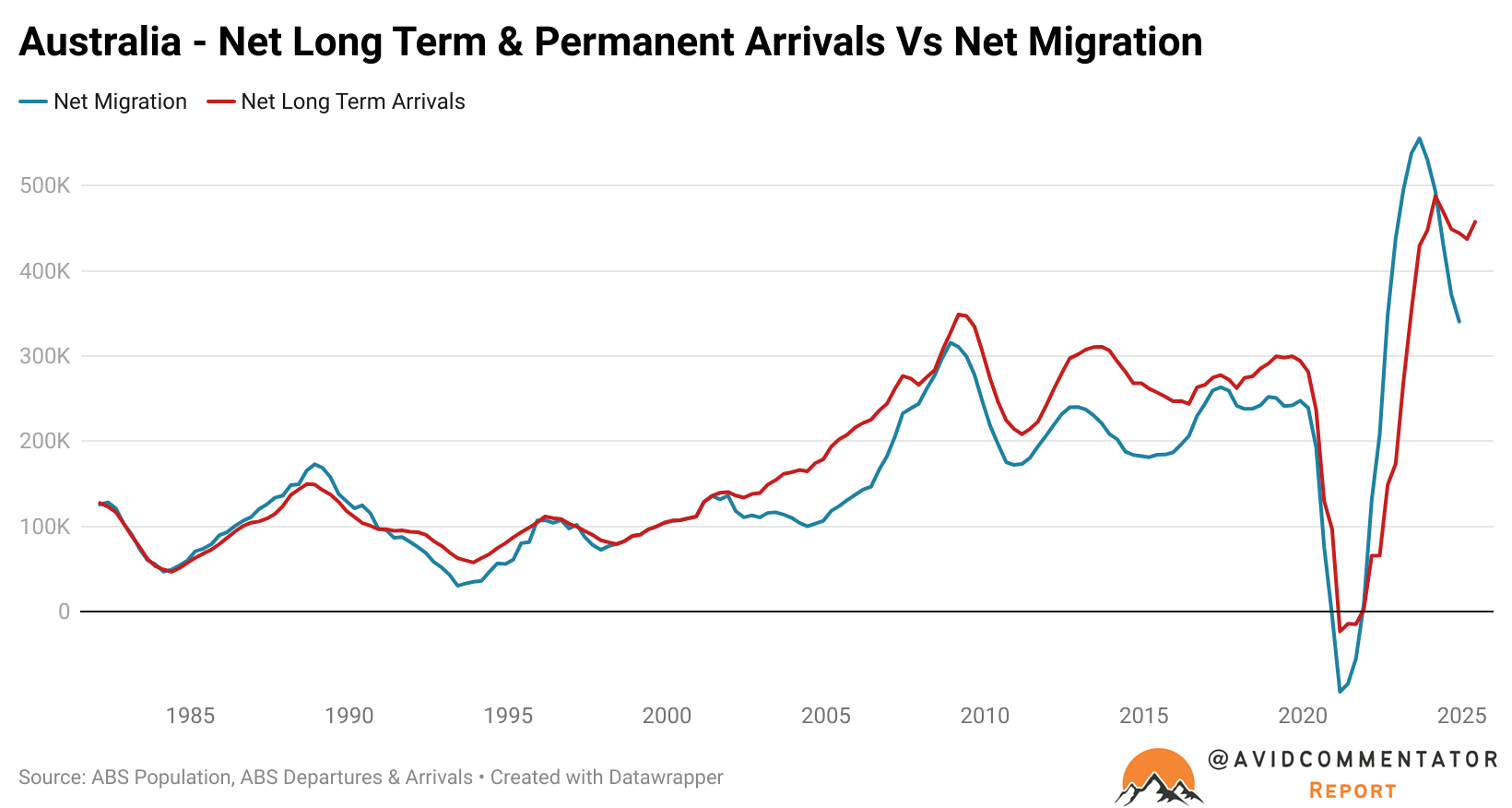

When the Morrison government handed down the 2022-23 federal budget in late March 2022, shortly before that year’s federal election campaign kicked off, it was projected that net overseas migration for the full 2021-22 financial year would be 41,000.

With only a little over 3 months remaining in that financial year at the time, it seemed like a fairly good bet on paper that Treasury’s estimates would at least be within the ballpark of the final figure.

Net overseas migration for the 2021-22 financial year ended up coming in at 207,900, not dramatically removed from 241,300 in the final full financial year before the pandemic, despite the fact that borders were only fully open for less than 5 months of 2021-22.

To put the scope of the forecasting miss into perspective, the additional 166,900 people the nation would admit in 2021-22 would drive demand for 66,000 additional homes, even using a relatively rough and perhaps conservative measure.

The failure to anticipate the dramatic growth in the migration intake wouldn’t stop there.

The forecast for 2022-23 was 235,000, yet came in at 538,300.

For 2023-24, the forecast was again 235,000, yet came in at 430,500.

For 2024-25, the original forecast was 260,000, with the latest figures up to the end of December showing net migration at 340,600 on a rolling 12-month basis.

According to an analysis by ABC’s Alan Kohler:

“That means at least 800,000 more people came to live in Australia over the past four years than Treasury anticipated. That’s more than three extra Hobarts.

So, there are that many more cars on the road than expected, that many more people looking for health care, and hundreds of thousands more kids in schools than expected.”

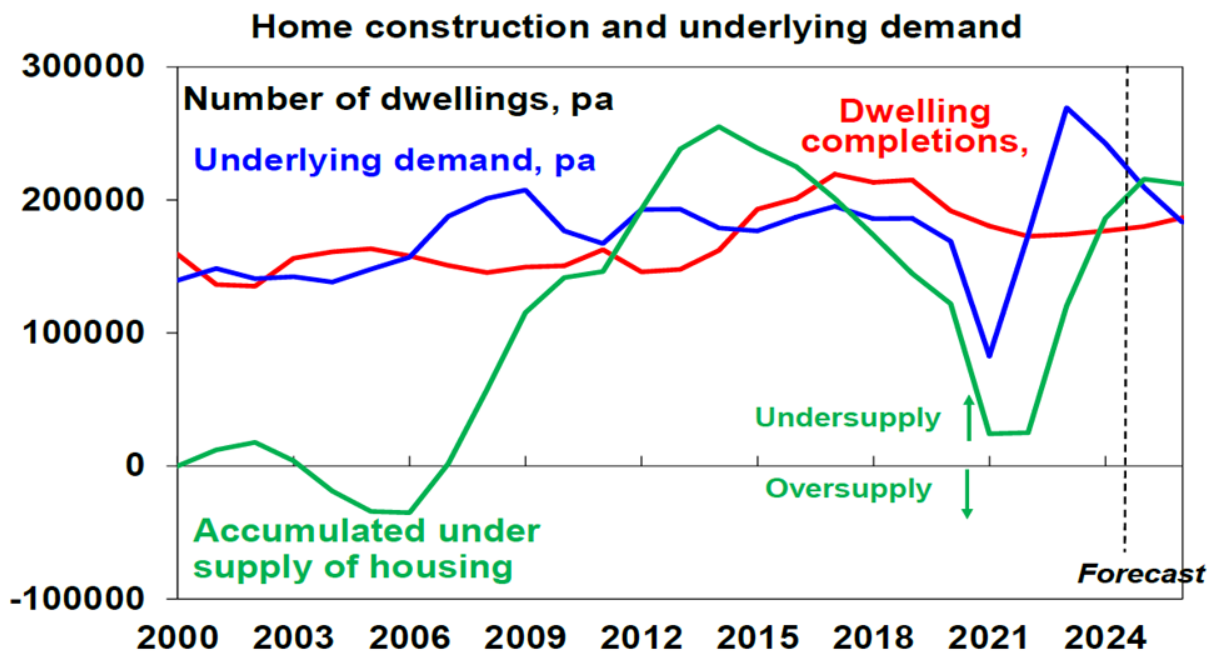

Kohler went on to conclude that based on a rough analysis that divides total population growth by 2.4, a proxy for the average household size and other factors, the nation was roughly 150,000 homes short over the last four years’ worth of data.

This echoes an analysis by prominent economist, AMP’s Shane Oliver.

“We’ve got a massive shortfall of housing in Australia relative to the number of people.”

“We estimate the accumulated housing shortfall to be around 200,000 dwellings at least, and possibly as high as 300,000 dwellings.” Oliver said.

Source: AMP

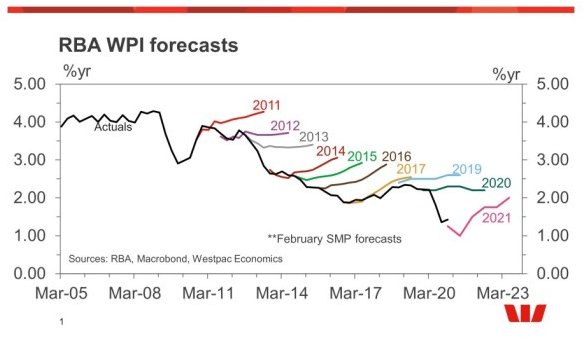

While the failure to accurately forecast has at times been a source of somewhat dark humour within the economics and finance community, most notably the repeated optimistic wage growth forecasts from the RBA during the 2010s, the reality is that not anticipating additional population growth to the tune of over three-quarters of a million people is far more damaging.

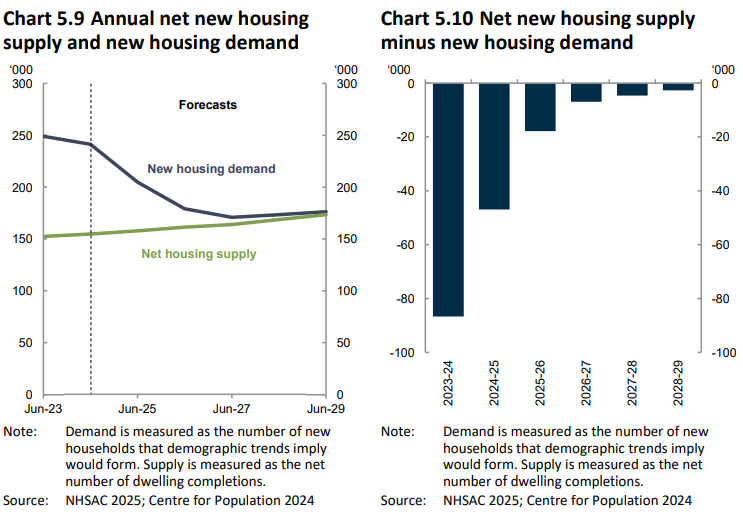

Meanwhile, the Albanese government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council forecasts that unless circumstances improve, there will not be a significant improvement in the housing shortage this decade.

Ironically, this situation relies on the assumption that the population growth and migration forecasts from the Centre for Population will be accurate throughout the entire period of forward estimates.

The failure of Treasury to forecast the unprecedented surge in net migration and the Albanese government’s failure to get migration swiftly under control has left the nation with a housing shortage that will likely persist well into the next decade.

Ultimately, the people of Australia, particularly those who don’t own homes, will be paying for that failure in different ways long after Prime Minister Albanese exits the lodge for the final time on his way to retirement.