources of consumption growth for steel was the Chinese real estate sector, providing the foundations for the largest homebuilding pushes in human history.

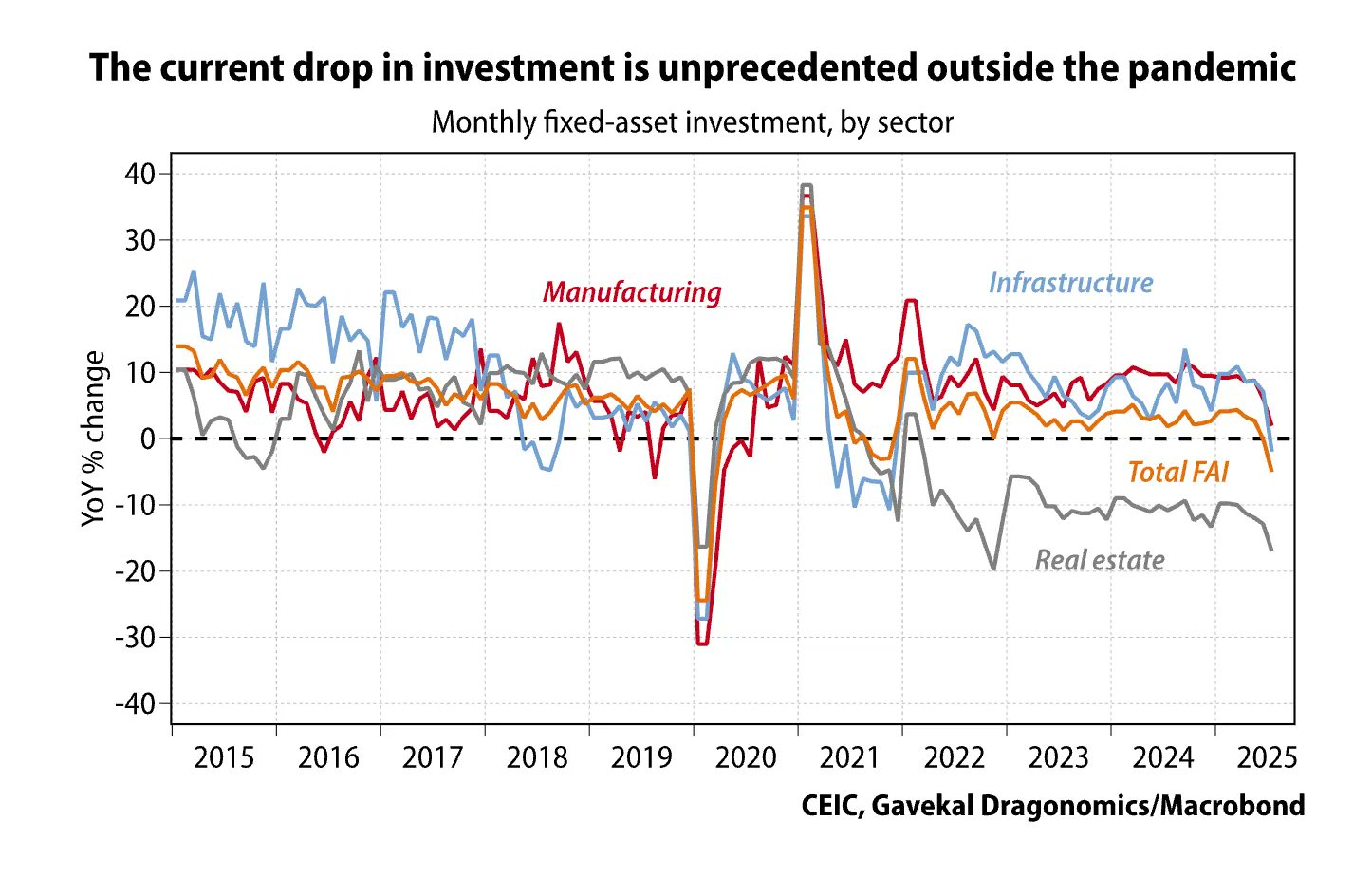

Now amidst the ongoing bust in the real estate sector, the level of steel consumption by this industry continues to fall to a greater degree with each passing year.

In the years since the construction bust became entrenched in 2022, infrastructure construction and investment in manufacturing have taken over as the driver of steel demand growth within the Chinese economy.

But with the release of the latest data on fixed asset investment, it was revealed that infrastructure investment had fallen into contraction in year-on-year terms for the first time since late 2021.

Meanwhile, fixed asset investment into the manufacturing sector has dropped off significantly, hitting its lowest level since a lockdown impacted 2020.

Source: Gavekal

Amidst the deterioration in fixed asset investment, the Chinese steel sector is increasingly reliant on exports to find purchasers for the still elevated levels of production.

How long robust steel export growth will persist in the face of the threat posed by cheap Chinese steel to local domestic steelmaking around the globe remains uncertain.

However, if the deterioration in growth in fixed asset investment in China persists, in time there just won’t be the scope for the rest of the world to absorb what would become excess steelmaking capacity.

For the primary provider of the fuel for that industry, Australia, this could be problematic.

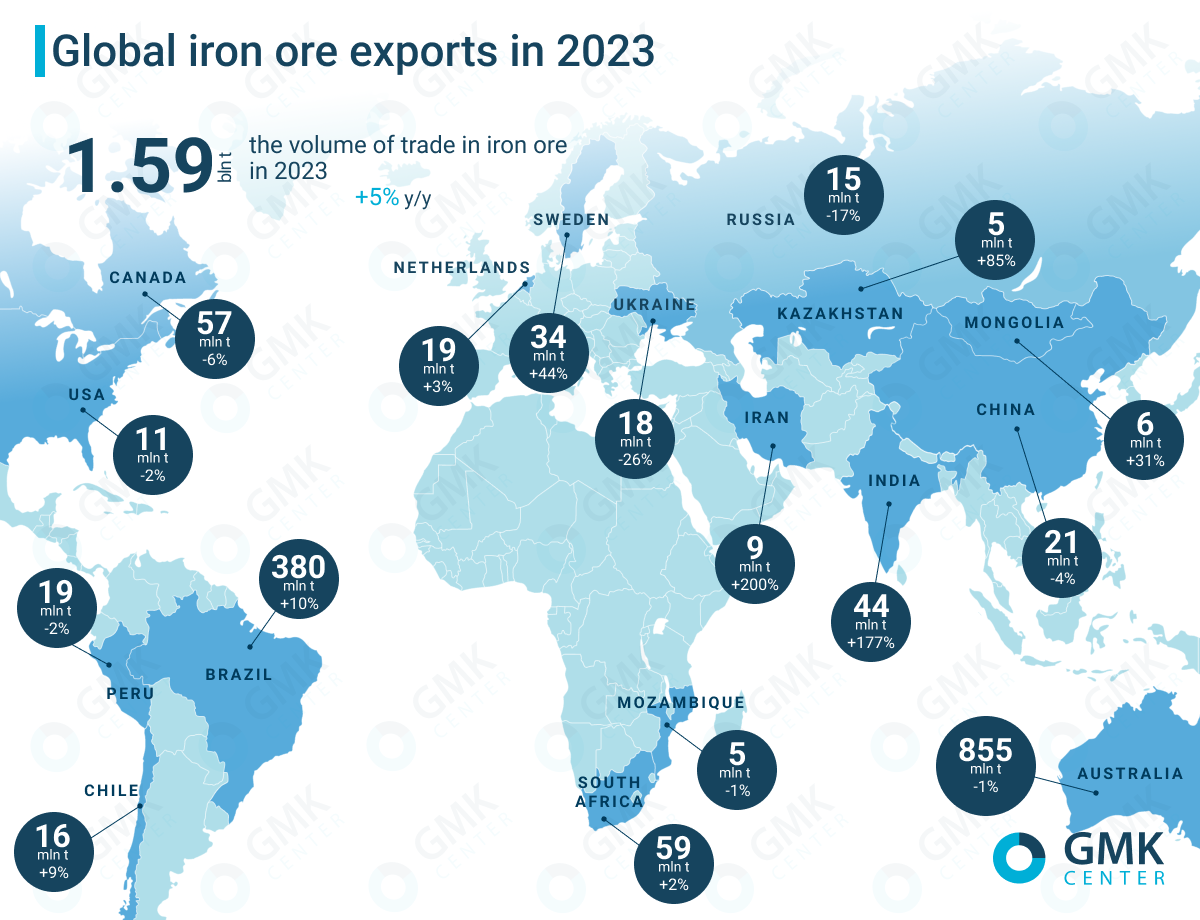

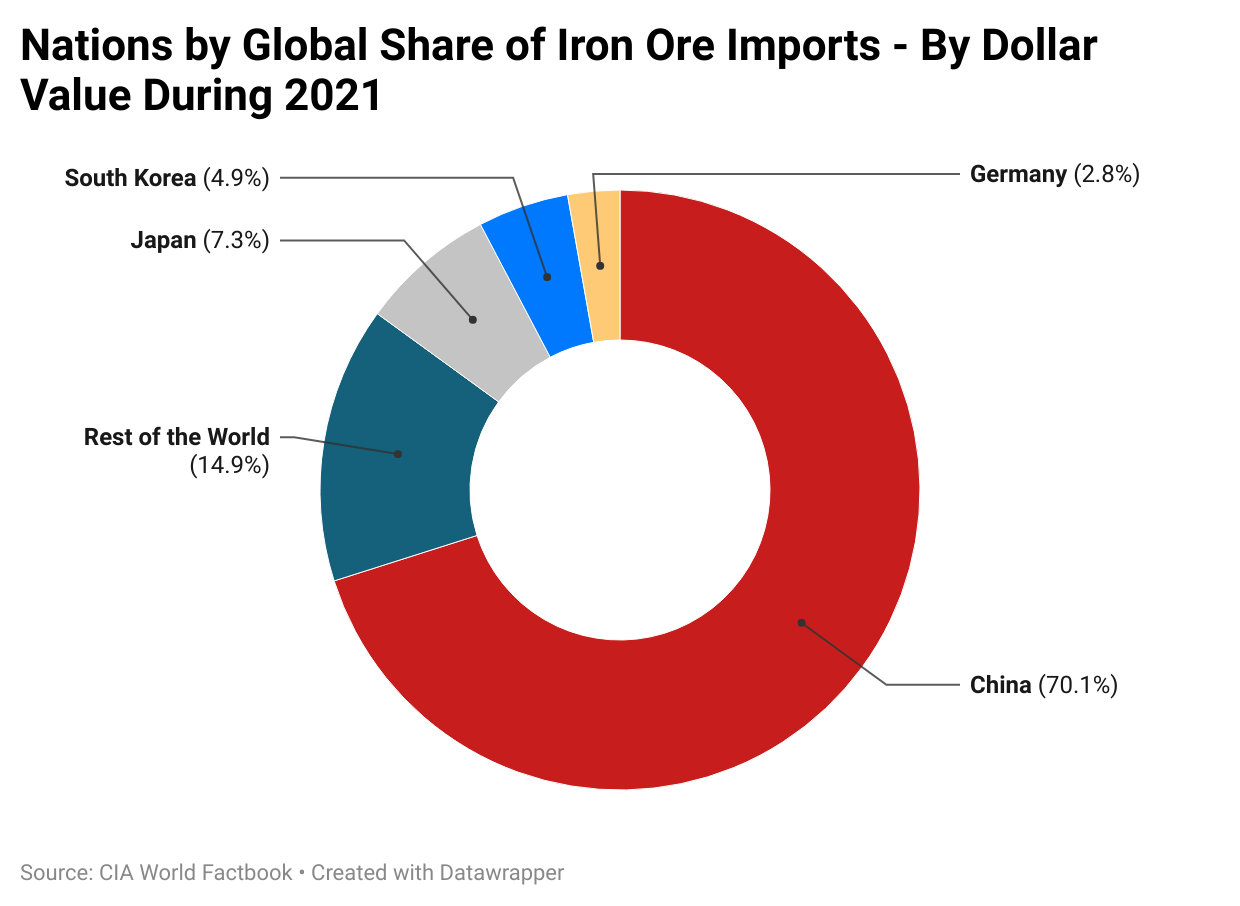

There would simply be no alternative if Chinese demand for resources like iron ore were to wane, with China importing more iron ore than the rest of the world put together.

Meanwhile, production at the joint Chinese and Rio Tinto-owned Simandou mega-mine in West Africa is set to kick off later in the year and then ramp up over 2026 and 2027.

This arguably leaves iron ore prices in a rather vulnerable position going forward in the absence of a catalyst for positivity.

As we close today, there is something of a silver lining to the challenges waning demand for Chinese steel may hold for Australia.

As one of the lowest cost and highest quality producers in the world, Australia’s mines will largely remain profitable and open, even if a fairly serious downside scenario were to be realised.

The bad news would be that in that scenario the price we receive for what are currently some of our nation’s most valuable exports, such as iron ore and coking coal, would be significantly lower than what state and federal treasuries have become accustomed to.

If that scenario were to be realised, the strategy of using larger government and higher levels of taxpayer-funded employment to support the economy would be swiftly brought into question.