No, Australians should not pay more for energy

Dear Millie Muroi. Greetings from the people of Macrobusiness.

We know you are the young up-and-coming economics commentator in the mainstream media at Nine, and we really do hope that you have a long and distinguished career in Australia’s media.

We understand if the only things you may have heard about Macrobusiness are not all that positive and you have been encouraged to believe that we are generally doom and gloom merchants or toxic in some way—maybe racist, maybe anti-immigrant, maybe ageist, maybe rude about politicians, bureaucrats, some of Australia’s wealthiest people, or even journalists—including some where you work.

To some extent, we regret such perceptions. However, we consider that the truth, or the pursuit and consideration of that which passes for the truth, is so core to our being and so core to the way that we see things that incurring such perceptions for calling what we see as the truth and calling out what we see as untruths by others simply must be done, if only to remind ourselves that we are not alone and that our perceptions have some substance.

That substance we, like you and your fellow journalists at Nine, can place into the public domain and allow others to consider.

In placing those perceptions and considerations into the public domain, we acknowledge that we invite questions about the narratives and data that we use to support our contentions and what we write about.

Indeed, we like people to think about the things we write about so that they can ask questions like we ask questions and they can potentially arrive at better answers than we can derive and let us know! This is the nub, we think we should let you know too!

This, Millie, brings us to the point of today’s post. It is about your article from last Friday week. So let us go there.

Starting with your line of thinking and the data or narrative supporting, you argued:

We should be paying more for our energy. Here’s why

Economics Writer

July 11, 2025 — 5.00am

Millie. It may be unfair to blame you for the headline.

Indeed, it is not out of the question it was written by AI, or maybe someone in marketing as a favour for someone buying advertising space. But it is sitting alongside your name and sometimes in life that brings a perception of responsibility.

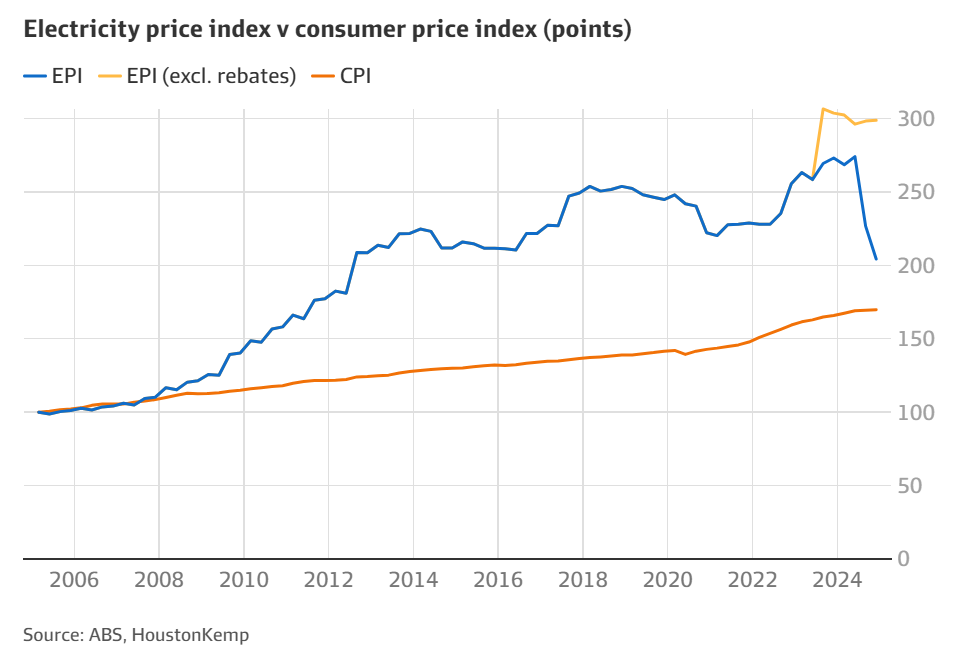

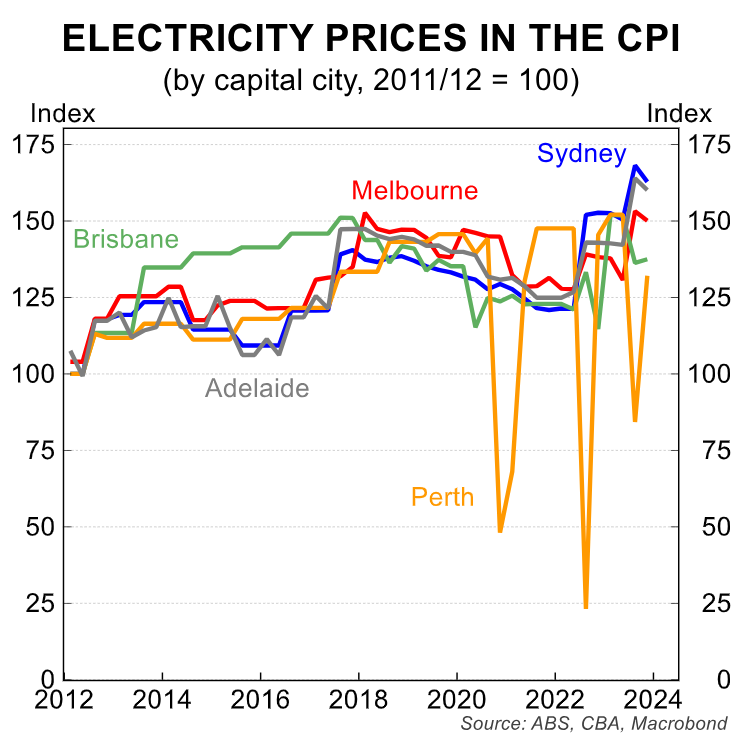

Now at that point we could observe that in Australian society there is a phenomena called a ‘Cost of Living crisis’. While there are a number of contributory factors, any reasonable examination of them brings you quickly to the cost of energy. Energy for turning on lights and cooking or refrigerating food, keeping kids and families warm or cool, and then enabling luxuries like TVs, music, and computers, perhaps.

Those of us at Macrobusiness know some things about energy prices that may not have traversed your thought spectrum. We will get to those. But first, with regard to that headline of your piece, the first thought which lights up is ‘Read the room!’

The reason for that is not such that you need to fear public opinion—which countless surveys and an election indicate is held with some trenchancy by the public on the subject of energy—but, as an editor to a tyro journalist, so you don’t piss off potential readers with the headline.

Use the contents of your skull. If you have a potentially unpopular message, why not try engaging readers with your headline and bringing them with you for a journey of discovery? If you aren’t to convince them of the righteousness of what you posit, can you at least bring them far enough to think they could look at things differently?

Have you done that Millie? Or have you enabled more people to look at that headline and skip past it, sure in the knowledge that Australia’s mainstream media has a chronic credibility issue and is captive to corporate interests that are either Australian and do little but lose money or are global and contribute little meaningful return to Australia for the Australian bounty they exploit?

By the way, take a look at tax payments by Australian gas and electricity producers and compare them with the shareholder returns they declare and where those shareholders are, and compare those with the returns of people receiving electricity bills in Australia.

How much have energy profits for large producers risen? How much have average electricity and gas bills risen?

What do you reckon? And that’s before we get a sentence into what you write!

Let us go back there…….

Do you really think electricity prices should be higher, Millie?

Very few people would agree if I were to say our energy bills should be higher. But what if I told you you’re already paying more than the number you see written on your bills every quarter?

Those relying entirely on renewable energy sources such as the sun to power their homes might think they’re spared. But even the most environmentally conscious among us are paying a higher price than what we see on paper.

OK, the lede. The first sentence is a maybe. But it just underlines the idiocy of the headline. But that second sentence—that too is going to lose people quickly. ‘Already paying more than the number you are seeing written on your bills every quarter’ and then followed with ‘But even the most environmentally conscious among us are paying a higher price than what we see on paper.’ Think about those lines a moment.

Now there will be people thinking ‘I pay what’s on the bill’ and there will be more thinking ‘yeah those service charges are a complete rip off’ and almost everyone will be unified at the point of thinking ‘Nup, I don’t pay any more than what’s on my bill’—and ’they would all be 100% correct. You would have lost some of them there.

If you are going out with an unpopular message, don’t make it vague or specious. Be fair to both yourself and the reader, avoiding dismissing or offending them in the headline.

Confusion is almost as offensive as contempt. Most Australians would rather someone came out and told them they were wrong than tried to bullshit them. What you have done is offend with the headline and bullshit with the lede.

We assume that the point you want to make, Millie, is that the economic cost of providing energy for people to use is greater than the cost factored into their bills. Why not just say that?

Then Rod Sims appears out of nowhere.

Of course, as Rod Sims, former chair of the country’s competition watchdog and Superpower Institute director, said in a speech last month, we couldn’t have gotten where we are without fossil fuels. Coal, oil and gas have helped propel us from city to city, country to country, and even earth to moon. Most of our day-to-day activities would be much harder – if not impossible – without them.

We are like peas in a pod with Rod there. Then Sims gets joined on stage for Millie’s article by Ross Garnaut.

But Sims points out there is no contradiction between enjoying what we have and wanting the world to move away from fossil fuels as fast as possible.

The problem is, humans are generally quite good at procrastinating. Despite the deadline to hit net zero emissions looming closer and clearer, we seem better at ignoring the threat of irreversible climate change than acting on it.

But as economics professor Ross Garnaut puts it, we did not move from the Stone Age because we ran out of stones. We have something to learn from our ancestors’ drive to do things better.

There are a handful of people who still deny the science behind climate change. But there are also plenty of sensible people with reasonable concerns about the best way forward for Australia. Sims outlines several of these worries and why we shouldn’t let them get in our way.

Now at this point Millie lifts the lid on climate change as a concept on the plate. That stanza tells us that climate change means we should be getting right out of fossil fuels, along with Millie’s thoughts about procrastination inclinations of her readers, Garnaut’s thoughts about societal advancement, and Sims noting the desirability of retaining some of the lifestyle and human technology gains enabled by fossil fuels while heading for the fossil fuel exit doors. All perfectly reasonable:-

Millie will take us to ‘But’.

Fundamentally, Millie’s piece shares the same flaw as far too much of Australia’s mainstream business media. It exists in a bubble where things outside the bubble might be disturbing or entertaining but they bear almost no relationship to things happening in Australia.

The only direct linkage in much of the economic commentariat’s minds (and Millie’s it would seem) is that the rest of the world backs their boats up to Australian ports, we load on the national bequest, they sail away, and leave us a tip for being so obliging.

The only other conceivable linkage is the cities full of foreign students who are so thankful and grateful for the chance to get a quality global education in Australia that they don’t mind paying extortionate education fees and packing themselves into rental accommodation, if mum and dad can’t buy them a house here, and will do the menial work ultra cheap to sustain themselves while here.

Much of Australia’s mainstream media thinks there are no downsides to that model. House prices go up, people keep doing whatever it is they do, there are more people to do it for, and there are more restaurants. ‘What is there to not be happy about?’ is their thinking.

Unfortunately, that thinking is a cartoon depiction of Australia and the rest of the world.

Millie now takes us into just how crazy this thinking is.

First, the concern that the rest of the world is not moving to net zero, so Australia taking action is pointless.

But just because everyone else is sleepwalking towards a cliff, it doesn’t mean we should follow. In fact, it’s a good time to walk in another direction. It’s also a myth to say no one else is trying or that we’re all lacking in ambition.

As Sims points out, we often hear about China building coal-fired and nuclear electricity generation facilities at a mind-boggling scale. But last year, about 80 per cent of China’s 429 gigawatts of new electricity-generating capacity (roughly enough to power 322 million homes) was solar and wind powered.

And the European Union has had enough appetite (or perhaps courage) to introduce a price on carbon.

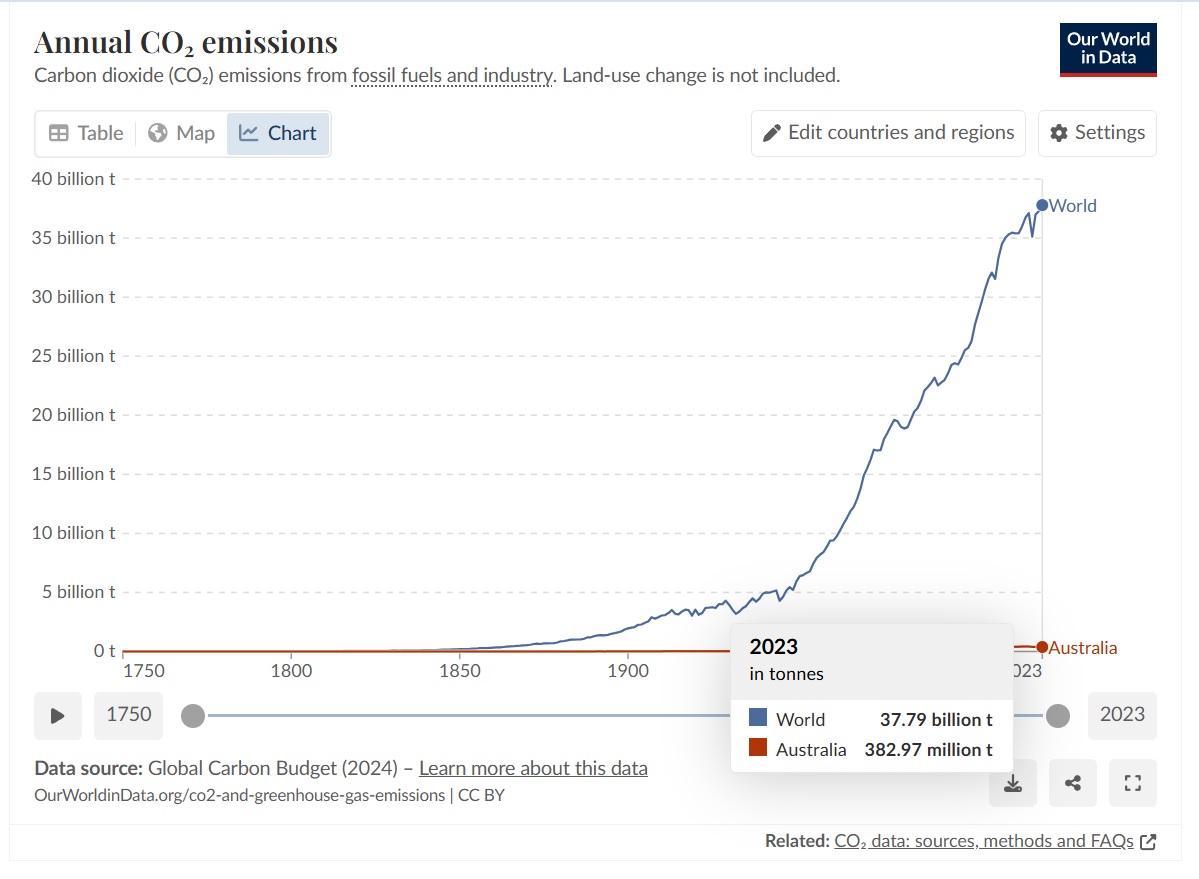

Second, some people claim Australia only accounts for about 1 per cent of world emissions, so it doesn’t matter what we do.

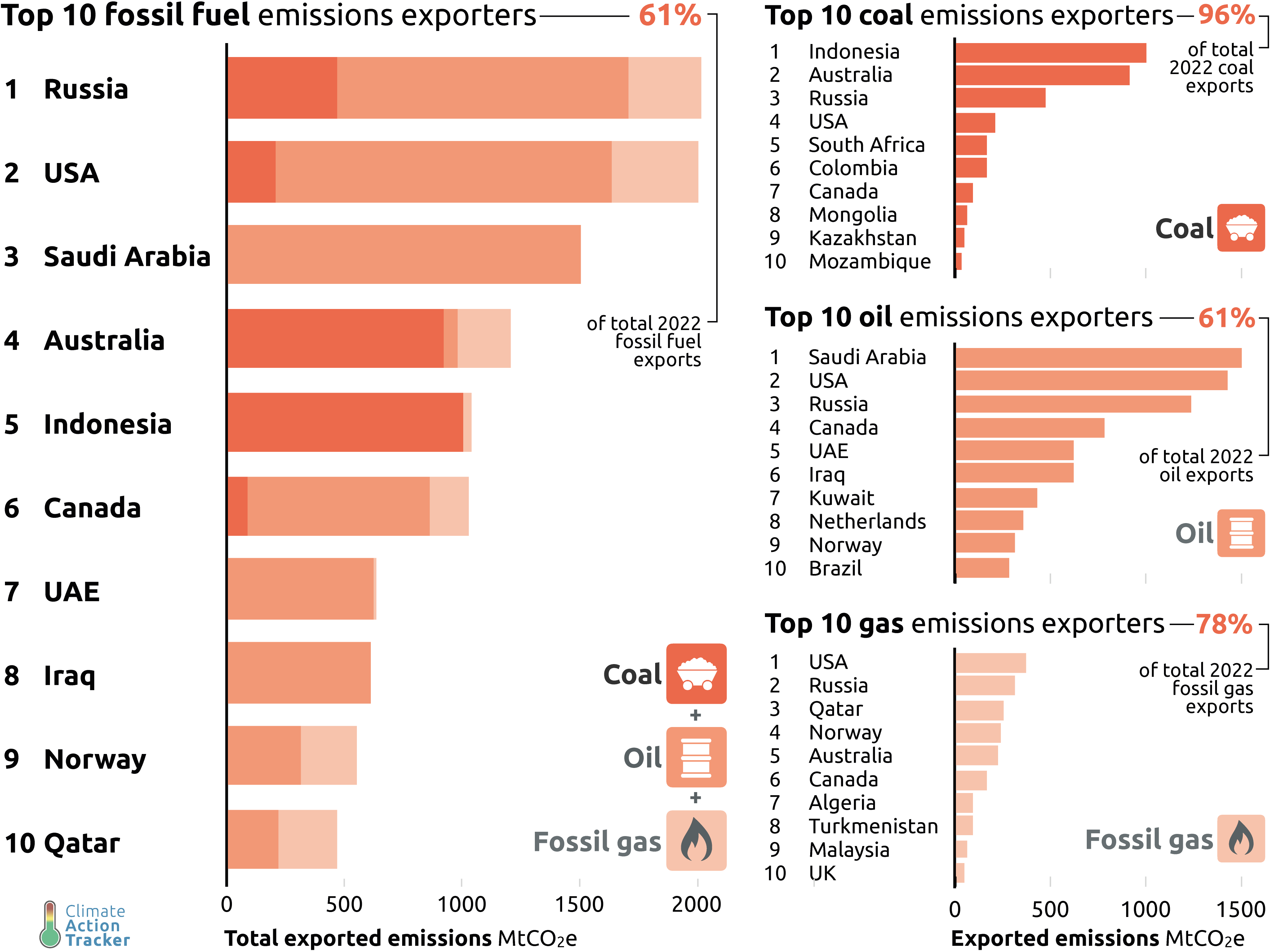

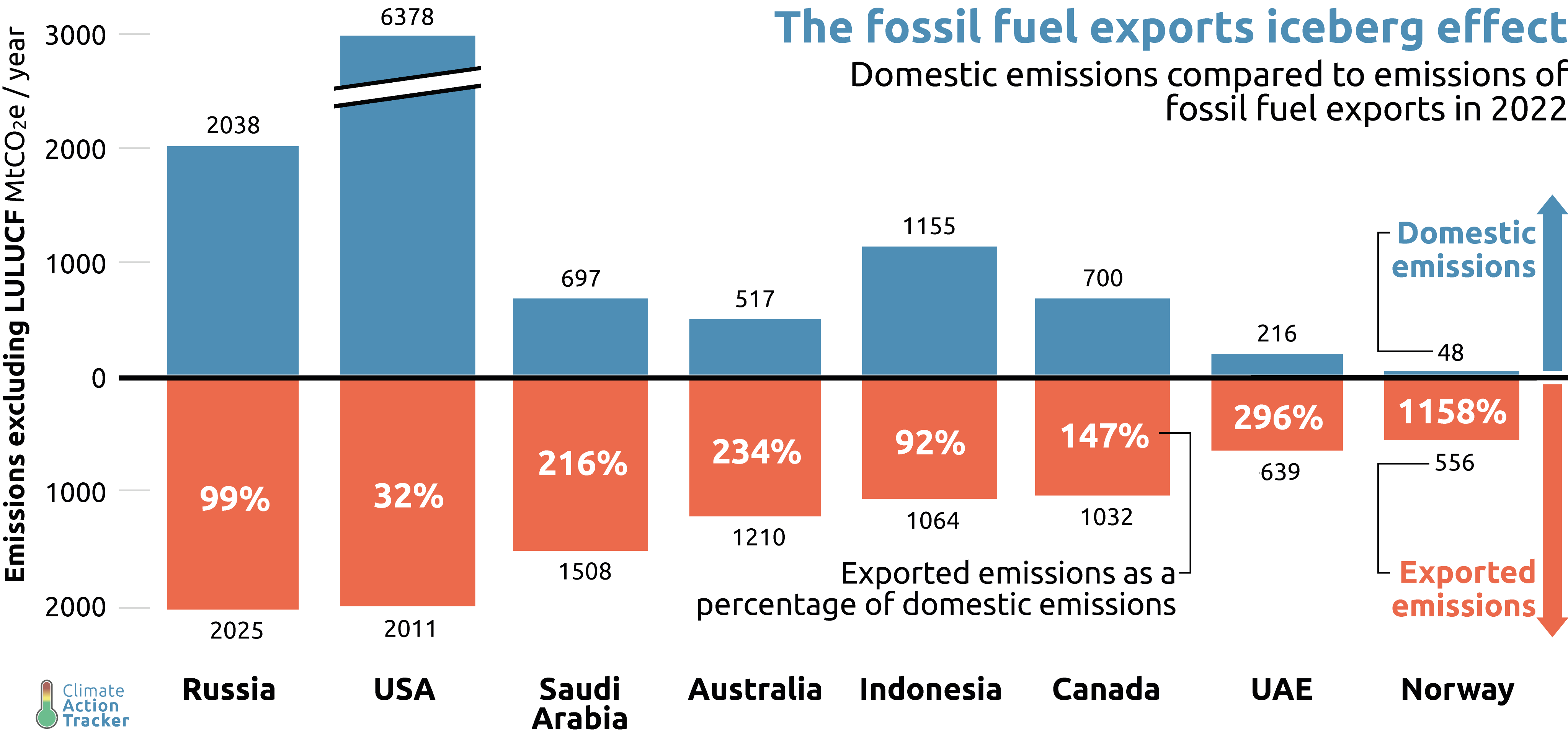

The clear moral argument is that we should still play our part. But Sims also points out that when we include exports (Australia is the biggest supplier of coal and gas combined in the world), our contribution to emission is more than three times higher.

The world (blue line) may certainly be walking off the cliff but Australia (brown line) isn’t going to make a material difference

…..unless Australia bans energy exports

Millie now introduces the rest of the world. It is sleepwalking towards a cliff and Australia should walk the other way. At that point two fundamental questions arise.

The first is:

“Should, if we walk the other way, walk with such effort and intensity as to cause pain in our own society if the rest of the world walking off the cliff will take us with it no matter what we do?”

The second is:

“Seeing as Australia is a massive energy exporter—see coal and gas exports—and the rest of the world is using this energy export to power itself walking off a cliff, would Australia do more for preventing the world walking off a cliff if it were to itself achieve net zero, or if it simply ended all of it’s energy exports to the rest of the world?”

Another way of looking at that same dynamic would be to simply pose the question:

‘Should Australian energy bill payers wear the pain for trying to prevent the world walking off a cliff, or would it make more sense for Australian gas and coal exporters to wear the pain through a levy or cessation of their exports?’

We could observe that Australian bill payers at least live here, work here, and pay taxes here. We bump into Australian energy bill payers every time we line up to check out at Coles or Woolworths, get into a crowded train or bus, or mix with the others at the local football or netball club.

We work with them, we have a beer with them, we go to church with them and they listen to much the same music as we do. They are us. We are them. Not always the most sophisticated or cultured, but often robust with humour and amongst the world’s more reasonable peoples.

Exporters of Australian energy, on the other hand, are the scions of global capital elite—the 1%—who go to extraordinary lengths to avoid paying taxes to benefit Australia and will be gone the day the reserves they export are gone.

What do you think, Millie? Anyone else at Nine? Anyone anywhere else in the mainstream media?

That 8o% of new renewable energy China installed last year—how does that compare with Australian energy exports to China?

That carbon tax the EU has implemented—are any Australian producers of goods affected by that or is the impact on Australia greater through the effect on nations using Australian raw materials or energy? If the latter, should we be toning down carbon-generating exports?

And Millie, if the rest of the world doesn’t follow the EU model, does that mean we should ease off inflicting pain on ourselves and prepare ourselves for the post-cliff world?

Right at the end there, Millie steps on something known as ‘morality’ which is another core failing of much of Australia’s mainstream media. Millie’s moral assumption here is that Australian bill payers—her readers—should bear the pain of carbon adjustment rather than bill payers in the rest of the world or large corporate interests in Australia (where they don’t bear much pain anyway, and they profit from the pain not being paid by the consumers elsewhere and use Australia’s polity and media to obscure their involvement in the pain Australia’s energy consumers wear). No thanks, Millie.

The enormity of that moral position is that Australia’s polity, Australia’s bureaucracy, Australia’s capital owners and their managers, and Australia’s mainstream media—by and large—are united by it.

Millie proceeds into fairy tale territory:

From an economic perspective, we’re also throwing away what’s called our “comparative advantage”. That is, because of our nearly bottomless supply of solar and wind, and our relatively small population, we’re actually able to generate clean energy at a lower cost than most other countries – and sacrifice far less in terms of other things we could be doing with our time and resources.

Countries such as China, Japan, South Korea and India face a growing shortage of low-cost green energy to run their economies, meaning there’s a big opportunity for Australia to step in as a supplier.

But Australia also has a chance to step up as a maker and exporter of goods such as iron and steel.

Right now, despite Australia having the ingredients – huge amounts of iron ore, the coking coal needed to turn the iron ore into iron (the metal), and the thermal coal and gas to power the whole process – most of our iron ore is shipped out to, and turned into iron and steel in, north-east Asia.

That’s because all these ingredients are fairly cheap to ship and north-east Asia can produce things at a scale – and therefore low cost – we can’t match.

But as green iron becomes more crucial in the quest for a net zero world, the costs of producing the stuff will change.

The renewable energy needed to create green hydrogen (the replacement for coking coal), and to power the process (instead of thermal coal) are expensive to export – as is green hydrogen. Sims notes exporting coking coal only adds about 10 per cent to the cost of producing iron, while exporting hydrogen instead would just about double the cost.

Rather than sending off all the ingredients, Australians could (and it will make more sense to) make the entire green product here ourselves. What we do now to build this capability will matter hugely – for ourselves, and for the world. By some estimates, Australia producing intensive green exports could slash world emissions by up to 10 per cent.

Millie, our current comparative advantage is the availability of cheap energy through our current coal and gas reserves. We are throwing that away by degrading our ability to burn the coal and sucking all of our gas out of the East Coast to give to the rest of the world at loss leader prices and subsequently looking at buying it back at global spot market prices.

Our comparative advantage is comparative stupidity as far as much of the rest of the world is concerned. They bank on us sacrificing our comparative advantage to please them.

If we treat our future comparative advantage as we treat our current competitive advantage then we could consider paying the rest of the world to fellate their balance sheets. Is that what we want for tomorrow’s Australians?

What Millie posits about wind and solar sounds great. But Australia has been trying to do more sophisticated stuff for about 200 years and has failed abysmally.

Millie seems oblivious to the idea that much of the rest of the world has wind and solar potential. They bump into much the same storage and transmission issues Australia does.

Given the same applies for the generation and transmission of hydrogen energy, there would be a case for placing money on somewhere other than Australia getting it right.

Given Australia’s repeated failures to develop economic resilience and substance without selling out down the track, would you bank on someone somewhere else doing things via solar, wind, water, or hydrogen, or any green power really, or would you invest in someone in Australia doing it? And if someone in Australia did do it, would their concern be Australians at that point or a global market?

Sure, Australia could make ‘green’ steel or metals or even metal products down the track somewhere. But right here, right now, in 2025, Millie is talking about the exploitation of child labour in the Congo, toxic minerals processing in China, and shiploads more imports for the world’s most expensive people on the world’s most expensive land using the world’s most expensive energy and internet to do things the rest of the world doesn’t want, all tied in with the world’s most outrageous energy bills. And the stupidity of Australian energy policy is central to that. Millie is supporting the most pernicious impacts of that for ordinary Australians.

Let us return to her.

Third, some people ask why Australia can’t use nuclear energy or carbon capture and storage rather than renewables such as solar and wind power.

The Liberal Party’s resounding defeat, while not purely down to their nuclear policy, was a sign the political appetite is just not there for nuclear. But nuclear and carbon-capture techniques are also very costly.

“Of all the nuclear plants built since 2000 in countries such as the USA, the UK and France, projects have been much delayed and costs have around tripled those first estimated,” Sims points out. “Nuclear energy costs are now three to five times that of firmed renewable energy.”

The possible exceptions to this trend – South Korea and China – have more opaque costings for nuclear and have been helped along by heavy government subsidies.

While carbon-capture costs haven’t yet fallen enough to be a realistic option in most circumstances, and nuclear costs have continued rising, the cost of solar, wind and batteries has fallen rapidly. Solar power in particular could, over the next decade, offer electricity at half the cost of the cheapest available today.

Millie returns with more whataboutism. Sure, Australians don’t like the idea of nuclear. There has never been a need for it in Australia’s past because we have and had abundant cheap energy. It is expensive to build from scratch, and it is the same stuff used to make nuclear weapons.

But Australia does have large uranium resources, and Australia does have geologically stable locations to build such facilities. If the transition need is so profound as to traumatise Australians through their energy bills, then couldn’t it be the reliable base load to replace our coal-fired stations, built astride our existing transmission systems?

Is green solar and wind really cheaper? Is it reliable enough without building at scale multiples larger than what we have to cover for the risk of the cloudy day, windless days, or night? Then there are the questions about toxic solar materials processed in China and the child labour in the Congo, or the lifespan and replacement costs of solar or wind generation capacity and storage. Are they considerations? Renewables are also heavily subsidised.

Should there be considerations before inflicting bill pain on the people in the streets here?

Sure, we get the idea that the costs of global warming, which most of us accept is caused by human activity and particularly fossil fuel use, will embed major mitigation costs. But what about the costs of mitigation in comparison with the costs of our current transition trajectory?

Sure, we get the general idea that carbon sequestration is not meaningfully going to happen and will be humungously expensive. But what about a consideration of pros and cons comparison rather than the ‘stop it or you will go blind’ thinking we are served up as a fait accompli every day?

Millie is back with more.

The fourth issue people raise is that green products are expensive. But that is only if you ignore the cost of climate change. The harm to our environment and the possibly irreversible change to our planet are costs that are not reflected in the price we pay for products and energy generated using fossil fuels.

People living in floodplains and farmers facing longer and worse droughts might see these costs most directly, but many of us don’t see it in our everyday lives.

Putting a price on carbon helps to capture this cost. It might drive up the price of some of our goods and services – especially over the short term – but it helps reflect the full consequences and guides businesses and customers to push for cleaner alternatives.

The government providing subsidies – such as payments or grants – to generators of renewable energy and makers of green products could also achieve a similar aim.

Yes, green products are expensive. They are competing with products fuelled by fossil and the vast bulk of buyers only concern themselves with the price on the invoice.

The climate isn’t issuing invoices yet and when it does, could we assume there will be some good with the bad? Or is it all bad? And if it is all bad, wouldn’t that open up an opportunity and market for someone to cash in on? Isn’t that how capitalism works?

As for Millie’s thoughts about carbon prices and their short-term price impacts, what is she saying? Should we cease flying or boating in Danish ham, foreign wines, and Kiwi kiwifruit, and kids toys from China and tell someone to make them here? In a nation importing just about everything used in daily life, would our position vis-à-vis global warming get a boost from ending imports? Millie, is that what you are saying?

If we are about placing a price on carbon, shouldn’t that price be for all customers, starting with the biggest customers, which happen to be foreign buyers in the case of Australian gas?

And that throwaway line about subsidies, Millie. Would that lead to new products or would global capital simply turn those into a teat to extract some more from Australian taxpayers?

And for a conclusion, we are back to not recognising where we are.

Just as gas and minerals have played a huge role in Australia’s economic development, so can exporting green energy-intensive goods. Research by the Superpower Institute’s research lead Reuben Finighan shows the potential export revenue from these goods could amount to roughly the same size as all Australia’s current exports put together, and six to eight times larger than the country’s combined coal and liquefied natural gas export revenue.

That’s if we invest about 5 per cent of our economic output – or gross domestic product – every year for the next few decades. It’s another bill to foot, but as Sims points out, about the same level of investment as when Australia leapt on the Chinese minerals boom two decades ago. We’ve done it before so we can do it again.

Millie, the gas and minerals are great, but they aren’t the society you see around you. They aren’t your readers. Your readers and the society around you exist inside a bubble enabled by those minerals and gas. That’s great too, but the risk is that prices spike or collapse or the commodity ends and then the society around you has to have another strength.

Economists will tell you that any economy is best when it is using the people in it to do something productive—meaning it produces a good or service that the rest of the world wants, or it produces the same for Australians, which replaces a good or service otherwise imported from the rest of the world. Your current Australian society isn’t going within a bull’s roar of doing that.

Then on top of that, especially if you remember the resources providing our lifestyle are finite, your current Australian society is importing people at a globally unheard-of rate to distribute the largesse enabled by those resources ever more thinly—but that’s a subject for another day.

The real next issue arising from your piece is that Australia has been trying to move on from being a quarry or feedlot for more than 200 years and has never done it. In that time, it has sold itself all sorts of narratives about where it is going—the latest is green energy hub, and the thinking espoused by Rod Sims and Ross Garnaut.

Rueben Finighan’s very good research for the Superpower Institute says Australia ‘could’ create a market. Certainly it could. But numerous others regularly note Australia is unlikely to – for reasons ranging from labour costs to distance from key markets.

In the Houses and Holes economy we have in 2025, maybe we could have articles about parallel universe rainbows up the backside we could export as well.

…….and that brings us to another concern with your piece Millie. And that is your journalistic values.

Millie, your article only refers to one single external source, a speech by Rod Sims to a private function on 26 June 2025. Your article is headlined ‘We should be paying more for our gas. Here’s why.’

How many times in that speech did Rod Sims refer to gas bills we should be paying?

None.

Now the perception at this point is that you probably didn’t even attend to the speech by Sims; you just quoted slabs of his speech about myths surrounding the green energy transition—all of which have some substance, but all of which raise questions—to extrapolate that Australian consumer energy prices need to go up.

It would have been a far greater service to your readers to ask Sims or Garnaut what they thought needed to happen with Australian energy costs or to see if Sims thought ending gas exports and having cheap energy in Australia was a worthwhile idea?

But to pass them off as somehow supporting the contention that Australian energy bills needed to go up off the back of the Sims speech probably isn’t where journalism needs to be, or is it?