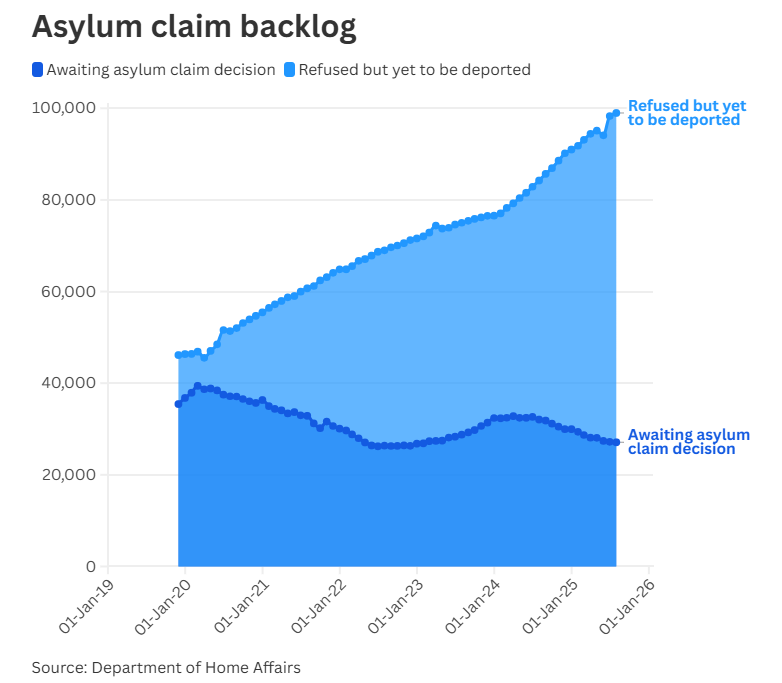

Recent figures from the Department of Home Affairs revealed that almost 100,000 asylum seekers had their claims for asylum in Australia rejected, yet they remained in the country.

This includes an estimated 50,000 who have completely exhausted their avenues for appeal.

This figure has been heavily driven by individuals formerly on student visas applying for asylum, with Dr Abul Rizvi stating to News.com.au’s Frank Chung that it was “undoubtedly” a factor.

Rizvi went on to conclude that the government must take urgent action to clear the deportation backlog that has been growing for a decade.

“We want to at least stabilise it, otherwise you end up with a massive underclass and it impacts social cohesion, and eventually you get some strongman leader like Trump saying, ‘I’m going to fix it.’” Rizvi said.

Despite there being tens of thousands who should have been deported, the number of failed asylum seekers actually deported over the 12 months to June comes to just 162, not even enough to fill a single average-sized Australia-bound international airliner.

As a result of this lax approach to deportations, the number of asylum seekers who have had their claims rejected but remain in the country has risen from 84,235 in July last year to 98,979 as of the end of July this year.

According to an analysis from News.com.au:

“Home Affairs data shows India and China—Australia’s two top sources of international students—flooded the system with applications as thousands more were overwhelmingly rejected.

Indian nationals made 2596 applications for onshore protection visas, while in the same period 5633 existing claims were rejected—accounting for more than one in five of all refusals.

Between 42 and 60 Indians were granted asylum, or 1-1.5 per cent of all approvals.

Chinese nationals made 2494 applications and 3538 were refused in that period. Around 290 were granted asylum, or about 7 percent of the total.”

Yet, despite this becoming a mounting issue, costing taxpayers millions of dollars a year and these individuals occupying tens of thousands of homes amid a rental crisis, it remains inadequately addressed.

When confronted with the challenges presented in deporting such a large number of people, successive governments have largely ignored the issue.

In the words of Dr Rizvi:

“Most governments, when confronted with those facts, have just said, ‘Let’s let it go through to the keeper.”

The “Unsung Hero” and Fraud

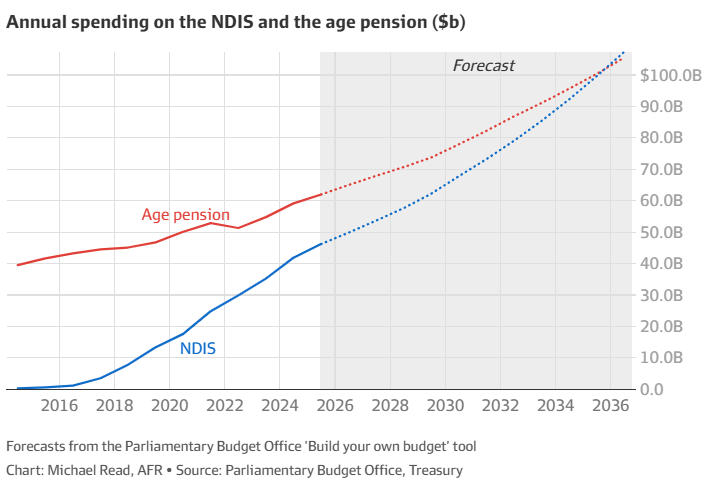

Meanwhile, in the NDIS, which former Opposition Leader and NDIS Minister Bill Shorten called the “unsung hero of low unemployment and employment growth over the last decade since its creation.”, there are concerning signs of widespread malpractice.

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA), which is responsible for overseeing the NDIS, concluded in a 2023 report that an estimated 6 to 10% of NDIS outlays could be “for non-compliant, fraudulent or incorrect claims.”

Based on the estimated cost of the NDIS for 2025-26 of $52.3 billion, this puts the bill “for non-compliant, fraudulent or incorrect claims” at between $3.13 billion and $5.23 billion per year.

Chart from The AFR

In an appearance before a Senate Committee in 2024, NDIS Integrity Chief John Dardo shared an internal analysis that showed 90% of plan managers who wrangle funding for up to 100 participants (~900 of 1540 managers in total in this category) displayed “significant indicators of fraud”.

However, despite widespread reports of “significant indicators of fraud” and more than 21,000 tip-offs alleging fraud each year, the latest reports from the NDIA reveal that there are currently only 19 people being prosecuted for fraud.

During his appearance before the Senate Committee, Chief Dardo concluded that:

There was “not sufficient judiciary (capacity) to process the cases we have in the pipeline in the country”.

“Prosecution is not the answer. It’s too late,” Dardo said.

“The end game can’t be prosecution. We’ve got to get to prevention.”

The Takeaway

Between these two rather serious issues alone, successive governments have wasted potentially billions of dollars’ worth of resources and occupied valuable spaces in the nation’s homes that could have contributed to alleviating the rental crisis.

While both of these issues present practical, political, and economic challenges in their own way, making significant progress to address both would be deeply in the national interest.

Making the NDIS more sustainable would ensure its continued operation for those who genuinely need support, while freeing up significant resources to be deployed elsewhere.

Meanwhile, clearing the massive backlog of deportees could release as many as 40,000 homes back onto the open market, and more careful vetting of students in the first place could prevent this weak point in Australia’s migration and judicial system from continuing to be exploited.