One could write an entire book on all the various drivers of Australian economic ruin. Today we will be taking the usual data-driven approach to examine the big three, in my view.

Housing Is The Economy

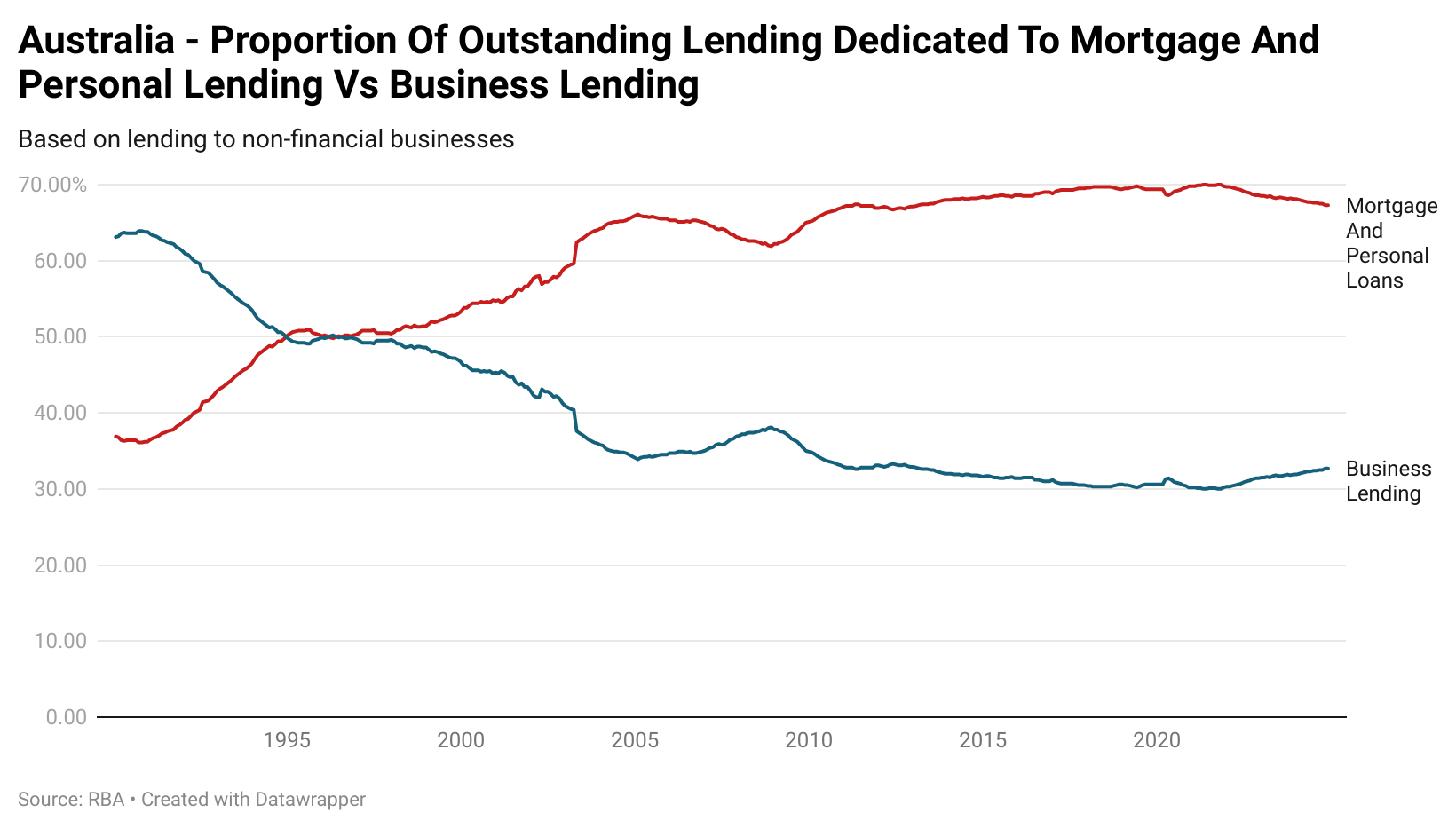

Back at the dawn of the 1990s, business lending was getting on for two-thirds of all outstanding bank lending to households and businesses.

Since then, the balance has been completely flipped in the other direction, with more than two-thirds of outstanding lending in these categories flowing to mortgages and personal loans.

In short, the housing market has increasingly acted like a vacuum cleaner sucking up capital that could be directed toward starting or growing productive enterprises.

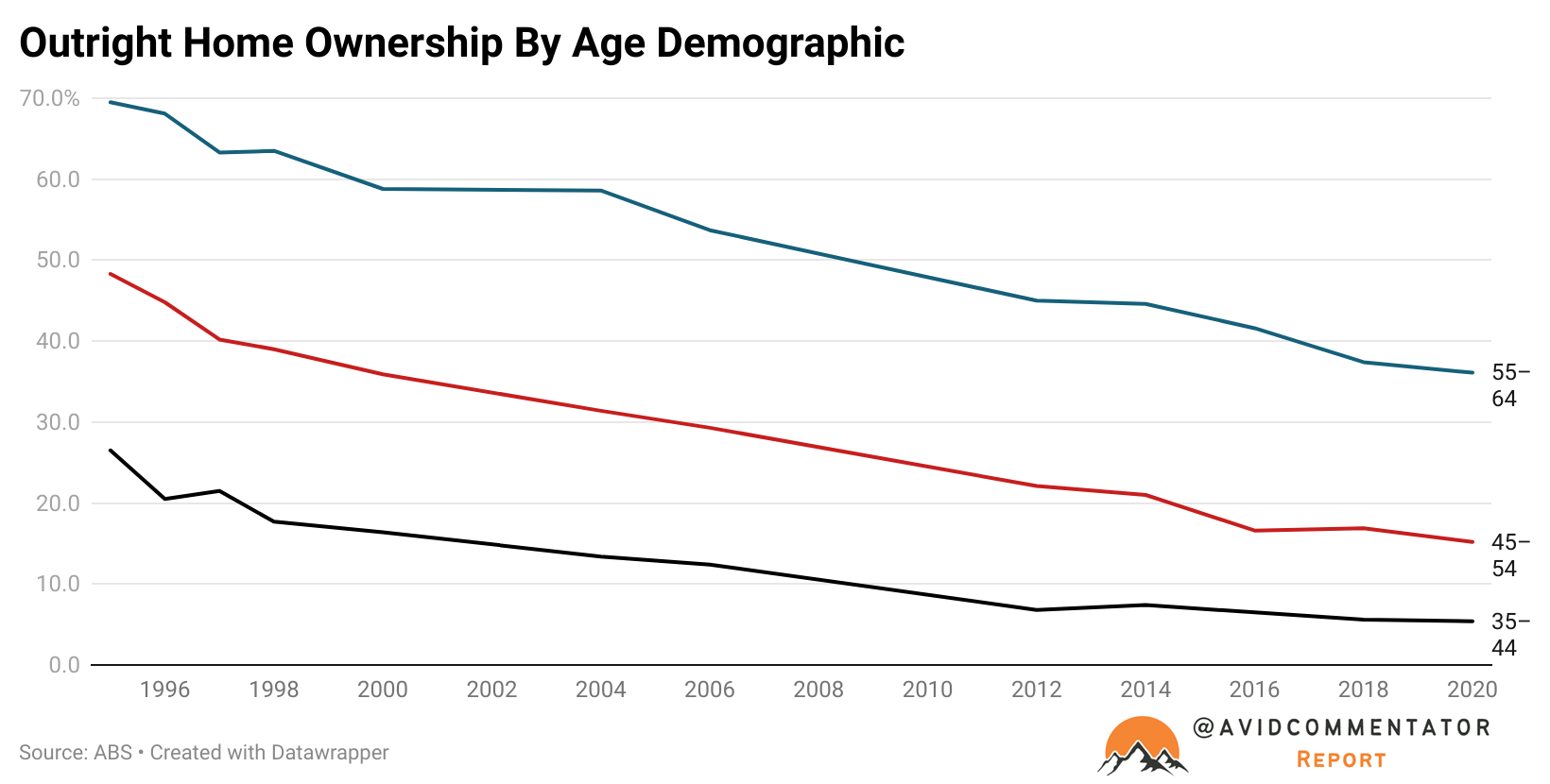

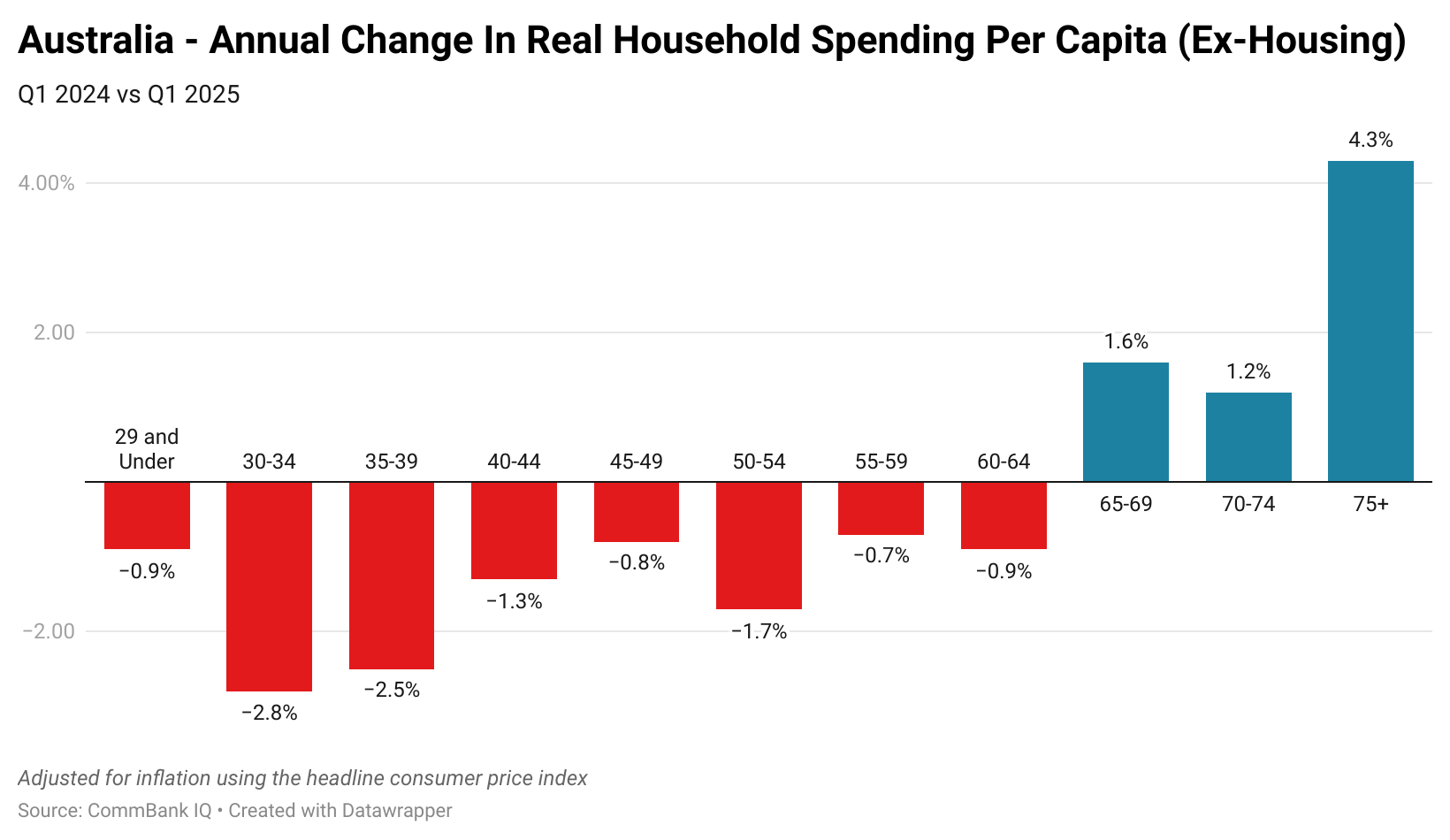

While this issue is often seen as one where the impact is heavily focused on younger demographics, looking at outright rates of home ownership reveals that larger debts and longer mortgages are filtering through across the board.

With outright home ownership plummeting across all under-age demographics under 65, it leaves far fewer households that are debt-free and capable of freely spending before entering their golden years.

On paper, at an average level, they have all manner of wealth, but in terms of accessible capital, that is increasingly outweighed by mortgage debt.

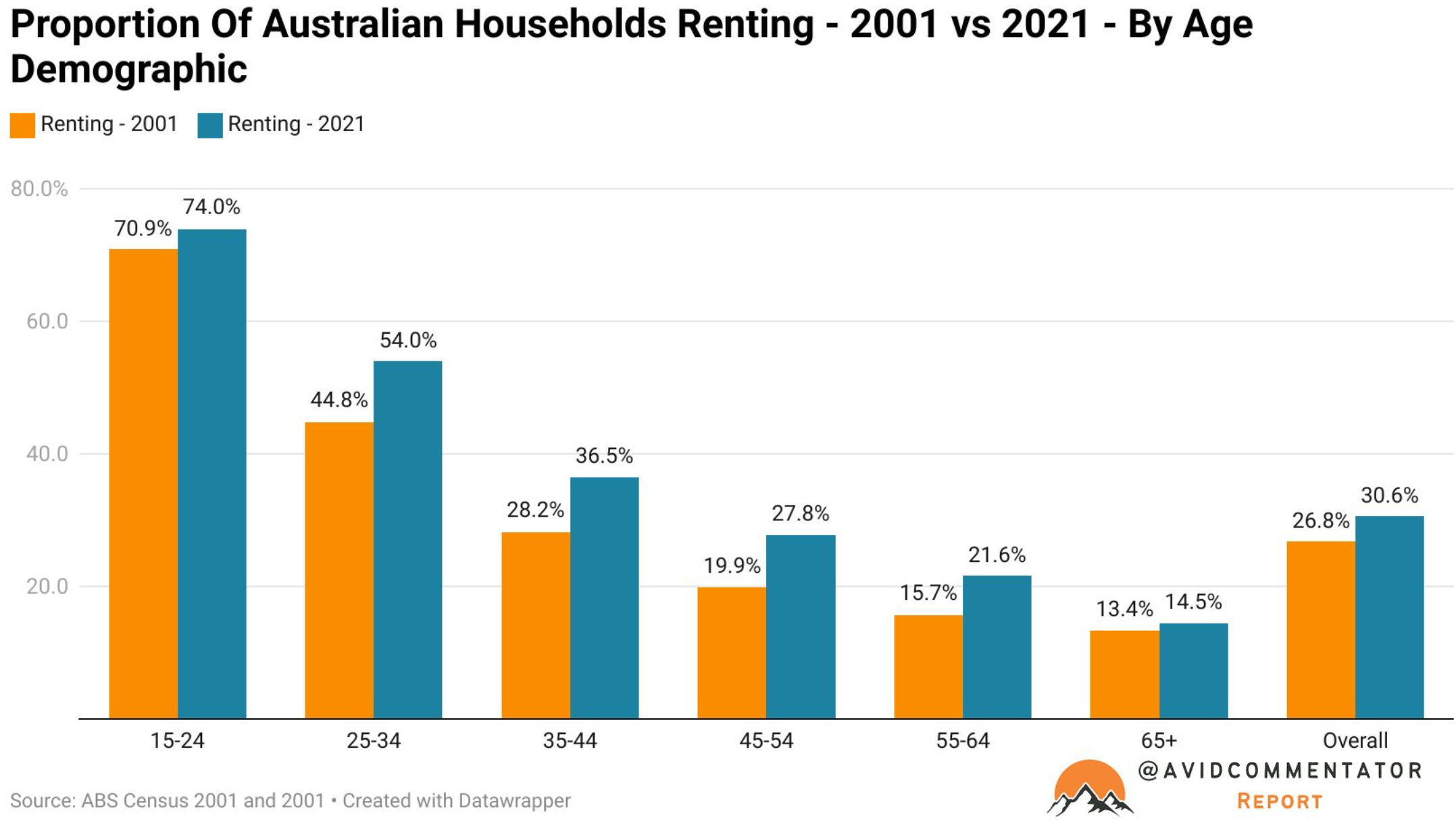

Meanwhile, the proportion of households renting has surged dramatically across most age demographics in the last 20 years.

With fewer homeowners, households are less secure, and they are, on average, less able to build wealth.

According to a 2024 survey from research firm Digital Finance Analytics, around 75% of retirees with mortgages owe more than their superannuation balances.

The pattern is projected to continue as the age of first-time home buyers rises, implying that many will use their superannuation to pay off their mortgages and rely on the age pension.

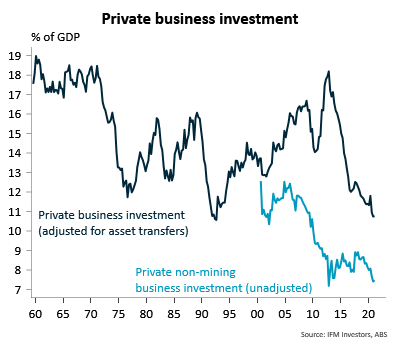

On the other side of the coin, private business investment as a proportion of GDP has collapsed to recession levels and largely stayed there.

Government Takes The Wheel

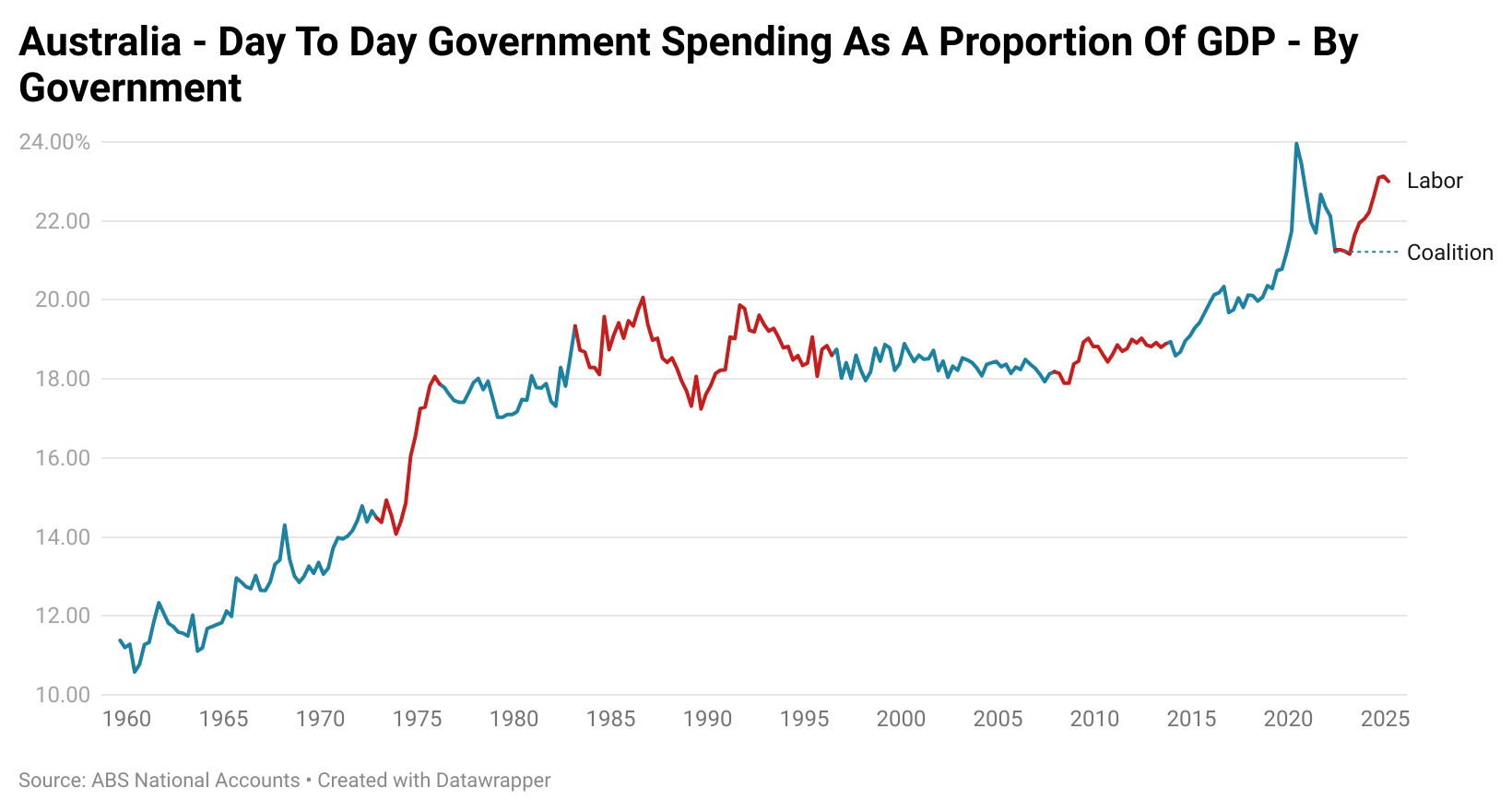

In the years since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), government has taken on an increasingly sizable role in supporting and growing the economy.

While the current level of day-to-day government spending as a proportion of GDP is down from the Covid emergency highs, it remains dramatically above where it was before the pandemic.

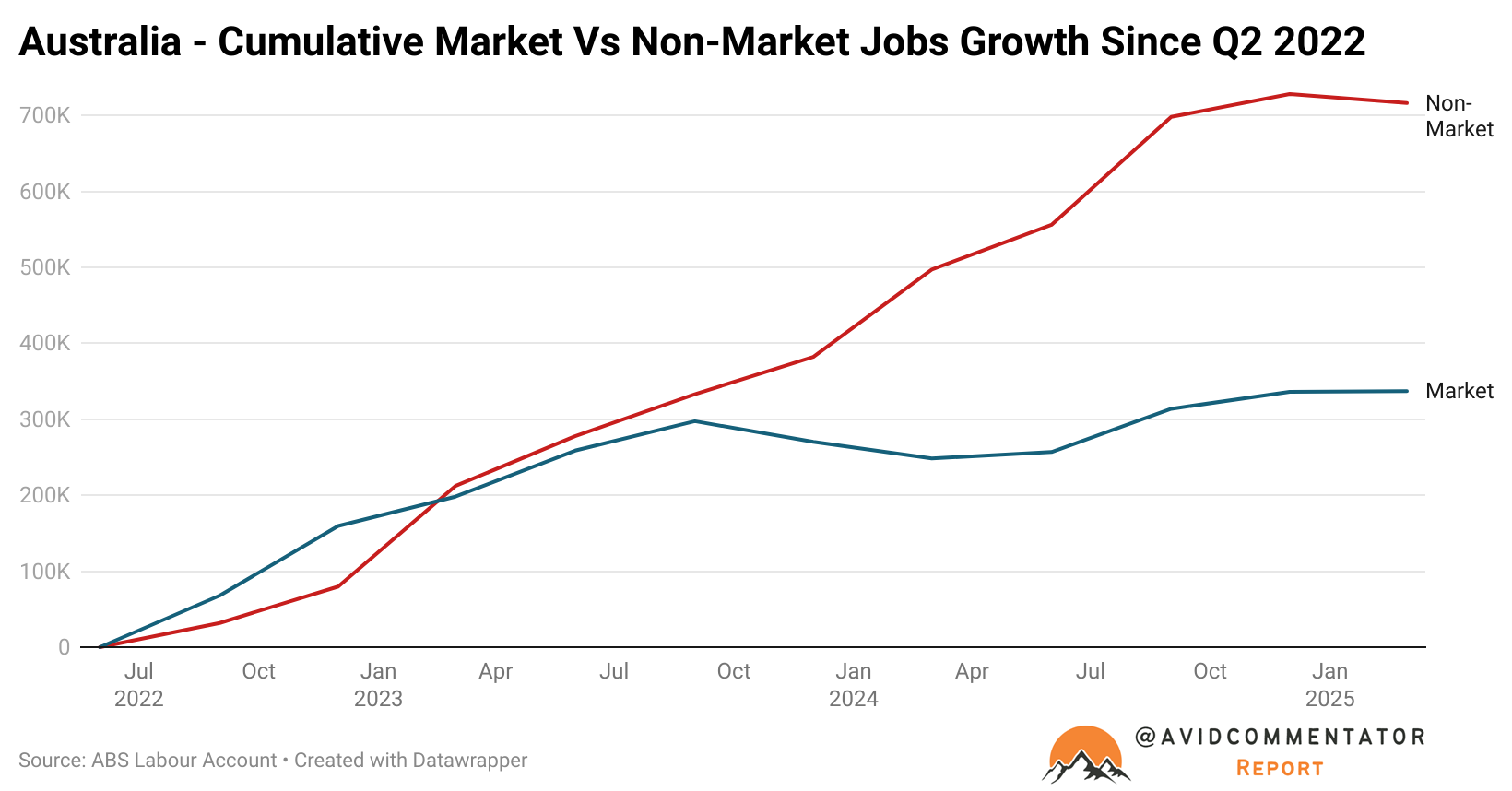

Meanwhile, in the labour market, jobs in industries that are entirely or heavily funded by the government have taken over as the primary driver of employment growth, particularly in the last few years.

Failure To Launch

The Takeaway

In the years since the GFC, the base of the economy delivering growth has become ever narrower.

At an aggregate level, this growing weakness has been papered over by high levels of migration, government spending, and the rise of an increasingly affluent consumer of older demographics.

It is said that the first step in solving any issue is admitting that there is a problem.

Yet the nation’s political class resolutely avoids confronting this challenging reality.