Recently, the issue of how migration is measured has exploded into the headlines, with several media outlets and other organisations, including 2GB, the Daily Mail, the Institute of Public Affairs and Macrobusiness, receiving correspondence from the ABS on the issue.

To quote from Leith’s article on this from last week:

On Wednesday evening, I received an email from an Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) media officer suggesting that I have misled the public by quoting the ABS’ monthly net permanent and long-term arrivals data.

The article where I have purportedly misled can be read here.

The email, presented below with the officer’s name removed, claimed that it is “inaccurate and misleading to use” the monthly net permanent and long-term arrivals data as a “measure of migration”.

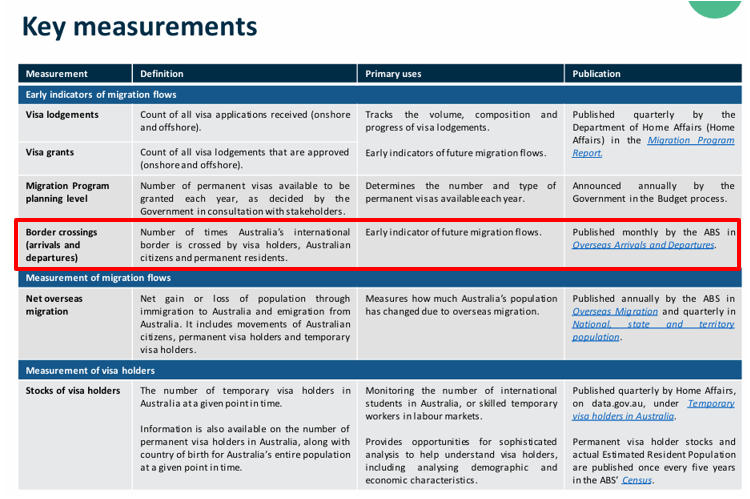

The federal government’s own Centre for Population certainly doesn’t think so, with that organisation producing a report in which it’s stated that border crossings (arrivals and departures) are an “early indicator of future migration flows”. More on that in detail from last week’s article here.

Source: Centre for Population

In order to better get a handle on this issue, we’ll be looking at the net long-term and permanent arrivals (net arrivals for today’s purposes) data set, both on its own and contrasting it with net overseas migration over the last 45 years.

In a vacuum

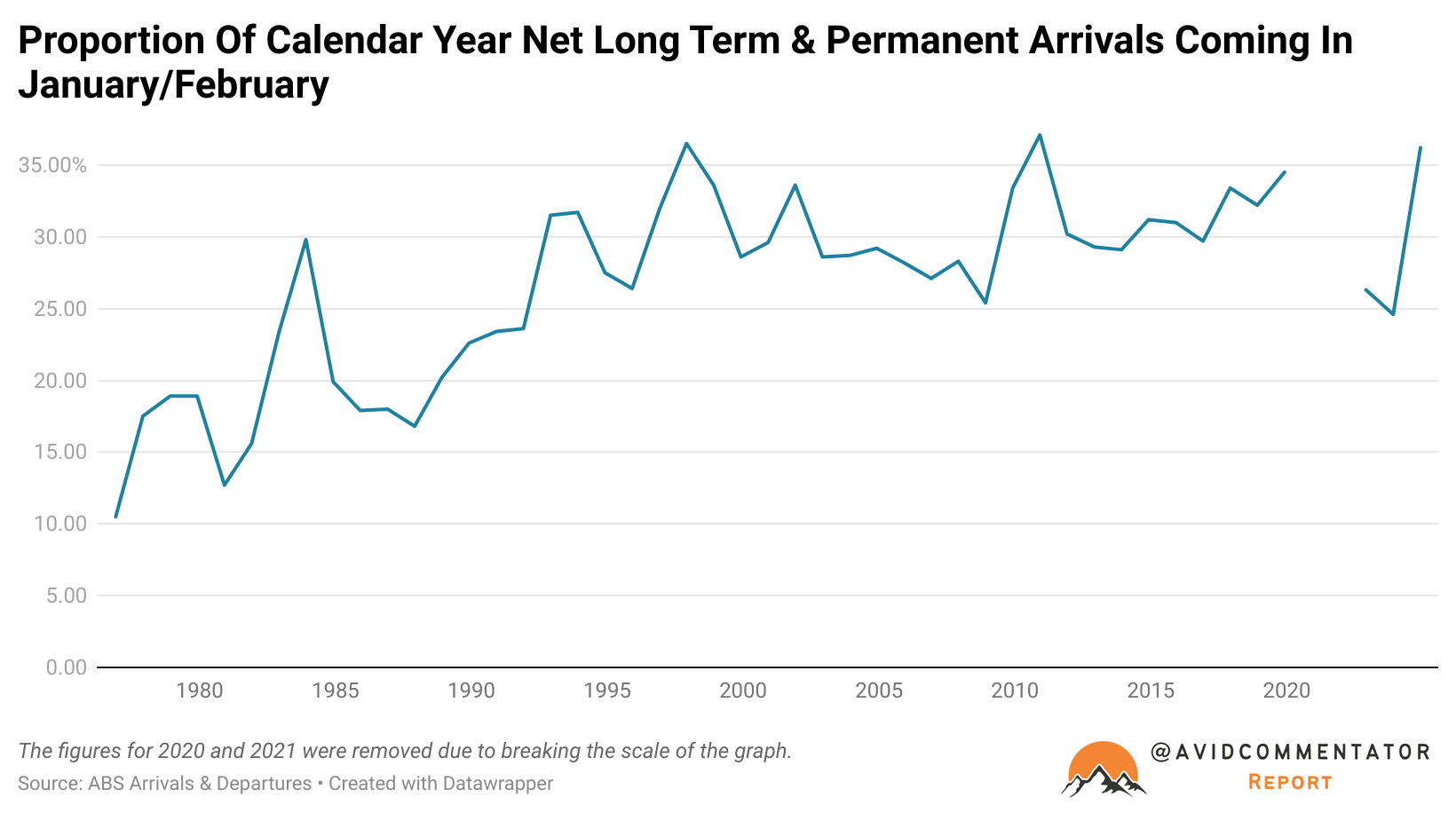

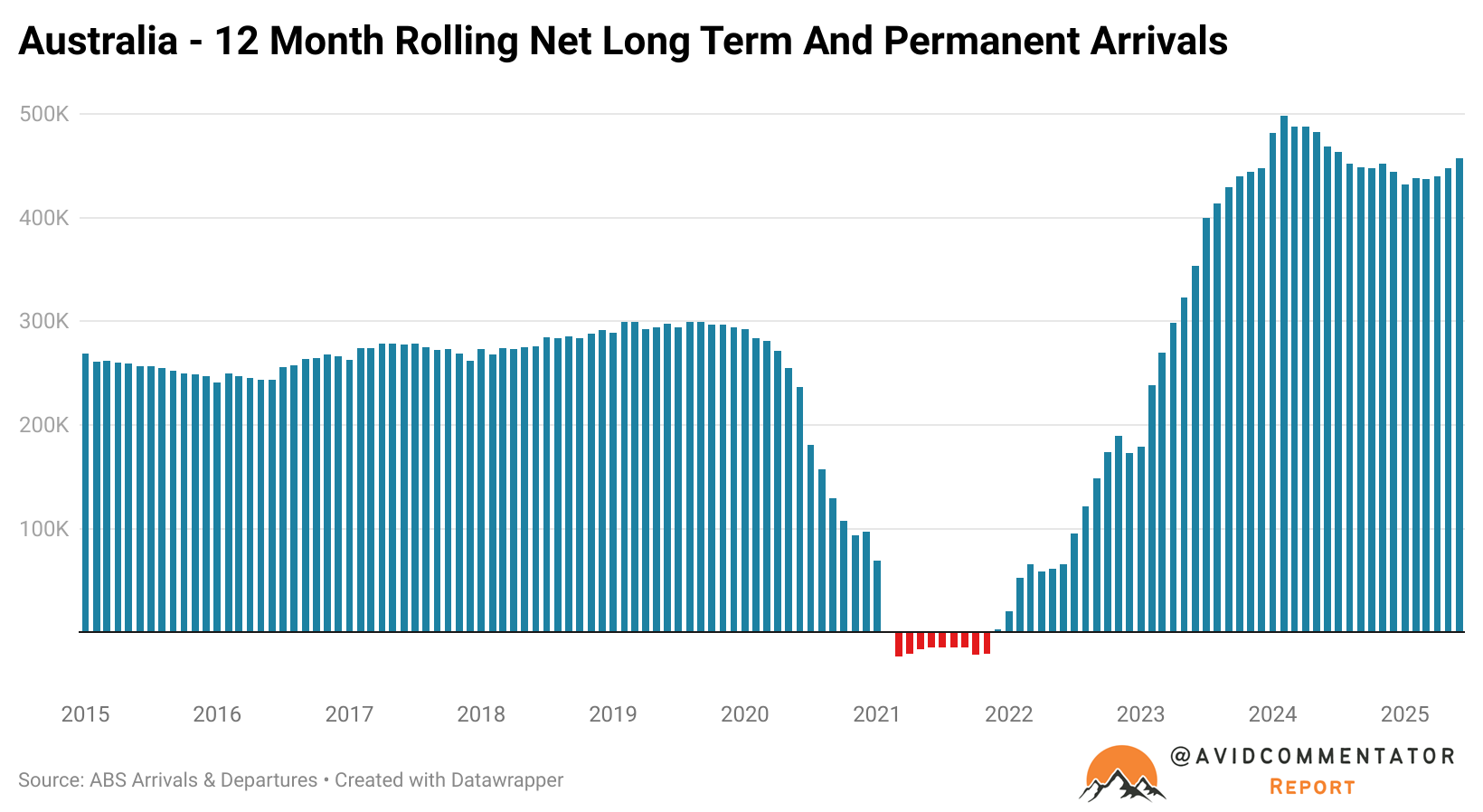

Given that net long-term and permanent arrivals data set is not adjusted for seasonality, it is highly volatile, with the start of the year seeing by far the largest proportion of net arrivals.

For example, the net arrivals of January and February 2024 represented 36.2% of the total for the entire calendar year 2024.

While the early months of a new year are arguably the ideal time to make a new start in a new nation more broadly, the rise of international students as one of the main drivers of net arrivals has meant that over time the proportion of total arrivals for the year arriving in the early months has continued to grow.

For this reason, it’s best to use the data on a year-to-date or a rolling annual basis to ensure that one is comparing apples with apples so to speak. Unless, of course, one has the ability and modelling experience to seasonally adjust the data.

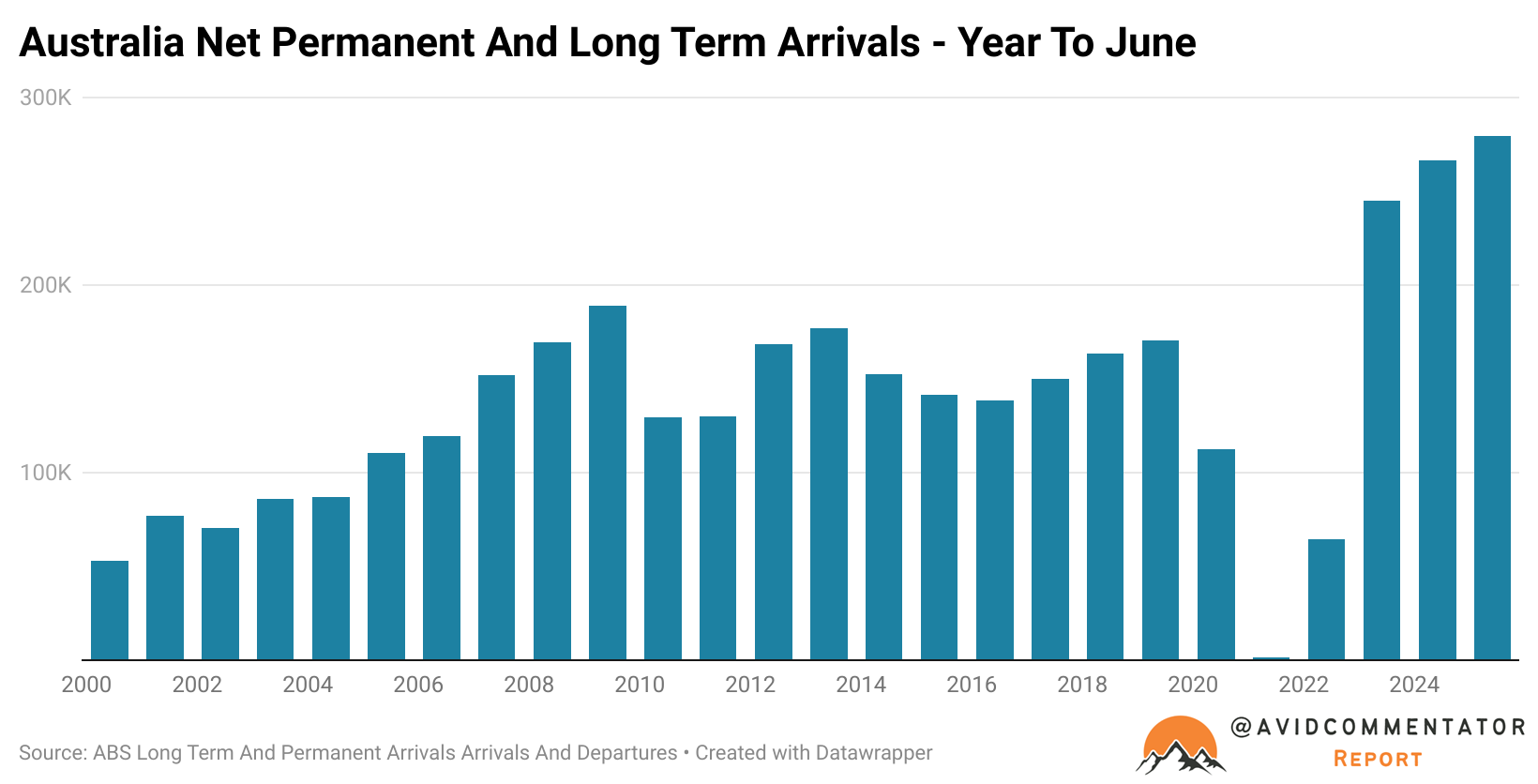

If we look at the current year’s figures to date, it reveals that in the year to June, Australia had seen 279,460 net long-term and permanent arrivals, the highest year-to-date figure since records began in the mid-1970s.

When the focus is shifted to a rolling 12-month figure, it reveals that there have been 457,560 net arrivals in the 12 months to the end of June.

It’s notable that between February 2024 and January 2025, the rolling 12-month number of net arrivals fell from 498,270 to 432,400.

However, since January, net arrivals have reaccelerated, rising by a bit over 25,000.

Net Long-Term & Permanent Arrivals Vs Net Overseas Migration

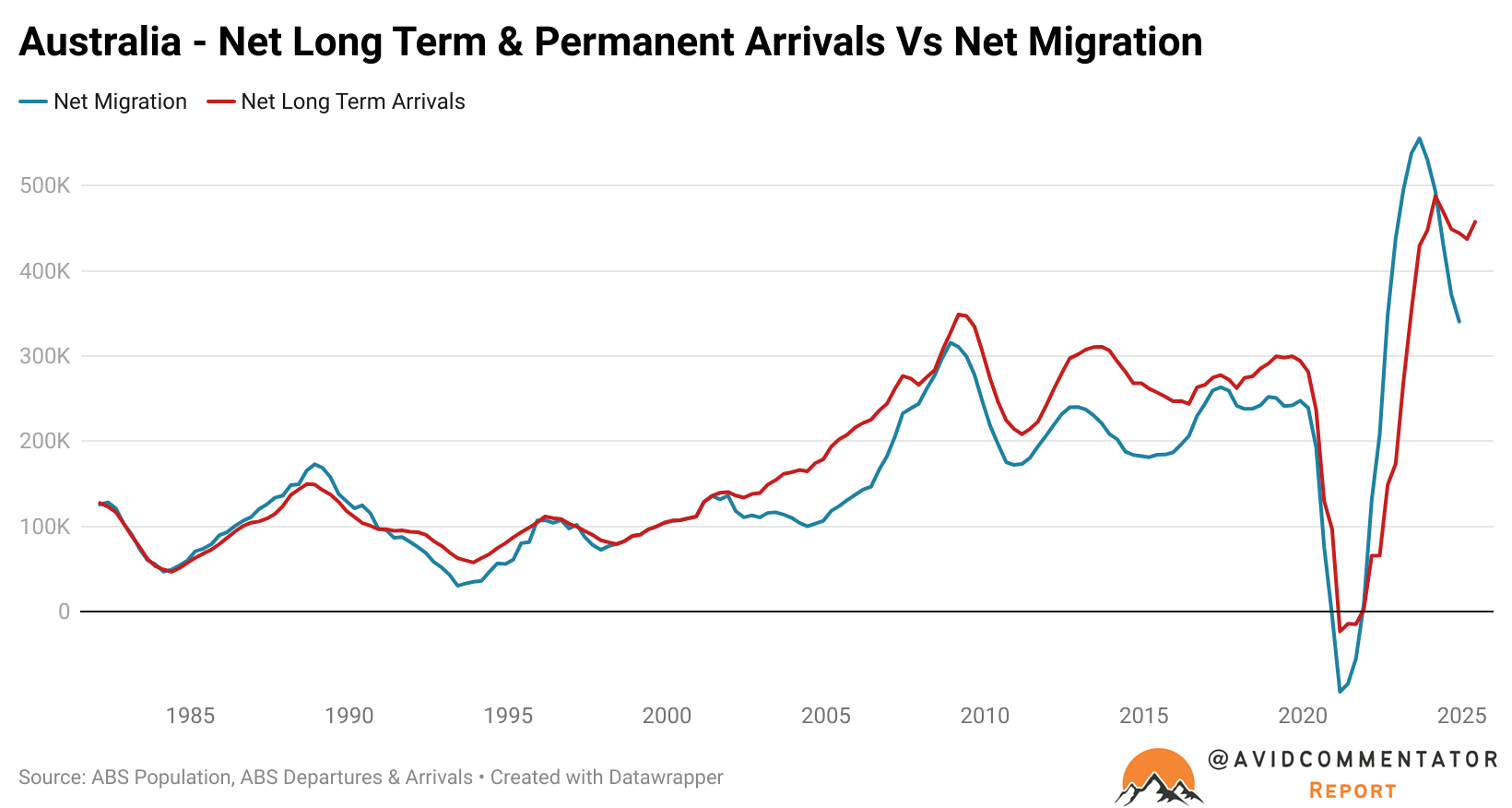

Looking at a chart of rolling annual net long-term and permanent arrivals versus net overseas migration since comparable quarterly records began, a clear directional relationship between the two is revealed.

While it’s far from a 1-for-1 perfect proxy for net overseas migration, historic moves higher in net long-term and permanent arrivals have, in time, generally been reflected by a move higher in net overseas migration.

It is here that it’s worth noting the data lag between the two metrics.

Prior to the release of the next quarterly migration figures from the ABS on the 18th of September, the latest available data point only covers up to the end of December.

Meanwhile, today, the latest net long-term and permanent arrivals data covers up to June and by the time the net migration data is released, the July net arrivals figures will be available.

It is this lag that prompts economists, journalists, and analysts alike to use the net arrivals data to at least gain some perspective on whether migration is likely to accelerate or decelerate from its previously reported level.

Ultimately, the net long-term and permanent arrivals data set is exactly what it says it is and has provided something of a touchstone for the future path of migration for decades, even at federal government agencies such as the Centre for Population.