Last month the ABS announced that it would not be releasing the 2023-24 Survey of Income and Housing due to data collection issues.

In the ABS’ own words:

“Despite work to address these issues, the data did not meet the ABS’ high standards for official statistics and will not be released.

This decision means that the following products will not be released in 2025:

Deputy Australian Statistician, Dr Phillip Gould, said: ‘As the ABS modernises, we’re developing new ways to collect information to improve response rates and make it easier for people to complete our surveys.

‘This is partly because collecting data from households has become more difficult and costly in recent years. This is being experienced by statistical offices around the world.”

With these two data releases falling by the wayside, not to be released until mid-2027 at the earliest, observers of the Australian economy at a household level face an absolutely enormous gap between the last covered period in 2019-20 and the middle of 2027.

The blind spot this will create is huge, as these are two of the ABS’s most important data releases.

We will remain in the dark on vital questions, including household income by demographic, home ownership rates by demographic, housing costs by demographic and a plethora of other indicators arguably required for any serious push to address the housing crisis and productivity within the economy.

To be completely fair to the ABS, there have been issues with securing adequate funding for a long time now.

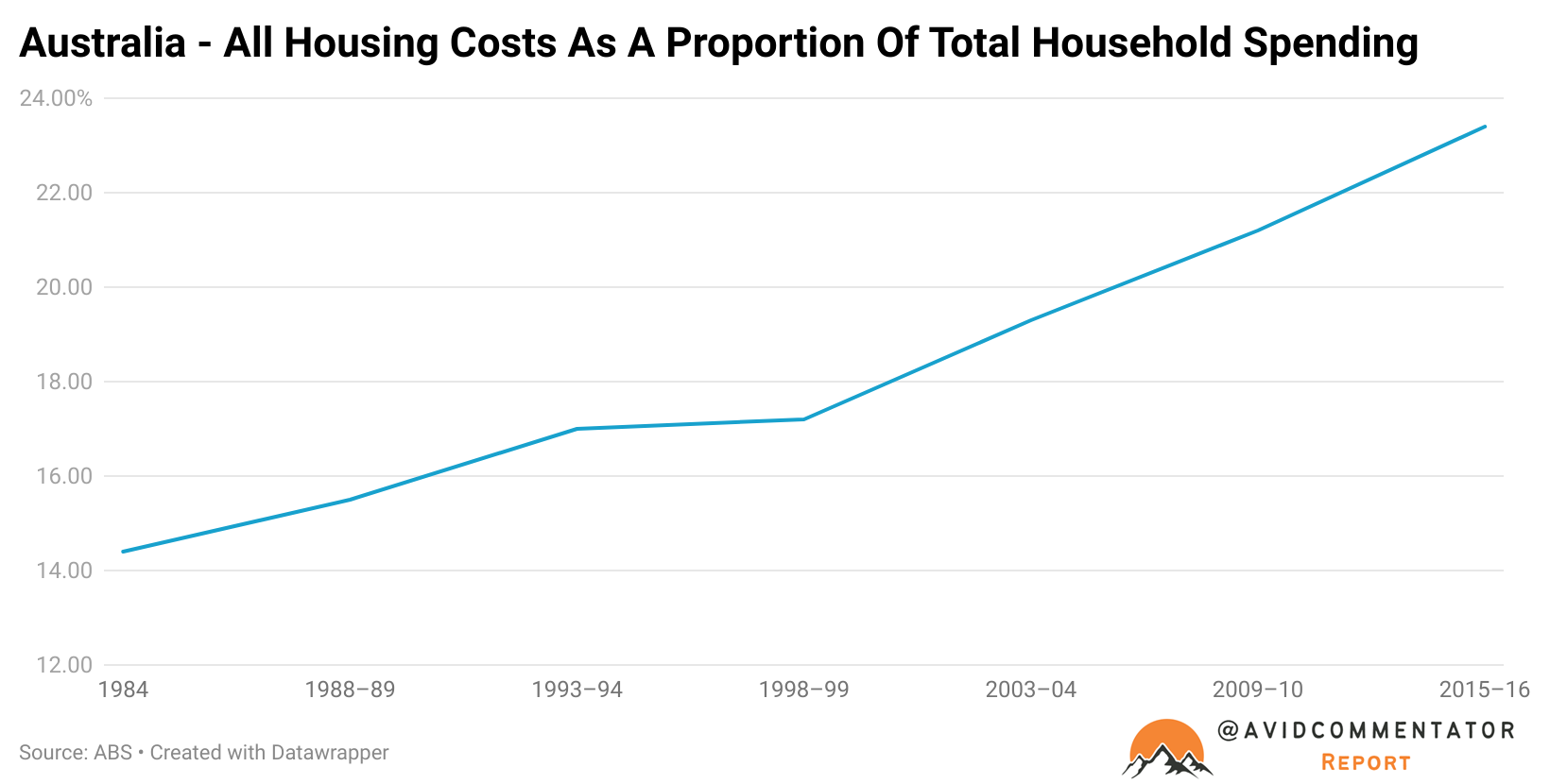

Meanwhile, data releases such as the Household Expenditure Survey (which goes back over 40 years) have seemingly ceased, with the last covered period almost a decade ago. This is a shame as this data provided a fascinating insight into spending patterns within the economy, showing the evolution of different categories of household consumption over time.

It recently proved very useful in illustrating how dramatically the spending of households on housing had risen over time, placing a significant drag on the economy.

At the same time, other data releases, such as the monthly housing finance report, have been shifted from monthly to quarterly, leading to significantly longer wait times between data releases and impacting the RBA’s ability to read shorter-term shifts in the appetite for housing credit.

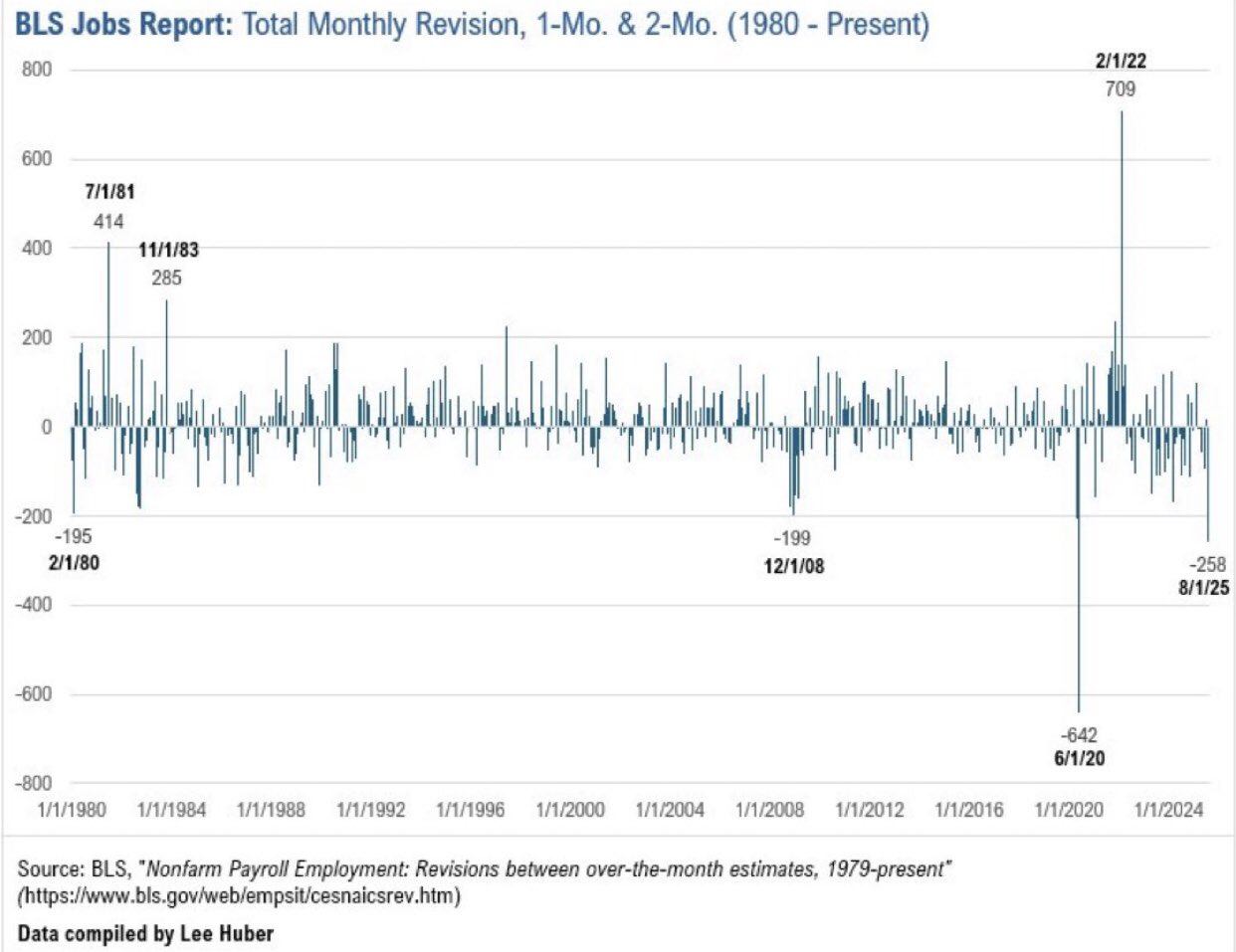

All that being said, issues with government data releases are not a phenomenon unique to Australia, as illustrated by the recent firing of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Chief by President Donald Trump.

President Trump was deeply displeased to see the large downward revisions in employment growth, with the total level of employment being revised down by 258,000 over the prior two months of data.

Source: Lee Huber

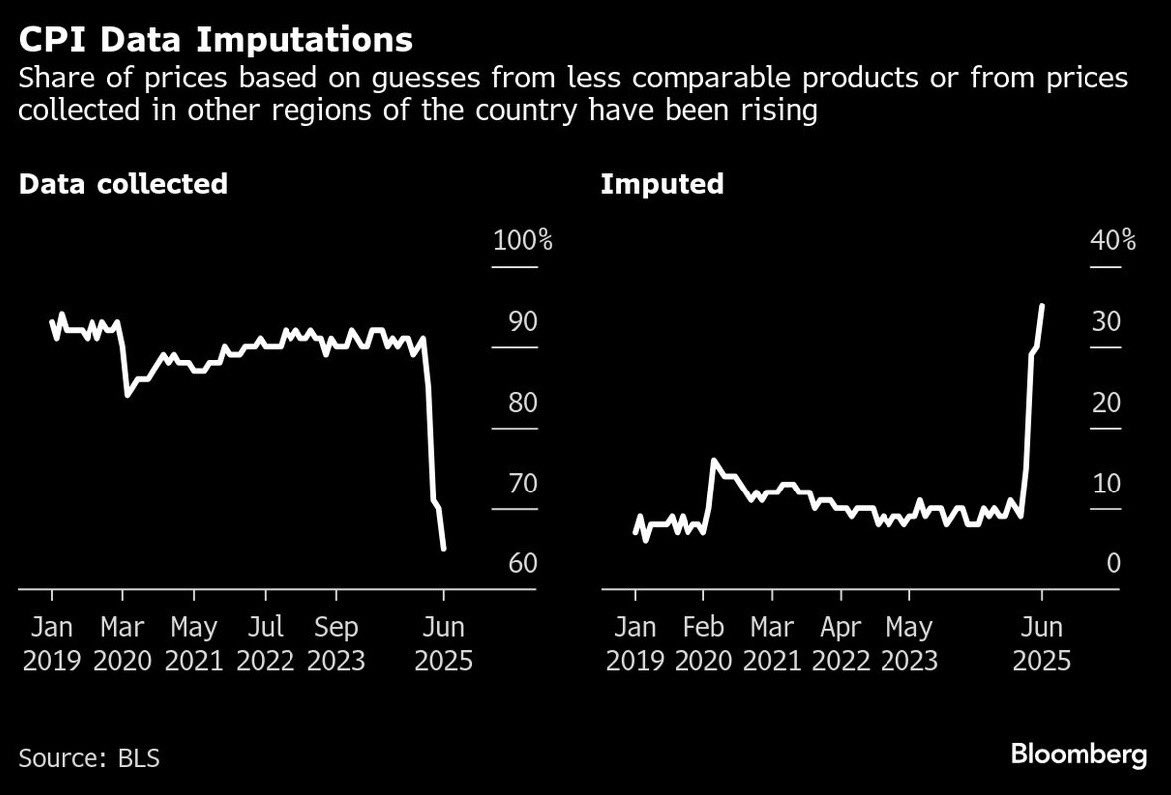

One of the major issues faced by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the ABS is people responding to their data requests and surveys.

For example, the proportion of the U.S. CPI that is estimated instead of being based on hard data has risen from around 10% in 2024 to 35% today.

The various statistics agencies from London to Canberra clearly need to make a change. Otherwise policymakers are effectively driving a car in reverse with a broken demister.

But until that day comes, we are increasingly flying blind, lacking some of the most important hard data on the true scale of the challenges faced by everyday Australians.

This is data that could help drive the much-needed call to action as the fortunes of more and more Australians fall by the wayside.