With each rate cut, commentators discuss how it will impact the housing market, make borrowing more accessible, and enable more people to enter the market.

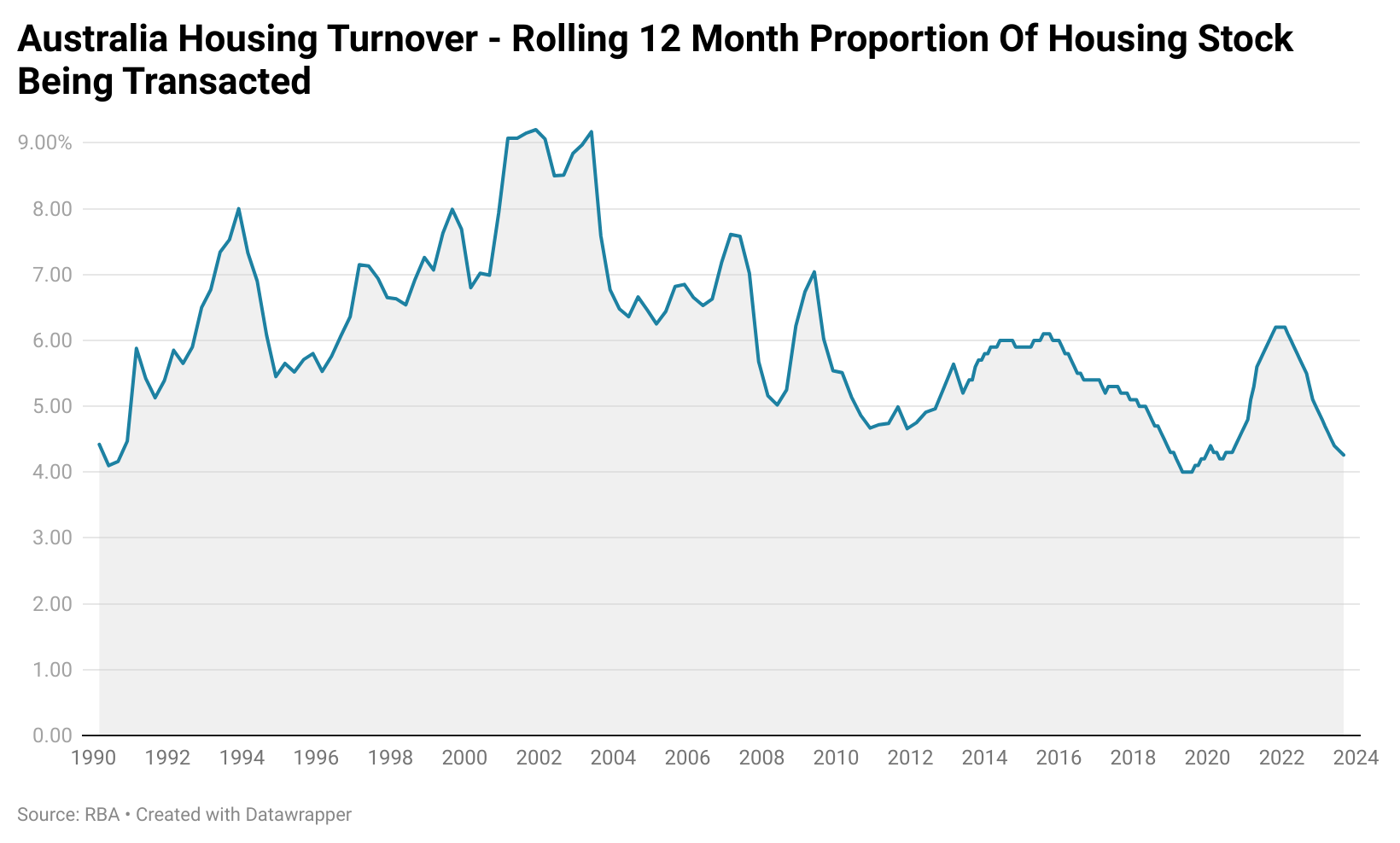

Yet, when you look at the numbers on a long-term time horizon, the era of low interest rates has resulted in fewer people entering the market and less mobility for households to move geographically.

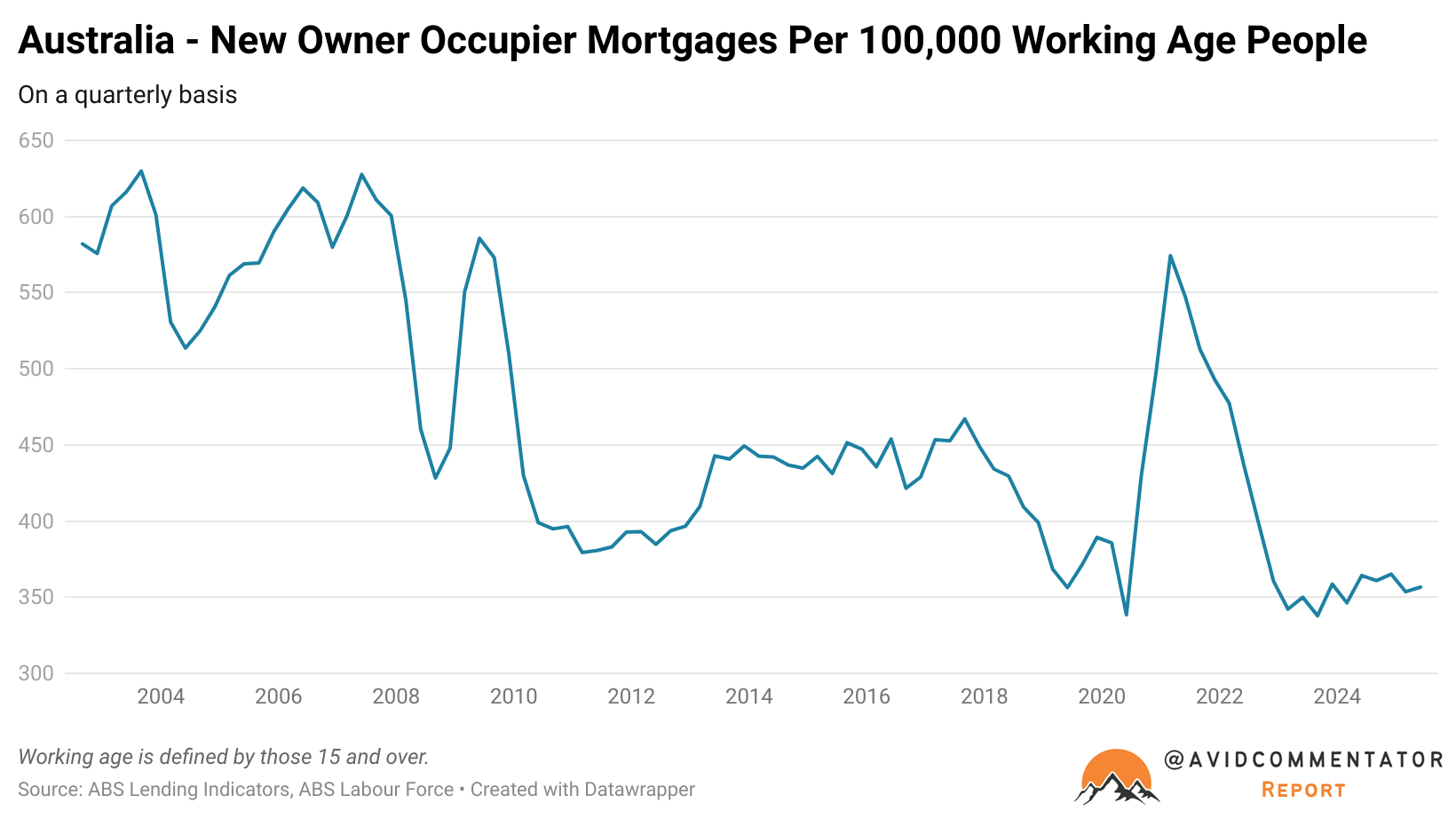

Part of the issue is simply that loan sizes have grown larger and larger with time, so while the total volume of credit flowing to new mortgages in dollar terms has risen, that is not representative of more homes being purchased.

To put this into perspective, there were 19.0% more new mortgages written for owner-occupiers in the June quarter of 2003 than there were in the June quarter of this year.

There is also the issue of population growth and the expansion of the overall housing stock, both of which, in isolation, should lead to an increase in transactions.

But when the number of new owner-occupier mortgages is deflated by the number of working-age people over the length of the current ABS data set, it reveals that the level of new mortgage creation for owner-occupiers remains deeply depressed and not too far removed from the lows seen during the absolute height of the pandemic.

There is no one issue where responsibility can be assigned.

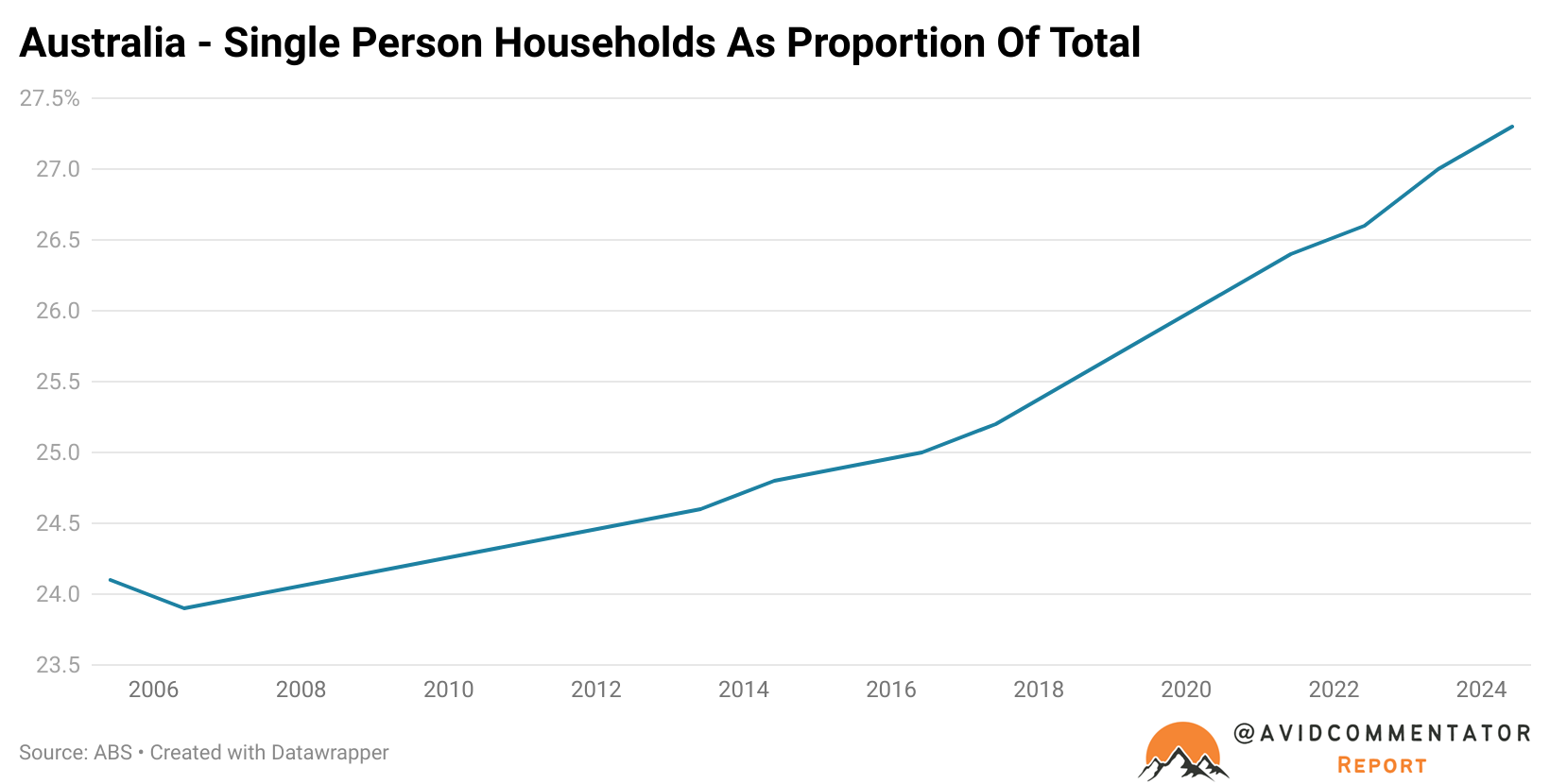

Part of it comes down to demographics. With the population ageing, an increasingly large proportion of Australians are in homes they intend to remain in until they pass.

There is also the issue of investor participation in the market, with 37.6% of housing credit flowing to property investors.

Population growth, in particular working-age population growth, which is heavily driven by migration, also plays a significant role, constantly expanding the number of prospective first-home buyers, most of whom that stay for the long haul will eventually purchase a home.

Overall, there are elements of the situation that were unavoidable, such as an aging population and changing household demographics.

Although it was obvious that these shifts were coming for decades, policymakers should have been better prepared for them.

On the other hand, many of the aspects making getting into a home more challenging, such as greater competition from a swiftly growing base of prospective first-home buyers and property investors, have been entirely self-inflicted by policymakers.

Changes could be made tomorrow to address the impact of both of those factors to ensure that more Australians become homeowners and acquire the necessary foundation for a secure retirement.

Ultimately, the writing has been on the wall for a long time and the downside consequences are clear for policymakers. But there appears to be little appetite to address the issue in a way that will result in meaningful positive change.